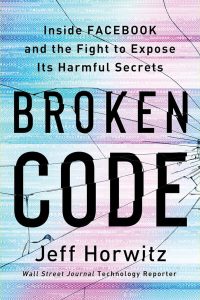

To understand exactly what has happened at Meta with its lineup of products such as Facebook and Instagram, ask Jeff Horwitz ’03. The investigative journalist for The Wall Street Journal has been on the Meta beat for more than four years with the goal of revealing the inner workings—and management failures—within Facebook’s Silicon Valley walls.

Horwitz tracked how often Facebook chose growth over quality by ignoring misinformation on the site and by lack of moderation, resulting in the investigative series The Facebook Files for the WSJ in 2021. He added additional reporting for his newly released book, Broken Code: Inside Facebook and the Fight to Expose Its Harmful Secrets. In it, Horwitz also looks at how Instagram managers ignored warning signs that the platform seriously damaged body image perceptions for teen girls around the world.

Journalist David Silverberg spoke to Horwitz for Pomona College Magazine to learn more about his yearslong process in investigating Meta, his view on Mark Zuckerberg’s role in the company’s missteps, and why he warns parents to be extremely careful about how their children use social media.

PCM: Technology reporters have been writing that those who run Facebook haven’t learned from the mistakes they made in 2016 and beyond. What’s your take on that?

Horwitz: One of the really fascinating things that came out of the book is that there was a period of time where Facebook invested really heavily in safety and in understanding its product. Then those people made recommendations on how to change the product in ways that would certainly mitigate a lot of the harms from its product, such as misinformation, the formation of massive groups like QAnon, conspiracy movements. There were approaches to fixing this that these folks developed but the problem was they came at the cost of engagement and usage of a platform. Meta and in particular Mark Zuckerberg were not willing to accept that. So the company has actually laid off a lot of the people who are doing this, partly because they aren’t interested in pursuing the work, and partly because they view these people as a fifth column inside the company that is more loyal to their sense of public good than to their sense of what is good for Meta.

The problems of 2016 and 2020 have by and large not been addressed. The ease with which any motivated entity can trick the algorithm into spewing out spam or political content hasn’t fundamentally changed.

PCM: Your book found that Zuckerberg’s role in how his company chose growth over content moderation was a stark contrast to how some other CEOs and founders run their companies. How so?

Horwitz: Everything flows from Mark, and that’s why he’s kind of an anomaly in the tech space at this point. The other big founders tend to step back or work on side hobbies such as Twitter—look at Elon Musk—and with Google and Microsoft, those founders have moved along in their lives and Mark hasn’t. And I think one of the things that’s really striking is he is often describing the open internet where anyone can write what they want but he neglects to discuss what Facebook became, which is an extremely powerful content recommendation engine that will recommend literally anything that will keep people on the platform more often.

No one understood that introducing a reshare button was going to actually produce higher levels of misinformation on the platform because the more times a thing gets shared, it turns out based on the company’s internal research, the less likely it’s going to be true and more likely it’s going to be sensationalist.

PCM: What I also found compelling about the book, and The Facebook Files, was how you established a relationship with Frances Haugen, the famous whistleblower and ex-manager from Facebook who ended up testifying to the U.S. Senate about how the company knew about the potential harm they were causing to both adults and children. What did you think about what she did for you and the investigation?

Horwitz: Frances is an extremely unusual human being in the sense that most whistleblowers burn out first and then they quit in a huff or they get laid off and then they decide they want to talk. I think it’s very unusual for someone to begin at square one and that she couldn’t live with herself if she didn’t do her best to bring [Facebook’s issues] to the world’s attention.

This is somebody who was breaching the confidence of their employer for a very valid purpose and I think she had a lot on the line.

PCM: Before you delved into writing about Meta, you also wrote about other businesses for The Associated Press when you worked there between 2014 and 2019. How did your stint at AP help you with your career?

Horwitz: I was hired for their Washington investigative team and Donald Trump’s candidacy sort of ate my career there. I think because I had a business focus, I was originally put onto it in 2015 as, oh, hey, here’s another flash-in-the-pan candidate. We’ve seen many of them like that. Every cycle has some sort of Herman Cain-type figure who appears briefly on the horizon and then disappears. And I think that was originally the assumption about Donald Trump’s candidacy as well. Obviously that never happened.

