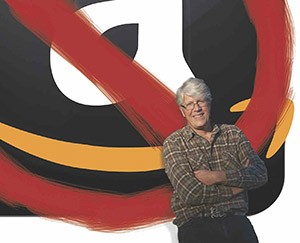

THE WORDS THAT galvanized a thousand authors to speak out against a powerful corporate retailer were written along a dirt road, in an 8-by-10 shack, by a wispy-haired, self-described “wimp.”

THE WORDS THAT galvanized a thousand authors to speak out against a powerful corporate retailer were written along a dirt road, in an 8-by-10 shack, by a wispy-haired, self-described “wimp.”

This past year Amazon spent many months in testy negotiations with Hachette, the fourth-largest book publisher in the U.S. When no agreement had been reached by May, Amazon began delaying shipment of Hachette books, shutting down pre-orders, and even removing the publisher’s titles from its all-important recommendation algorithms.

Such gestures aren’t trivial—when the entity responsible for selling 40 percent of America’s printed books makes yours difficult to buy, sales drop.

Sitting here on the deck of his spacious summer house overlooking Maine’s pristine Muscongus Bay, thriller writer Douglas Preston ’78 clearly isn’t worried for his own livelihood. He’s published more than a dozen best-sellers and cultivated a devout following that will find him with or without Amazon.

But what keeps him up at night—and what spurred him to write 500 words that put his name in the headlines and a sizable thorn in Amazon’s side—is thinking about all the young authors that he says have been “held hostage in the middle of a back-room deal between two big corporations.”

In June, Preston penned an informal letter about Amazon’s actions, with the idea that a few writers might co-sign. After famous friends like Stephen King and Nora Roberts started spreading the word, the letter went viral, and within a matter of days more than 900 of his peers had gotten on-board and joined the group that Preston had dubbed “Authors United.”

It wasn’t a completely united front—a vocal contingent of self-published authors posted lengthy screeds online calling him a “one-percenter,” a “pinhead” and worse, while Amazon reps dismissed him in the press as “entitled” and “an opportunist.” When Amazon found out that he planned to publish his letter as a full-page ad in The New York Times, the company’s head of e-books tracked down his phone number and called to issue veiled threats and try to stop him.

Preston shrugs when he reflects on how the situation escalated and how he, improbably, became the face behind a movement that he never set out to lead.

“I’ve never been much of an activist about these things,” he says. “But [Amazon’s tactics] felt like an act of betrayal. We writers helped a struggling start-up become one of the world’s largest companies, and this is how they repay us?”

Amazon’s path to global dominance hasn’t come without making some enemies. CEO Jeff Bezos has internally referred to his team’s business strategy as “the Gazelle Project,” in that Amazon approaches publishers “the way a cheetah would pursue a sickly gazelle.”

The Hachette dispute is far from Amazon’s first: in 2010 it deleted the “buy” option for all MacMillan books, which quickly forced the publisher to cave in during negotiations. The company often paints publishing houses as middlemen and gatekeepers—relics from another era whose skills at distribution and publicity have been rendered moot by instant downloads and viral word-of-mouth.

Many self-published authors agree. Sci-fi writer Hugh Howey has collected more than 8,000 signatures for a Change.org petition arguing that companies like Hachette are “resisting technology” rather than adapting to the changing times.

Preston, naturally, begs to differ. He sees publishers as vital curators, editors and investors, and believes that the biggest challenge for Authors United is, ironically enough, telling the right stories.

Here’s his: it’s 1978, and he’s a fresh-faced college grad creating communications content for the American Museum of Natural History. The job pays peanuts but lets him explore all of the museum’s hidden treasures, from majestic butterfly exhibits to a hair-raising “dinosaur graveyard” in the basement.

A few years into the gig, he gives a tour to an editor named Lincoln Child, who suggests that he pull his anecdotes into a book.

While novels can often be cobbled together on nights and weekends, Preston’s journalistic writing would require some heavy daytime reporting. As a first-time author, Preston isn’t in a position to drop everything to write, but his publisher St. Martin’s Press gives him an advance of $7,200 that lets him take six months off from his job.

“Without that cash, there’d be no first book and I might not even be doing this for a living right now,” he says.

The experience made Preston recognize the importance of publishers as venture capitalists for ideas—a tradition that, in a sense, extends back to the Renaissance, when royal families like the Medicis funded artwork by Michelangelo and Sandro Botticelli.

