When Amy Watt ’20 got the call that she would be traveling to Rio de Janeiro in early September, her joy in making the U.S. Paralympic track and field team was tempered by worry about missing the first two weeks or so of her first semester at Pomona. She remembers calling Pomona-Pitzer Women’s Cross-Country and Track & Field Coach Kirk Reynolds with trepidation.

When Amy Watt ’20 got the call that she would be traveling to Rio de Janeiro in early September, her joy in making the U.S. Paralympic track and field team was tempered by worry about missing the first two weeks or so of her first semester at Pomona. She remembers calling Pomona-Pitzer Women’s Cross-Country and Track & Field Coach Kirk Reynolds with trepidation.

“I didn’t know who I should contact or what to do about missing some school,” recalls Watt. “He just asked when I’d be gone, information about the events, and the dates for everything. He talked to several people and the dean; he took care of a lot of it for me and made it easier for me.”

Born without part of her left arm, Watt has been an athlete since discovering soccer in kindergarten. She continued playing the sport until she fell in love with track and field in junior high school. “I was encouraged by my mom and friends,” says Watt. “It was also a fun activity to do.”

Her path from there to the Paralympics involved a couple of chance encounters and an aha moment concerning the rules.

One day during track practice at Gunn High School in Palo Alto, when Watt was in the 10th grade, a Gunn alumnus who is an amputee recommended that she check out the 2014 U.S. Paralympics Track and Field National Championships, being held in nearby San Mateo.

There she happened onto an amputee friend who was competing in a 4×100-meter relay. By chance, the group needed one more person. Watt agreed to fill in and was immediately hooked.

“Never thought I could do Paralympic track and field until I saw some other arm amputees and realized I could also do it,” says Watt, who had always assumed that those competitions were meant for leg amputees. What she discovered was that the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) has a classification system that determines athletes’ eligibility and divides them into sport classes with athletes with similar impairments. The category in which she was eligible was one that seems perfect for a Pomona-bound athlete—IBC classification T47.

Soon she was competing at the international level, traveling to the Netherlands for the International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation World Junior Games and then to Toronto for the Parapan American Games, where she took fourth place in the 100- and 200-meter events. Last year, as a high school senior, Watt traveled to Doha, Qatar, where she participated in the IPC World Championships and came in fifth in the 400-meter dash and seventh in the long jump.

Between homework and world competitions, Watt had a tough decision to think about: college. Having decided she wanted to attend a Division III school, she got in touch with track and field coaches from her top choices.

When she visited Pomona, she was struck by the people she met and the tight community. “I liked that family feel before you get to campus. I liked having small classes; that’s something I really wanted in any school. I liked the general feeling on campus and could envision myself here being really happy. I met a lot of intelligent but humble people here.”

In Rio, Watt competed in three events—the long jump, in which she finished sixth; the 100 meters, in which she made it to the semifinals; and the 400 meters, in which she also finished sixth.

“Even though I didn’t perform as well as I had hoped in my events, the overall experience I had was incredible,” she says. “Now that I’m back, I’m catching up on a few assignments and other classwork that I missed, and all my professors have been understanding and supportive. I was touched that many of my classmates have congratulated me on my performance and watched some of my races.”

Although she’s not sure what she plans to major in, she is sure she’s going to continue track and field at Pomona.

“She is a remarkable jumper and sprinter who has had a successful high school career, and I know she can continue to improve her performance in all her events,” says Reynolds.

And though the next Paralympics won’t happen until her senior year is over, she can’t help thinking about it sometimes.

“Sometimes I still have a hard time grasping that I went and competed in the Paralympics,” she says. “It was such an unforgettable experience to be running with the best athletes in the world. I would love to go to Tokyo in 2020, but I’ll need to keep working hard to get better and perform well at trials.”

“There is no bad opportunity. There is no wasted effort. There is no wrong turn. Your worst day, when the boyfriend or the girlfriend leaves you, and your parents don’t believe in you, and the teachers flunk you out of a course, and you don’t have enough money to pay for the semester, and you have that sick, horrible feeling in your gut of disaster and failure and no self-worth—you’re gonna use the crap outta that one day. So sit with it, suck it in, enjoy it and go, ‘Yeah, this is gonna be so good 10 years from now.’”

