In the fall of 2024, Pomona launched a minor in data science. To commemorate the new concentration, let’s look back at some of the College’s milestones in computer science and technology.

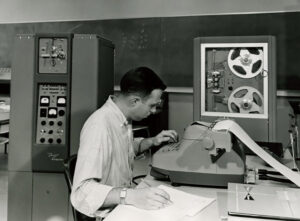

1958: Five years after first offering “computer classes” for word processing, Pomona opens Millikan Laboratory, its first computer lab, which included a Heathkit analog computer and the Bendix G-15 digital computer. One of about 400 manufactured globally, the Bendix was the size of a refrigerator, required punched paper tape to load instructions and data, and had “memory” in the form of a rotating drum the size of a wastebasket.

1964: As part of the launch of the Seaver North science building, Pomona is one of the first U.S. schools to buy an IBM System/360 computer, which eager Assembly- and Fortran-learning undergrads used for work in chemistry, economics, geology and math. The Student Life newspaper marveled at how a unit the size of a cigar box could contain the computer’s entire memory of 16,000 bytes; today’s smartphones are roughly 16,000,000 times more robust.

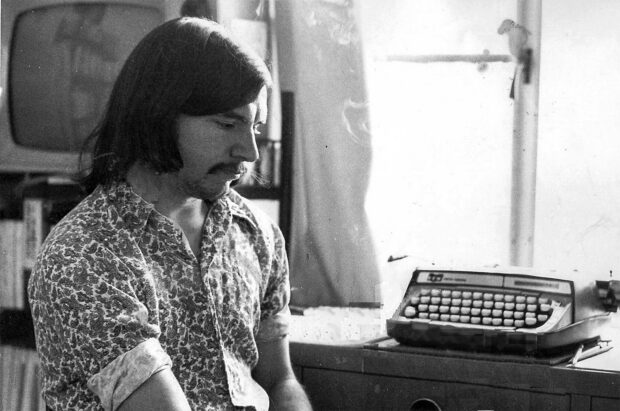

1971: The Mudd-Blaisdell residence hall is outfitted with a PDP-10 mainframe, immediately sparking the interest of first-year Don Daglow ’74, who used the computer to create several early video games, including what’s widely regarded as the world’s first “role-playing game,” which was a text-based game adapted from the then-new “Dungeons & Dragons” tabletop game.

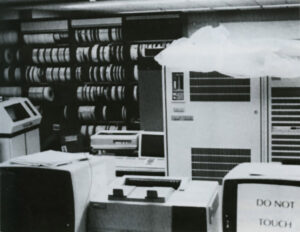

1980: Five years after purchasing IBM’s second-ever 5100 minicomputer, Pomona becomes the first educational institution to own and operate an IBM 4331, which opened students up to being able to use email.

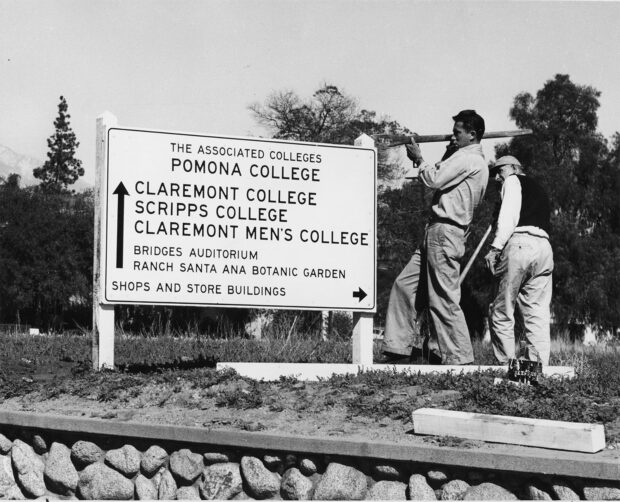

1988: The Mudd Science Library installs a VAX 6310, which permits the linking of computers to the other 5Cs, thereby introducing students to resources such as the internet. That same year Pomona and several other schools launched the Science, Technology and Society program.

1991: The first two computer science majors graduate from Pomona. Computer science split off from math to become a separate department in 2006, and is now one of the College’s most popular majors.