So it was a really interesting time in terms of the work. But at the same time—I get into this a little bit in the book—it was kind of a depressing time because it really became apparent in 2016 that the only way news could get traction was if it appealed to partisans on either side and, in particular, if it appealed to partisans on Twitter.

I think one of the ways I ended up covering Facebook for The Wall Street Journal is I wanted to figure out that if the news and information ecosystem is permanently broken, then what’s going to replace it? And maybe I should be writing about that. So that’s how I ended up covering Meta.

PCM: How would you characterize the time you spent at Pomona?

Horwitz: One of the best things that happened at Pomona College for me was I got David Foster Wallace when he was teaching creative writing.

I also got into journalism via the student newspaper, and my first ever story for them was covering Professional Bull Riders Association events in Anaheim. It’s not like bull riding is a thing that I am deeply passionate about, but to have my press seat next to ESPN’s was pretty fun.

I began to feel more like an investigative reporter when I wrote on issues at the school, such as when I broke a story about grade inflation at Pomona while I was there. In 2000, The Student Life also reported on a very nasty fight over dining hall unionization and what we saw as some of the labor-busting tactics that the school undertook. I’m grateful to Pomona for a lot of things, but one of them is it kind of turned me on to questioning institutions.

Editor’s note: Pomona’s dining hall workers have been unionized since 2013, and the most recent collective-bargaining agreement provides a minimum wage of $25 an hour for all dining and catering workers by July 1, 2024.

PCM: Lastly, what’s your social media usage like these days? I assume you’re more careful than most considering everything you know about Facebook and Instagram.

Horwitz: I like cat videos as much as the next guy, but I’ve never been a super-heavy user.

So while I don’t have kids, I will say that I have been pretty damn strenuous in telling friends that it’s a good idea to be, shall we say, conservative with how much social media children use for a whole bunch of reasons. [Editor’s note: Since the interview, Horwitz has reported on Meta’s struggle to prevent pedophiles from using Facebook and Instagram in violation of its policies against child exploitation.] An interesting part of the book was revealing how the company really did define what was good for users and whatever made them use the product more. In other words, they must like it if they’re using it more, right? Not so fast.

In The Presidents and the People, Corey Brettschneider ’95 explores how five American presidents in different eras abused their power and how citizens fought back to restore democracy.

In The Presidents and the People, Corey Brettschneider ’95 explores how five American presidents in different eras abused their power and how citizens fought back to restore democracy. Chanté Griffin ’00 helps readers develop a vision of anti-racism and move toward racial healing in Loving Your Black Neighbor as Yourself: A Guide to Closing the Space Between Us.

Chanté Griffin ’00 helps readers develop a vision of anti-racism and move toward racial healing in Loving Your Black Neighbor as Yourself: A Guide to Closing the Space Between Us. As an editor of American Aesthetics: Theory and Practice, Walter B. Gulick ’60 proposes a distinctly American approach to aesthetic judgment and practice through this collection of essays.

As an editor of American Aesthetics: Theory and Practice, Walter B. Gulick ’60 proposes a distinctly American approach to aesthetic judgment and practice through this collection of essays. In his debut novel The Emperor and the Endless Palace, Justinian Huang ’09 crafts a genre-bending queer Asian love story that unfolds across multiple timelines.

In his debut novel The Emperor and the Endless Palace, Justinian Huang ’09 crafts a genre-bending queer Asian love story that unfolds across multiple timelines. Jade Sasser ’97 explores climate-driven reproductive anxiety, placing race and social justice at the center, in Climate Anxiety and the Kid Question: Deciding Whether to Have Children in an Uncertain Future

Jade Sasser ’97 explores climate-driven reproductive anxiety, placing race and social justice at the center, in Climate Anxiety and the Kid Question: Deciding Whether to Have Children in an Uncertain Future The Five Ranks of Zen: Tozan’s Path of Being, Nonbeing and Compassion is a comprehensive guide to the teachings of Zen Buddhism by American Zen teacher Gerry Shishin Wick ’62.