“These publishers supported me when I was unknown and believed in me enough to keep releasing my books even when the first few didn’t sell,” says Preston, who’s been with Hachette for 20 years. “What’s lost in the narrative is that, if authors couldn’t get advances, an awful lot of extremely important books wouldn’t get written.”

As with most business disputes, Amazon and Hachette’s boils down to dollar signs. Their main disagreement has revolved around e-books, which now make up almost a third of the market. Currently 30 percent of each e-book’s revenues go to Amazon, and 70 percent go to Hachette, which then carves out a cut for the author (usually 10 to 15 percent). While nobody knows exactly what was happening behind closed doors during negotiations, Amazon was reportedly pressing for 50 percent of revenues.

What’s also at stake are e-book prices themselves. Amazon has famously been selling many e-books at a loss, and says that prices above $9.99 hurt overall sales. Hachette, meanwhile, has been reluctant to set a precedent for lower prices that might cannibalize hardcover sales.

Preston says he has no particular problems with $10 e-books, but at the same time is flummoxed by the animosity leveled at authors whose books are being sold for a few dollars more.

“Some people have said e-books should be cheaper because they’re ‘just words,’ but then why isn’t anybody out picketing the makers of ‘Grand Theft Auto’ for charging $65 for a video game that’s ‘just electrons?’” he asks. “It devalues all the work that goes into the creative process. Is every book really worth just $9.99 to you?”

Amazon has likened e-books to paperbacks, another technological advance that lowered literature’s costs but also allowed for its increased availability. Many authors would counter that the Amazon-driven trend toward lower and lower e-book prices threatens the long-term viability of the entire profession.

“Amazon is doing the same thing Spotify is doing—treating creative content as though it were a commodity, like a TV set or a vacuum,” Preston says. “They’ve spurred a massive price devaluation of books that’s caused consumers to expect artificially low prices—and the net result is that it’s now exceedingly difficult for young authors to make a living.”

It’s not just first-time authors who’ve felt the pinch, which is why many authors were wary about signing a letter like Preston’s that would pit them against such a massive retail juggernaut. Novelist Lucy Ferriss ’75 was gung-ho about Authors United last summer, but as the publication date of her next book approached, she started reflecting on the wide reach of Amazon, which owns both the review site Goodreads and Audible (the seller of the majority of the world’s audiobooks).

“It becomes much more real when your own sales are tied into it,” Ferriss says. “It’s startling to realize how much of my personal investment as an author is caught up in getting good results with Amazon.”

Despite her reservations, she’s stayed on-board—in no small part because of Preston’s dedication. She recalls that when he and his brother Richard ’76 (a fellow writer) joined Pomona’s literary magazine Passwords, it only took a matter of weeks for her team of editors to voluntarily hand over control.

“They were impeccably organized, they had goals, and we were hopelessly incompetent,” she says with a laugh. “With Authors United, it doesn’t surprise me that Doug’s been able to essentially herd an army of feral cats. Once he decides to get something done, he does it.”

Since the initial letter, Authors United tried to reach out directly to members of the Amazon Board, with no luck. Preston was also approached by a team of prestigious pro bono lawyers who will be submitting a formal brief for the Department of Justice that outlines Amazon’s antitrust violations. He hopes it will encourage, if not an actual lawsuit, then at least more transparency on the part of retailers and publishers’ business dealings.

“Amazon makes most publishers sign non-disclosure agreements, such that we don’t even know what’s going on with these contracts,” he says. “What’s the nature of these relationships, and what is Amazon asking for? The DOJ has to bring this all out in the open so the American people can look at the facts for themselves.”

When I met with Preston on a crisp autumn morning in October, he sounded frustrated and a tad overwhelmed. He was promoting the publication of his third novel of 2014, gearing up for a book fair in United Arab Emirates, working on the next installment in his popular “Pendergast” series, and fielding phone calls from journalists about the ongoing publishing feud.

“Truth be told, I’m sick and tired of the situation, and would love to get rid of Authors United and go back to writing books,” he told me then.

Less than a month later, Hachette and Amazon reached a deal that made Hachette responsible for setting e-book prices, but also gave Amazon the opportunity to offer “specific financial incentives for Hachette to deliver lower prices.”

Preston views the resolution as just the end of one battle in a larger war for writers, publishers and retailers. Despite the tedious and thankless nature of his role, he says he takes comfort in the fact that his efforts have put a spotlight on the changing landscape of his industry—and the tricky economics that come with being an author in the digital age.