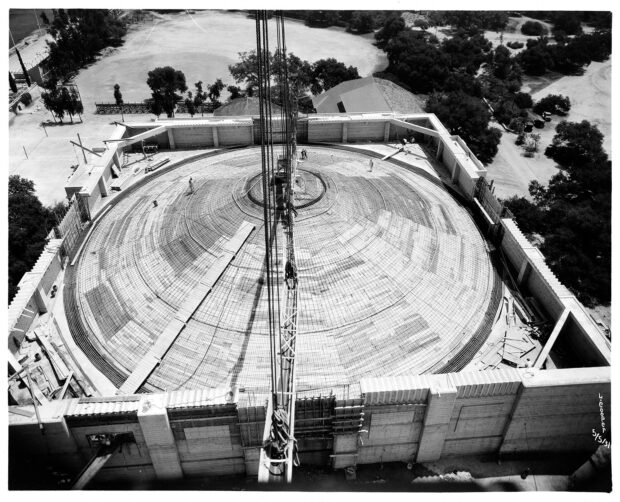

2000: Pomona launches the Andrew Science Hall for Mathematics, Physics and Computer Science—the first time there was a dedicated space for computer science as an academic discipline. By 1997, Pomona also had become one of the first colleges to hook up every single bedroom in its dormitories to a 56K network connection for internet use.

2014: Pomona is named the country’s “most wired college” by the higher-education review platform Unigo, which previously cited Pomona’s innovation in being one of the country’s first colleges to provide Wi-Fi connectivity to all of its dorms.

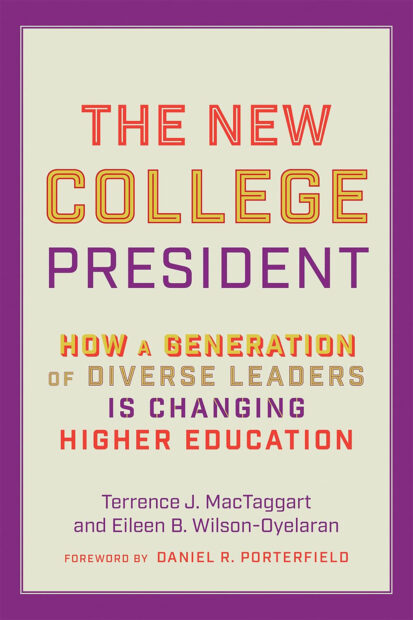

The book, “The New College President: How a Generation of Diverse Leaders Is Changing Higher Education,” co-written with Terrence MacTaggart and published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, profiles seven university leaders and describes the skills and personal qualities they possess that have made them successful.

The book, “The New College President: How a Generation of Diverse Leaders Is Changing Higher Education,” co-written with Terrence MacTaggart and published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, profiles seven university leaders and describes the skills and personal qualities they possess that have made them successful. During her years at Pomona, Wilson-Oyelaran was a galvanizing figure who was instrumental in creating The Claremont Colleges’ first Black Student Union in 1967 and the Black Studies Center in 1969. She says that she’s deeply encouraged by how her generation’s efforts transformed higher education, both in terms of what the student body looks like, and in the expanded breadth of the curriculum.

During her years at Pomona, Wilson-Oyelaran was a galvanizing figure who was instrumental in creating The Claremont Colleges’ first Black Student Union in 1967 and the Black Studies Center in 1969. She says that she’s deeply encouraged by how her generation’s efforts transformed higher education, both in terms of what the student body looks like, and in the expanded breadth of the curriculum. Los escritores y el flamenco. La lucha antifranquista (1967-1978)

Los escritores y el flamenco. La lucha antifranquista (1967-1978) I Am We

I Am We Disaster Nationalism

Disaster Nationalism The New Rules of Influence

The New Rules of Influence Hidden Healers

Hidden Healers Abigail and Alexa Save the Wedding

Abigail and Alexa Save the Wedding Animating the Victorians

Animating the Victorians I Trust Her Completely

I Trust Her Completely Deadly Vision

Deadly Vision

Moon

Moon

Night

Night