To enter Los Angeles County from the southeast, follow Pacific Coast Highway through Seal Beach and onto a bridge spanning Los Cerritos Wetlands and the San Gabriel River. Off to your left, the marshy expanse turns to ocean. On your right, factory smokestacks stand against a hazy mountain range. The four-lane road narrows as it rises over the swamp. Go about a quarter mile until you reach a stoplight, where the road levels and widens again. You’re in Long Beach now. There’s a Whole Foods on the left if you’d like a snack.

To enter Los Angeles County from the southeast, follow Pacific Coast Highway through Seal Beach and onto a bridge spanning Los Cerritos Wetlands and the San Gabriel River. Off to your left, the marshy expanse turns to ocean. On your right, factory smokestacks stand against a hazy mountain range. The four-lane road narrows as it rises over the swamp. Go about a quarter mile until you reach a stoplight, where the road levels and widens again. You’re in Long Beach now. There’s a Whole Foods on the left if you’d like a snack.

Crossing this kind of imaginary line on a ho-hum stretch of highway is hardly noteworthy for drivers. Likewise for cyclists, able to coast up the easy incline in their own lane. But since I’m on foot, my experience is more visceral. I toe the rightmost white line of the bike lane and feel the surprising definition of the paint underfoot. I hurdle a semicircle of fibrous black rubber, being careful not to land in a puddle of shattered window glass. Still, I’m thankful to be on the road, rather than slogging through the mud as I did several days before. As for that imaginary line, it still isn’t real, just like that tall can of coconut water isn’t really a glass of champagne. Sure tastes like sweet, small victory though. Cheers to staying alive and feeling it, too.

At a table outside the Whole Foods, four cyclists who blew right past me on the bridge sit eating fruit and potato chips.

“How long have you been running, man?”

“Since Mexico. Only 30 more miles till L.A.”

“Damn, dude! That’s wild. I’ve never even thought of going that far.”

“Ha, to be honest, I hadn’t either. Just went for it.”

The trip had come together quickly, almost foolishly so. I remember waiting to board an afternoon flight to San Diego while I took stock of my personal effects: a small CamelBak, an outdated guidebook, a four-year-old iPhone with a faulty battery, a sore left knee. Less than two weeks prior, I’d volunteered to travel the 150 miles from the Mexican border to downtown Los Angeles on foot, by myself, blazing the trail for others to make the journey this August. It would be called El Camino del Inmigrante—the Way of the Immigrant—a display of solidarity and a rallying cry for policy reform, an initiative proposed by my father.

A few months before, my father and I had completed the Camino de Santiago together, walking 500 miles from the Pyrenees to the Atlantic across northern Spain. And as it so often does, emerging from such a crucible subconsciously compelled us to apply the principles of pilgrimage to our own lives, framing our goals and pursuits as a journey necessary for self-actualization. For me, the rite marked a return to running and a renewed will to explore. For my dad, it provided a means of mobilizing other activists and allies, using an inherently spiritual framework as a forum for discussing worldly issues. CEO of the Christian Community Development Association and longtime crusader for immigration reform, he’s lived the past 25 years of his life in La Villita, a Mexican community on Chicago’s West Side, feeling the struggle of the undocumented American on a personal level while giving voice to it on a national one. He is just the man for this mission. As for me—restless, a little reckless and perpetually in search of purpose—I make the perfect scout. Vamos.

The real thing will be a 10-day affair, with dozens of walkers, plus nightly events and fellowship. (They will also be skipping the dangerous parts, for the record.) For this scouting trip, I’m giving myself only five days, on account of professional obligations back home.

Now, standing in International Friendship Park—as far southwest as you can go on U.S. soil—I slap the wrought-iron border fence as if to start a stopwatch and take off, hoping the dirt trails will prove a safer alternative to the sidewalk-less streets. Before long I’m high-stepping through the muddy chaparral down dead-end paths, dodging boulder-sized tumbleweeds. There are helicopters patrolling overhead, trying (I imagine) to catch me runnin’ dirty. But it isn’t just the danger or the adrenaline that gets my mind running wild. Rather, it begins with the diagnostic scan any runner naturally takes of his or her own body over those first few moments or first few miles, identifying any sensations—good, bad or otherwise—and weighing them against the reality of the distance ahead. For me, it’s a hyper-awareness that can’t help but radiate outward, connecting me to the street or the buildings or passersby.

