The master of light and space delivered the remark with a smile. “I have a business of selling blue sky and colored air,” James Turrell ’65 told a group of arts reporters after they had previewed his long-awaited retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. But if he counts exhibitions as sales, business is extraordinarily good this year. While Dividing the Light, Turrell’s Skyspace at Pomona College, continues to attract students, alumni and visitors to Draper Courtyard, celebrations of his work are popping up from coast to coast.

The centerpiece of the “Turrell festival,” as LACMA director Michael Govan calls it, is a trio of major museum exhibitions in Los Angeles, Houston and New York. LACMA’s James Turrell: A Retrospective is a five-decade survey, composed of 56 works, including sculptures, prints, drawings, watercolors, photographs and installations. “This is the largest exhibition of works by this artist assembled anywhere at any time,” Govan says. And it will have an unusually long, 10-month run (ending April 6, 2014), so that the expected thousands of visitors can experience the artist’s mind-bending installations as he wishes—slowly, silently, and singly or in small groups. As the museum director reminds guests, “The slower you go, the more you get.”

Rendering by Andreas Tjeldflaat. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Turrell traces his interest in light to an art history class at Pomona, where he began to see the beam of light emitted by a slide projector as something to look at, not just a means of illuminating something else. As his work evolved, light became his primary material and a path to perceptual discovery. The retrospective follows his career from early light projections in darkened rooms to holograms and “immersive environments” that surround viewers with other-worldly orchestrations of colored light and deceptive space.One large section of the show is devoted to Turrell’s Roden Crater project, which began to take shape in 1977 when the Dia Art Foundation provided funds for the artist to buy a dormant volcano near Arizona’s Painted Desert. With a goal of transforming the crater into an observatory of celestial events and perceptual phenomena, he intended to complete the job around 1990. Challenges of fundraising, engineering and construction have repeatedly extended the project. Now Turrell jokes, “I have said I would finish in the year 2000 and I will stick with that.” He likens himself to a graduate student who can’t seem to complete a doctoral thesis. But his biggest obstacle is the need for an unspecified amount of money, which he concedes is in “the millions.”

Despite persistent delays with Turrell’s magnum opus, the museum exhibitions attest to his productivity in other areas. Over the years, he has made a wide variety of drawings, prints and sculptural pieces related to the crater, as well as installations including floating volumes of projected light, environments that heighten perceptual awareness, and spatially disorienting Ganzfelds. None of his architectural Skyspaces are at the museums because of the difficulty of cutting holes in their walls and ceilings, but he has completed 82 of these structures, each tailored to a specific site. He has also developed Perceptual Cells, designed for one or two people to recline while watching a constantly changing program of phased and strobed light. In the cell at LACMA, called Light Reignfall, a single viewer lies on a narrow bed that slides into a closed chamber.

In Houston, the Museum of Fine Arts has devoted a huge portion of its gallery space to James Turrell: The Light Inside (through Septembber 22). Named for the subterranean installation that connects the museum’s two buildings under a street, the show is entirely drawn from the MFAH’s extensive collection. The museum acquired its first Turrells in the mid-1990s and went on to amass a holding that spans the artist’s career. While some works in the exhibition are familiar to the museum’s core audience, Tycho, a 1967 double-projection, is making its public debut. So is Aurora B, a 2010-11 piece from Turrell’s Tall Glass series, in which LED light is programmed to produce subtle shifts of color on rectangular panels of etched glass over long periods of time.

In New York, the Solomon R. Guggenheim has turned its spectacular rotunda into a Turrell. Called Aten Reign (and scheduled to remain in place until September 25), the installation is billed as “one of the most dramatic transformations of the museum ever conceived.” Turrell has converted the soaring central space of the Frank Lloyd Wright building into an enormous cylindrical volume of fluctuating light, both natural and artificial. Instead of opening to the sky, Skyspace-style, Aten Reign surrounds visitors with concentric lines of glowing color, which lead to the glass-covered oculus at the apex of the historic structure. Adjacent galleries offer more conventional works by Turrell as a complement to the dramatic installation.

The three exhibitions evolved from tentative plans for a traveling retrospective, says Govan, a long-time Turrell associate and former director of the Dia Art Foundation. Leaders of the Los Angeles and Houston museums began a conversation that expanded to include the Guggenheim. “But then we realized that James Turrell exhibitions don’t travel in the typical way because you end up building most of the works on site,” Govan says. The solution was “to do three shows all at once, but with different content.”

Serious Turrellians must see all three, of course. But that isn’t all. Kayne Griffin Corcoran Gallery has opened a new space at 1201 S. La Brea Ave. in Los Angeles, with Turrell’s assistance. The inaugural show of his work has closed, but he has a continuing presence in the gallery’s lighting and a Skyspace, furnished with comfortable chairs. And in Las Vegas, he has designed an installation for The Shops at Crystals, a high-end fashion center that’s encased in an explosive arrangement of angular walls. Turrell’s outdoor spectacle of changing colored light is attuned to the arrivals and departures of trains at the adjacent monorail station.