“There is no bad opportunity. There is no wasted effort. There is no wrong turn. Your worst day, when the boyfriend or the girlfriend leaves you, and your parents don’t believe in you, and the teachers flunk you out of a course, and you don’t have enough money to pay for the semester, and you have that sick, horrible feeling in your gut of disaster and failure and no self-worth—you’re gonna use the crap outta that one day. So sit with it, suck it in, enjoy it and go, ‘Yeah, this is gonna be so good 10 years from now.’”

When Amy Watt ’20 got the call that she would be traveling to Rio de Janeiro in early September, her joy in making the U.S. Paralympic track and field team was tempered by worry about missing the first two weeks or so of her first semester at Pomona. She remembers calling Pomona-Pitzer Women’s Cross-Country and Track & Field Coach Kirk Reynolds with trepidation.

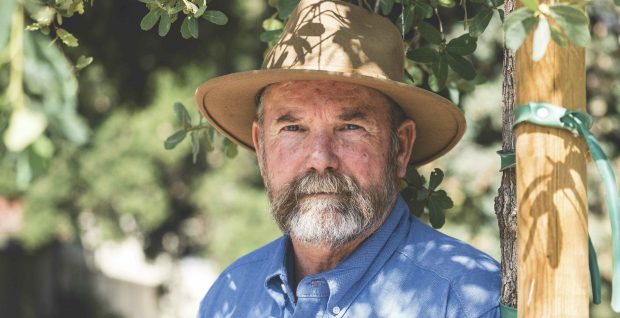

When Amy Watt ’20 got the call that she would be traveling to Rio de Janeiro in early September, her joy in making the U.S. Paralympic track and field team was tempered by worry about missing the first two weeks or so of her first semester at Pomona. She remembers calling Pomona-Pitzer Women’s Cross-Country and Track & Field Coach Kirk Reynolds with trepidation. This is not how most of us think of Pomona’s third and perhaps best known president, James A. Blaisdell, but like the rest of us, he was once a child, and unlike most of us, he had his likeness recorded at the age of about six in the form of a plaster bust.

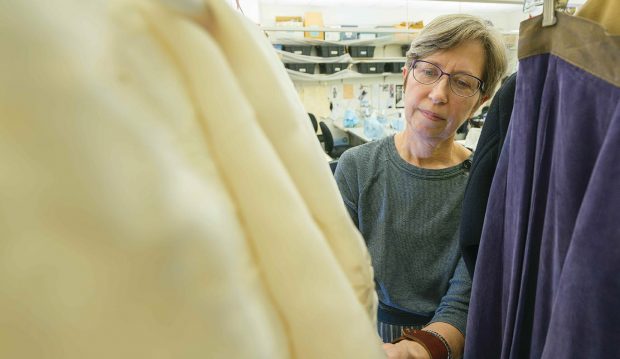

This is not how most of us think of Pomona’s third and perhaps best known president, James A. Blaisdell, but like the rest of us, he was once a child, and unlike most of us, he had his likeness recorded at the age of about six in the form of a plaster bust. Suzanne Schultz Reed’s classroom is not your typical seminar room. Upon entering, visitors are immediately greeted by a costume rack boasting dozens of hangers and garments in various states of completion. Long project tables dominate the open space, ringed by smaller workstations furnished with bright white sewing machines and strips of fabric. The walls are covered in color sketches of period dresses and men’s breeches; visible in the supply cabinets are buckets of buttons and thread and pincushions. Today is Wednesday and the room is uncharacteristically quiet, humming only with the sound of sewing machines and soft conversation between Schultz Reed and her student worker, Amy Griffin (Scripps ’18). “On Fridays, I have six students working in the shop,” Schultz Reed explains. “It’s very social. Everybody’s chatting, everybody’s doing something, music is on. And—” here she grins wickedly—“I bring brownies on Fridays.”

Suzanne Schultz Reed’s classroom is not your typical seminar room. Upon entering, visitors are immediately greeted by a costume rack boasting dozens of hangers and garments in various states of completion. Long project tables dominate the open space, ringed by smaller workstations furnished with bright white sewing machines and strips of fabric. The walls are covered in color sketches of period dresses and men’s breeches; visible in the supply cabinets are buckets of buttons and thread and pincushions. Today is Wednesday and the room is uncharacteristically quiet, humming only with the sound of sewing machines and soft conversation between Schultz Reed and her student worker, Amy Griffin (Scripps ’18). “On Fridays, I have six students working in the shop,” Schultz Reed explains. “It’s very social. Everybody’s chatting, everybody’s doing something, music is on. And—” here she grins wickedly—“I bring brownies on Fridays.”

ITEM: Class cane

ITEM: Class cane