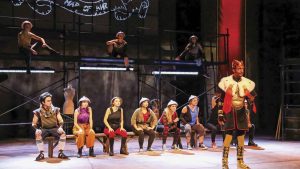

The Glee Club at Durham Cathedral in England, conducted by Donna M. Di Grazia, David J. Baldwin Professor of Music. Photo by John Attle

Going on tour has long been one of the high notes for the Glee Club. But the Gleeps, as they like to call themselves—think Glee People—had been grounded since 2020 before a giddy two-week tour to England and Scotland in May.

A planned trip to Europe in 2020 was canceled by the COVID-19 shutdown, and the next two years were limited to small outdoor performances in Claremont and a Southern California tour. When the Glee Club took flight again in May, even some alumni from the past few years joined in after missing their chance.

“For those of us in the Class of 2020, a trip to Spain was supposed to be the perfect ending to our already incredible experience in the ensemble,” says Matthew Cook ’20, a former Glee Club co-president and a second-generation Gleep: His mother, Melissa Cook ’90, also sang in the ensemble. “We didn’t even get the chance to sing a full concert in our last semester, let alone go on tour,” says Cook, who earned a master’s in vocal arts from USC in May. “To be able to sing with the 2023 Glee Club and go on an international tour that I lost out on as a student, I feel like I got some closure in that part of my life that was disrupted by the pandemic.”

After arriving in London, the Glee Club opened with a concert in St. James’s Church, Piccadilly, one of four benefit concerts for local charities. The choir also sang for a Eucharist service in Cambridge’s Trinity College Chapel, traveled to York for a concert in St. Michael le Belfrey and held another in Durham Cathedral (in Durham, of course). In Scotland, they performed in St. Andrews in a joint concert with the St. Andrews University Madrigal Group and closed their tour in Edinburgh with a concert at St. Giles’ Cathedral.

In more normal times, the Glee Club travels each year, with about one international trip for every three domestic tours to give each class an opportunity to go overseas. Other trips abroad have included Italy (2016), Poland (2012)and Germany (2006).

Besides alumni performers, there was an extra alumni assist on this one: Catherine John ’05, a violinist who works as a concert tour manager, helped plan the trip with Donna M. Di Grazia, the David J. Baldwin Professor of Music and conductor of the Glee Club and College Choir, and Elizabeth Champion, the Music Department’s concert production manager and tour manager. “The Glee Club sent me a very kind thank-you note, which I will cherish always,” John says.

Inspired by Myrlie Evers-Williams ’68 and the gift of her archives to the College, Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg have donated their collection of more than 1,600 press photographs documenting the civil rights movement to the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College in her honor. The Mattis-Hochberg photos include scenes of resistance, acts of civil disobedience and images of civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, James H. Meredith as well as photos of Evers-Williams.

Inspired by Myrlie Evers-Williams ’68 and the gift of her archives to the College, Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg have donated their collection of more than 1,600 press photographs documenting the civil rights movement to the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College in her honor. The Mattis-Hochberg photos include scenes of resistance, acts of civil disobedience and images of civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, James H. Meredith as well as photos of Evers-Williams.

Rhino Records, a Claremont Village staple since 1974, has closed its doors. That elicited a Twitter lament from Professor of Politics David Menefee-Libey (@DMenefeeLibey) and responses from Aditya Sood ’97 and Brian Arbour ’95.

Rhino Records, a Claremont Village staple since 1974, has closed its doors. That elicited a Twitter lament from Professor of Politics David Menefee-Libey (@DMenefeeLibey) and responses from Aditya Sood ’97 and Brian Arbour ’95.