Perhaps this is why so many people claim to do their best thinking on the move. Besides simply getting the blood flowing, the movement plants a tiny seed of symbiosis, sprouting into curiosity, empathy and compassion.

I make it out of the dirt-road labyrinth and up the Silver Strand to Coronado. Into San Diego via ferry and on to La Jolla, where I sleep in a van with a minimalist friend from college. Past Torrey Pines Golf Course, merging onto the sidewalks of Highway 101, I shuffle through Del Mar, then Encinitas, then Carlsbad, straight into an ice bath in the tub of an Oceanside motel. Two days, 60 miles down. Not fully awake yet, I find myself staring down the end of an automatic rifle. One does not simply jog into Camp Pendleton, it seems. The chunky-necked marine lowers the barrel and points it toward the bus I have to take to the other side of the base. I hop out in San Clemente and continue on to Laguna Beach, fear-sprinting the last few miles on the shoulder of the narrow highway. I watch the sunset on a rock and go out on the town for some beers, at least one for each of today’s brushes with death. The fourth day is heavenly by comparison, past Newport, Huntington and Seal Beach on a long, leisurely stroll. And then, the bridge.

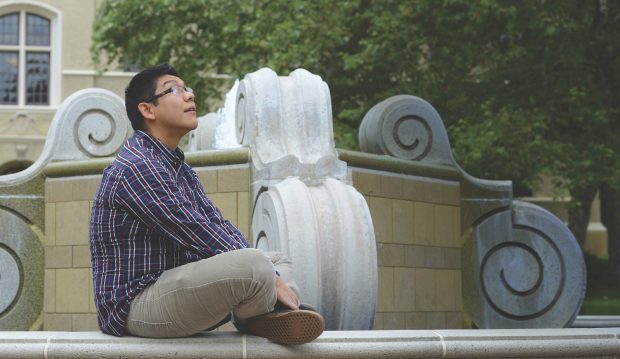

Back in L.A. County, mind as sharp as I can ever remember, I’m now headed in a clear direction. It’s exactly the opposite of how I left five years prior. Lining up alphabetically to take part in commencement exercises, I could see the banners strung upright from the lampposts along Stover Walk. They were beaded with water from the drizzling rain, the 2-D portraits of my outstanding friends and classmates taking on a slick, watery shine. They were the faces of Campaign Pomona: Daring Minds, celebrating an attribute supposedly shared by all of us receiving diplomas that day. It was an unsettling sight, because my own mind felt as blunt as a butter knife. I was in a fog, stuck in the mud, wondering how I would make myself useful—let alone successful—outside of Claremont.

To say that the opposite of rumination is motion—literally moving forward—seems strangely metaphorical. “Moving on” in a psychological or emotional sense somehow seems far more practical, even though this act of personal progress is itself a metaphor derived from corporeal movement. “Walk it off” is sound advice after being plunked by a fastball, but it’s hardly a tonic for indecision or identity crisis. Those are situations you reason and educate your way out of, carefully weighing the possible outcomes before starting down a path in earnest. It’s not called “Campaign Pomona: Daring Bodies,” mind you.

But as I returned home to Chicago as a new graduate, confused and neurotic, something strange began to happen. I started walking and running long distances, sometimes for exercise, sometimes because I was too broke for bus fare, but mostly because I didn’t know what else to do. And the more I moved from point to point—across the neighborhood, across the city, across finish lines—the more connected it all seemed to be. Not just this house to that house or this train station to that office building, but this community to that one, this reality to one a world apart. After an interdisciplinary education from a liberal arts college, this was my graduate course in Applied Everything. Each discrete skill was plotted on a map, and now I was learning to connect these disciplines to forge a purposeful path, one that had now led me back to where this meandering journey began.