Govan calls the Los Angeles museum’s show “a little bit of a homecoming” for “a local boy gone good.” Turrell, who was born in L.A. and grew up in Pasadena, is pleased that his work has settled into an exceptionally large chunk of LACMA’s real estate—an entire floor of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum and about a third of the Resnick Pavilion—for an unusually long time. But when reporters and critics question him about his artistic vision, he gets back to his favorite subject: human perception.

“I am very interested in how we perceive because that is how we construct the reality in which we live,” he says. “We all have perception that we have learned. I like to tweak that a little bit, or push you on that. In the Skyspaces, we all know that the sky is blue. We just don’t realize that we give the sky its blueness. We are not very well aware of how much we are part of the making of what we perceive. That’s what I enjoy giving to you. Basically, I have always thought that I use the material, light, to give you perception.”

This summer three major American museums are presenting exhibitions highlighting the achievements of James Turrell ‘65, best known for his large-scale light installations.

LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART

James Turrell: A Retrospective

Through April 6, 2014

The first major Turrell retrospective survey gathers approximately 50 works spanning nearly five decades, including his early geometric light projections, prints and drawings, installations exploring sensory deprivation and seemingly unmodulated fields of colored light, and recent two-dimensional holograms. A section is also devoted to Turrell’s masterwork in process, Roden Crater. www.lacma.org

THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON

James Turrell: The Light Inside

Through Sept. 22, 2013

Titled after the museum’s iconic Turrell permanent installation The Light Inside (1999), and centered on the collection of additional work by the artist at the MFAH, the Houston exhibition makes several of the artist’s installations accessible to the public for the first time. www.mfah.org

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

James Turrell

Through Sept. 25, 2013 Turrell’s first exhibition in a New York museum since 1980 focuses

on the artist’s explorations of perception, light, color and space, with a special focus on the role of site-specificity in his practice. At its core is a major new project that recasts the Guggenheim rotunda as an enormous volume filled with shifting natural and artificial light. www.guggenheim.org

Coolest name for a college band: The Inland Emperors. The group formed last fall, and Wes Haas ’15 and Lee Owens-Oas ’15 came up with the moniker during their Physics with Music class. As Haas explains, they were talking about how they now live in the Inland Empire and wondering whether anyone’s ever thought whether “there’s an emperor of the place” and—voilà—the band, which includes three more Sagehens, had its name. What do they play? “Loud rock music,” says Haas. Gigs so far have mostly been on campus, but with a name like that, we’re sure their reign will someday reach all the way to Riverside.

Coolest name for a college band: The Inland Emperors. The group formed last fall, and Wes Haas ’15 and Lee Owens-Oas ’15 came up with the moniker during their Physics with Music class. As Haas explains, they were talking about how they now live in the Inland Empire and wondering whether anyone’s ever thought whether “there’s an emperor of the place” and—voilà—the band, which includes three more Sagehens, had its name. What do they play? “Loud rock music,” says Haas. Gigs so far have mostly been on campus, but with a name like that, we’re sure their reign will someday reach all the way to Riverside.

On a 70-degree, late-November day, Ian Gallogly ’13 and Rob Ventura ’14 are sitting in the courtyard of the Smith Campus Center and talking hockey.

On a 70-degree, late-November day, Ian Gallogly ’13 and Rob Ventura ’14 are sitting in the courtyard of the Smith Campus Center and talking hockey. The women’s soccer team reached the finals of the SCIAC Tournament for the first time in school history with one of the biggest upsets of the fall season, knocking off top-seeded Cal Lutheran 2-1 in overtime in the semifinals, before losing to Chapman 4-1 in the finals. Julia Dohner ’16 had both goals for the Sagehens in the semifinals, after the team needed to rally late in the regular season to qualify. A 1-0 home win over Redlands on the first career goal from Natalie Barbaresi ’16 put the Sagehens in position to qualify, and a goal from Claire Mueller ’13 in a 1-0 win over La Verne in the season finale put Pomona-Pitzer in the postseason for the second year in a row. Jordan Bryant ’13 and Allie Tao ’14 were named first-team All-SCIAC and earned a spot on the NSCAA All-West Region team as well.

The women’s soccer team reached the finals of the SCIAC Tournament for the first time in school history with one of the biggest upsets of the fall season, knocking off top-seeded Cal Lutheran 2-1 in overtime in the semifinals, before losing to Chapman 4-1 in the finals. Julia Dohner ’16 had both goals for the Sagehens in the semifinals, after the team needed to rally late in the regular season to qualify. A 1-0 home win over Redlands on the first career goal from Natalie Barbaresi ’16 put the Sagehens in position to qualify, and a goal from Claire Mueller ’13 in a 1-0 win over La Verne in the season finale put Pomona-Pitzer in the postseason for the second year in a row. Jordan Bryant ’13 and Allie Tao ’14 were named first-team All-SCIAC and earned a spot on the NSCAA All-West Region team as well.