The Five Ranks of Zen: Tozan’s Path of Being, Nonbeing and Compassion is a comprehensive guide to the teachings of Zen Buddhism by American Zen teacher Gerry Shishin Wick ’62. As president emerita of Kalamazoo College and trustee emerita of Pomona College, Eileen B. Wilson-Oyelaran ’69 presents a fresh perspective on higher education leadership in The New College President: How a Generation of Diverse Leaders Is Changing Higher Education.

As president emerita of Kalamazoo College and trustee emerita of Pomona College, Eileen B. Wilson-Oyelaran ’69 presents a fresh perspective on higher education leadership in The New College President: How a Generation of Diverse Leaders Is Changing Higher Education.

One Day This Tree Will Fall

One Day This Tree Will Fall Quiet Voice, Awesome Power

Quiet Voice, Awesome Power How Much Are These Free Books? True Tales from the Book Nook

How Much Are These Free Books? True Tales from the Book Nook Learning and Teaching Creativity

Learning and Teaching Creativity The Saplings Think of Us as Young

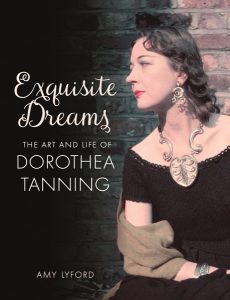

The Saplings Think of Us as Young Exquisite Dreams: The Art and Life of Dorothea Tanning

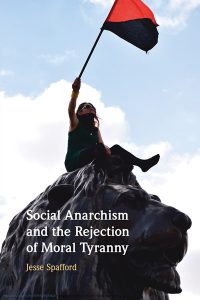

Exquisite Dreams: The Art and Life of Dorothea Tanning Social Anarchism and the Rejection of Moral Tyranny

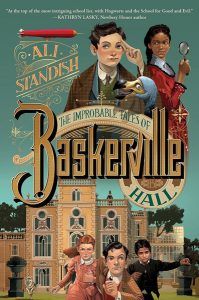

Social Anarchism and the Rejection of Moral Tyranny The Improbable Tales of Baskerville Hall

The Improbable Tales of Baskerville Hall

A Stone Is a Story

A Stone Is a Story Don’t Look Away: Art, Nonviolence, and Preventive Publics in Contemporary Europe

Don’t Look Away: Art, Nonviolence, and Preventive Publics in Contemporary Europe Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother

Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother American Burial Ground: A New History of the Overland Trail

American Burial Ground: A New History of the Overland Trail The Seeing Garden

The Seeing Garden Capacity beyond Coercion: Regulatory Pragmatism and Compliance along the India-Nepal Border

Capacity beyond Coercion: Regulatory Pragmatism and Compliance along the India-Nepal Border Becoming a Social Science Researcher: Quest and Context

Becoming a Social Science Researcher: Quest and Context Warnings: The Holocaust, Ukraine, and Endangered American Democracy

Warnings: The Holocaust, Ukraine, and Endangered American Democracy Just in Time: Temporality, Aesthetic Experience, and Cognitive Neuroscience

Just in Time: Temporality, Aesthetic Experience, and Cognitive Neuroscience Ashlee Vance ’00, author of the bestseller Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, turns his attention to the business of space in his latest book, When the Heavens Went on Sale: The Misfits and Geniuses Racing to Put Space Within Reach. Vance follows four startup companies—Astra, Firefly, Planet Labs and Rocket Lab—as they race to launch rockets and satellites into orbit. PCM’s Lorraine Wu Harry ’97 spoke to Vance about the book, the corresponding HBO show he is producing and, of course, Elon Musk. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ashlee Vance ’00, author of the bestseller Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, turns his attention to the business of space in his latest book, When the Heavens Went on Sale: The Misfits and Geniuses Racing to Put Space Within Reach. Vance follows four startup companies—Astra, Firefly, Planet Labs and Rocket Lab—as they race to launch rockets and satellites into orbit. PCM’s Lorraine Wu Harry ’97 spoke to Vance about the book, the corresponding HBO show he is producing and, of course, Elon Musk. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.