I say goodbye to my new cyclist friends at the Whole Foods and jog the last few miles into Cambodia Town, Long Beach, where I stay for the night. Up and out of there at the crack of dawn, my fifth and final day seems almost ceremonial, just an easy 20-mile trot up the L.A. River bike path, through Skid Row and straight to the Westin Bonaventure downtown, the host hotel for the annual CCDA conference and the end point of the Camino. I slap the side of the building as if to turn off the stopwatch and call my dad. It’s done and dusted—a clear, walkable line from the wrought-iron fence to a shiny marble bench there at the valet stand. I take a seat and stare down at my shoes. They’re still caked with dried mud from the border field.

To claim that I suddenly understand the struggle of the immigrant because I ran a long way up a scenic trail would be ridiculous. I don’t; I never will. If anything, an affinity for recreational pain is proof that I’ve suffered—truly suffered—very little in my lifetime. But to reduce physical effort to mere sport may be just as misguided. I’ve seen aimless tours of a city open the mind to life’s beautiful web of alleyways and back roads. I’ve seen a cross-country trek take a father-son relationship from small talk to real talk. And I’ve felt a boldness of body spark an audacity of mind. So to say that this journey has made me a more engaged and empathetic individual, and that it may yet play a tiny role in some big change—well, that doesn’t sound ridiculous at all.

The following day I return home. There’s a letter from Pomona in my mailbox, announcing the conclusion of the historically successful Daring Minds campaign. And upon seeing it, instead of that undeserving, stuck-in-the-mud feeling from five years back, I feel proud, knowing that there was something daring in me all along. The only difference was, I had to dare feetfirst and work my way up.

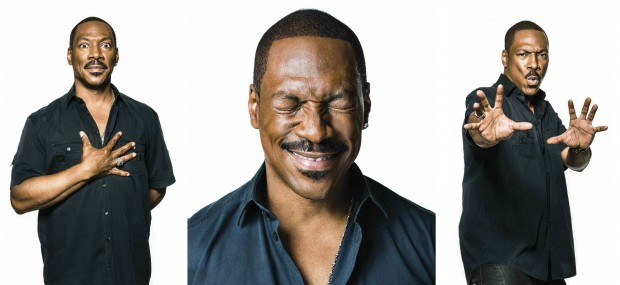

In his New York Times bestseller Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, Ashlee Vance ’00, veteran tech journalist and TV host of Bloomberg’s Hello World, reports on the daring business titan’s life and the rise of his innovative companies in finance, the auto industry, aerospace and energy. With exclusive, unprecedented access to Musk, his family and friends, Vance interviewed nearly 300 people for a book hailed as “masterful,” a “riveting portrait,” and “the definitive account of a man whom so far we’ve seen mostly through caricature.” Vance talked to PCM’s Sneha Abraham about the journey of the book and about Musk—a man both lauded and lambasted.

In his New York Times bestseller Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, Ashlee Vance ’00, veteran tech journalist and TV host of Bloomberg’s Hello World, reports on the daring business titan’s life and the rise of his innovative companies in finance, the auto industry, aerospace and energy. With exclusive, unprecedented access to Musk, his family and friends, Vance interviewed nearly 300 people for a book hailed as “masterful,” a “riveting portrait,” and “the definitive account of a man whom so far we’ve seen mostly through caricature.” Vance talked to PCM’s Sneha Abraham about the journey of the book and about Musk—a man both lauded and lambasted.

Jaureese Gaines ’16 and Maxine Solange Garcia ’16

Jaureese Gaines ’16 and Maxine Solange Garcia ’16 Stephen Glass ’57 and Sandra Dunkin Glass ’57

Stephen Glass ’57 and Sandra Dunkin Glass ’57  Neuroscience Professor Nicole Weekes and Vivian Carrillo ’16

Neuroscience Professor Nicole Weekes and Vivian Carrillo ’16 Viraj Singh ’19 and Jonathan Wilson ’19

Viraj Singh ’19 and Jonathan Wilson ’19 Ed Tessier ’91 and Professor Emeritus of Sociology Bob Herman ’51

Ed Tessier ’91 and Professor Emeritus of Sociology Bob Herman ’51 Cesar Meza ’16 and Draper Center Director Maria Tucker