“If nothing else, it’s reassuring to look at the list of folks who’ve signed the letter and see everyone from cookbook authors and sci-fi writers to poets and Nobel laureates,” he says. “I’ve been in this industry long enough to know that it’s rare to get writers to agree on anything.”

The Templars, the Witch, and the Wild Irish

The Templars, the Witch, and the Wild Irish Downstream

Downstream Exploring the Salish Sea

Exploring the Salish Sea More Studies in Ethnomethodology

More Studies in Ethnomethodology

Tokens on the Table (A Tip is Not Enough) and Contrary Mary (All in Good Time)

Tokens on the Table (A Tip is Not Enough) and Contrary Mary (All in Good Time) Soundtracks of Asian America

Soundtracks of Asian America

THE WORDS THAT galvanized a thousand authors to speak out against a powerful corporate retailer were written along a dirt road, in an 8-by-10 shack, by a wispy-haired, self-described “wimp.”

THE WORDS THAT galvanized a thousand authors to speak out against a powerful corporate retailer were written along a dirt road, in an 8-by-10 shack, by a wispy-haired, self-described “wimp.”

ney, Aaron Becker ’96 offers the second installment in an intended trilogy of brightly colored fantasy adventures without words.

ney, Aaron Becker ’96 offers the second installment in an intended trilogy of brightly colored fantasy adventures without words. Joan Benson ’46, a champion of the clavichord in the modern world, offers a method book for practitioners and enthusiasts alike, including a master class DVD and a CD of Benson performing.

Joan Benson ’46, a champion of the clavichord in the modern world, offers a method book for practitioners and enthusiasts alike, including a master class DVD and a CD of Benson performing. Reanne Hemingway-Douglass ’63 tells the little-known World War II story of an escape route that the French Resistance used to rescue Allied airmen shot down over France.

Reanne Hemingway-Douglass ’63 tells the little-known World War II story of an escape route that the French Resistance used to rescue Allied airmen shot down over France.

clash between an old family legacy, tribal land rights, and a marriage in trouble results in a suspicious death, threatening the lives of those who try to solve it.

clash between an old family legacy, tribal land rights, and a marriage in trouble results in a suspicious death, threatening the lives of those who try to solve it.

A National Book Award finalist, Professor of English Claudia Rankine’s meditation on race recounts the racial aggressions of daily life in America in a progression of revealing vignettes.

A National Book Award finalist, Professor of English Claudia Rankine’s meditation on race recounts the racial aggressions of daily life in America in a progression of revealing vignettes. The latest from Chandra, author of the bestseller Sacred Games, is

The latest from Chandra, author of the bestseller Sacred Games, is  Ved Mehta ’56, the author of 27 books and many articles, has released

Ved Mehta ’56, the author of 27 books and many articles, has released

Though it is set in Queens, Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s latest novel,

Though it is set in Queens, Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s latest novel,

So did Hollywood seek out presidents or did presidents seek out Hollywood? Peretti says the answer is yes and yes. The attraction was mutual. “Presidents were fascinated by the cultural power wielded by the movies, while moviemakers were drawn to the dramatic realm of power in the real world,” says Peretti.

So did Hollywood seek out presidents or did presidents seek out Hollywood? Peretti says the answer is yes and yes. The attraction was mutual. “Presidents were fascinated by the cultural power wielded by the movies, while moviemakers were drawn to the dramatic realm of power in the real world,” says Peretti. During his Pomona College days, Dan Hickstein ’06 landed a prestigious

During his Pomona College days, Dan Hickstein ’06 landed a prestigious  The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images.

The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images. “I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.”

“I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.” If you’re reading James Thurber and Robert Benchley and composing comedic poetry at the tender age of 7, then writing a book that examines humor from every conceivable angle doesn’t feel like that much of a stretch. Indeed, when David Misch ’72 began putting together Funny: The Book three years ago, it felt like the next logical step in a four-decade career that has included stints as a comedic folk singer, stand-up comedian and writer for such shows as Mork and Mindy and Saturday Night Live.

If you’re reading James Thurber and Robert Benchley and composing comedic poetry at the tender age of 7, then writing a book that examines humor from every conceivable angle doesn’t feel like that much of a stretch. Indeed, when David Misch ’72 began putting together Funny: The Book three years ago, it felt like the next logical step in a four-decade career that has included stints as a comedic folk singer, stand-up comedian and writer for such shows as Mork and Mindy and Saturday Night Live.