Cesar Meza ’16 and Draper Center Director Maria Tucker Jamila Espinosa ’16 and Lucia Ruan ’16

Jamila Espinosa ’16 and Lucia Ruan ’16 Richard Bookwalter ’82 and Galen Leung ’82

Richard Bookwalter ’82 and Galen Leung ’82 Shadiah Sigala ’06 and Kaneisha Grayson ’06

Shadiah Sigala ’06 and Kaneisha Grayson ’06 Dan Stoebel ’00 and Biology Professor Daniel Martínez

Dan Stoebel ’00 and Biology Professor Daniel Martínez Michelle Chan ’17 and Sophia Sun ’18

Michelle Chan ’17 and Sophia Sun ’18

Spirits of Saturn was a fine, white powder that 17th-century women smoothed into their skin. Also known as Venetian ceruse, it hid smallpox scars, spots and blemishes, transforming faces into a fashionable pallor. It also slowly poisoned the wearer—it was made of powdered lead.

Spirits of Saturn was a fine, white powder that 17th-century women smoothed into their skin. Also known as Venetian ceruse, it hid smallpox scars, spots and blemishes, transforming faces into a fashionable pallor. It also slowly poisoned the wearer—it was made of powdered lead.

Most of the people gathered around the card tables at the Senior Center in Longmont, Colo., this morning seem to be my age or older—in their 60s or 70s. They sit three or four to a table and peek at their cards, as I do at mine.

Most of the people gathered around the card tables at the Senior Center in Longmont, Colo., this morning seem to be my age or older—in their 60s or 70s. They sit three or four to a table and peek at their cards, as I do at mine.

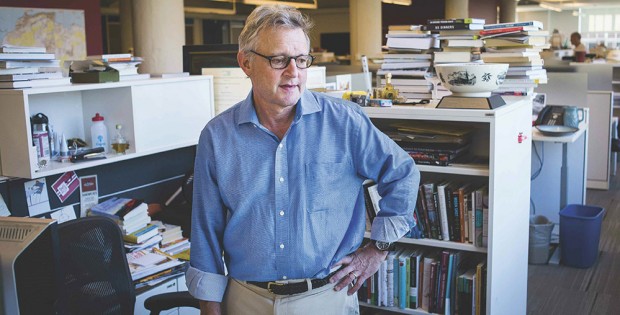

Joe Palca’s cubicle in NPR’s Washington, D.C., headquarters is strewn with bicycle gear from his daily commute, assorted piles of books about science, and random objects: a can of mackerel, a leaf-shaped bottle of maple syrup. From this cluttered perch, the longtime science correspondent has the power to shape what becomes news. If Joe Palca ’74 decides a story is worth putting on the air, roughly a million listeners hear it. And if he misses a story, well, some of those listeners may never hear about it.

Joe Palca’s cubicle in NPR’s Washington, D.C., headquarters is strewn with bicycle gear from his daily commute, assorted piles of books about science, and random objects: a can of mackerel, a leaf-shaped bottle of maple syrup. From this cluttered perch, the longtime science correspondent has the power to shape what becomes news. If Joe Palca ’74 decides a story is worth putting on the air, roughly a million listeners hear it. And if he misses a story, well, some of those listeners may never hear about it. Of course, not all subjects have such inherent drama. Still, Palca says, scientists are not the cold-blooded, calculating creatures they are often presumed to be. “I’m sick of the caricature, of the white lab coat. The lab coat says ‘I’m an expert, not a person.’”

Of course, not all subjects have such inherent drama. Still, Palca says, scientists are not the cold-blooded, calculating creatures they are often presumed to be. “I’m sick of the caricature, of the white lab coat. The lab coat says ‘I’m an expert, not a person.’”

“She gets it. She gets that it’s transformative, not only for the kids who come in, but for the neighborhood. This is a community that wants to be known for something more than where Rodney King was beaten. This is something that’s a spark.”

“She gets it. She gets that it’s transformative, not only for the kids who come in, but for the neighborhood. This is a community that wants to be known for something more than where Rodney King was beaten. This is something that’s a spark.”