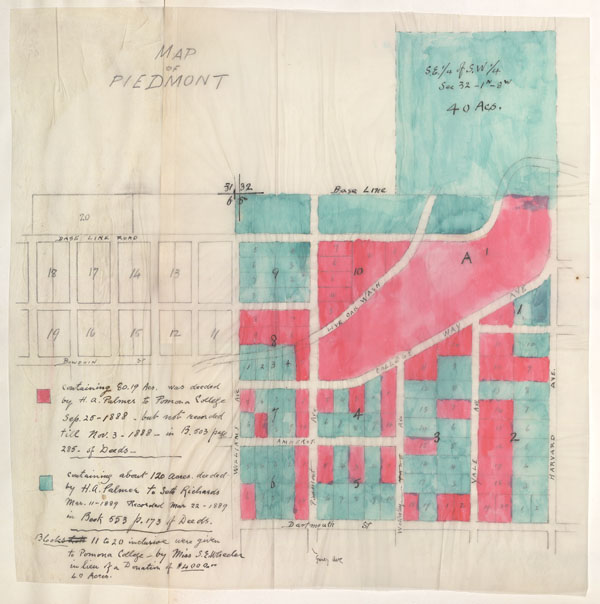

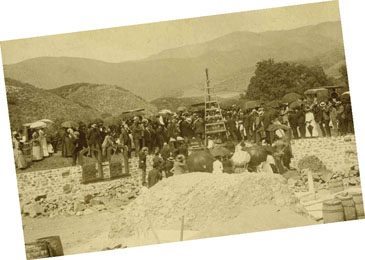

There remained, however, a photo from the September day in 1888 when hundreds of people gathered at the base of the foothills north of Pomona for the cornerstone ceremony. That old black and white helped lead me back to the spot known as Piedmont Mesa and its faint traces of the College’s beginnings.

There remained, however, a photo from the September day in 1888 when hundreds of people gathered at the base of the foothills north of Pomona for the cornerstone ceremony. That old black and white helped lead me back to the spot known as Piedmont Mesa and its faint traces of the College’s beginnings. Even on the little screen, it was easy to line up the old view with the present one, since the hills had changed so little in 125 years. Comparing the two views, it looked to us like the site of the original cornerstone—later relocated—might just lie beneath the 210 Freeway, which today slices through the site.

Even on the little screen, it was easy to line up the old view with the present one, since the hills had changed so little in 125 years. Comparing the two views, it looked to us like the site of the original cornerstone—later relocated—might just lie beneath the 210 Freeway, which today slices through the site.

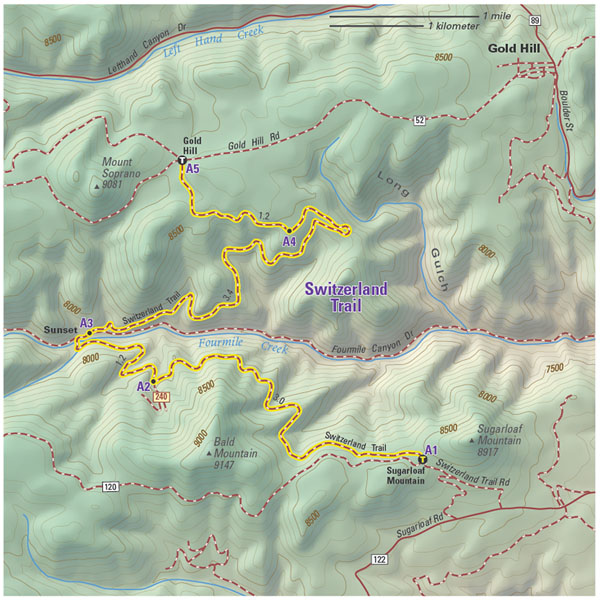

Fortunately, he was able to include some of the historical tidbits—along with 118 maps—in his recently published book, The Mountain Biker’s Guide to Colorado (Fixed Pin Publishing). Hickstein is now a fourth-year grad student at University of Colorado, where he studies how ultrafast lasers can be used to make super-slow-motion movies of chemical reactions. But after a long day in the lab, Hickstein still finds time to ride the trails, sometimes even bringing along his own tome and its trusty maps.

Fortunately, he was able to include some of the historical tidbits—along with 118 maps—in his recently published book, The Mountain Biker’s Guide to Colorado (Fixed Pin Publishing). Hickstein is now a fourth-year grad student at University of Colorado, where he studies how ultrafast lasers can be used to make super-slow-motion movies of chemical reactions. But after a long day in the lab, Hickstein still finds time to ride the trails, sometimes even bringing along his own tome and its trusty maps.

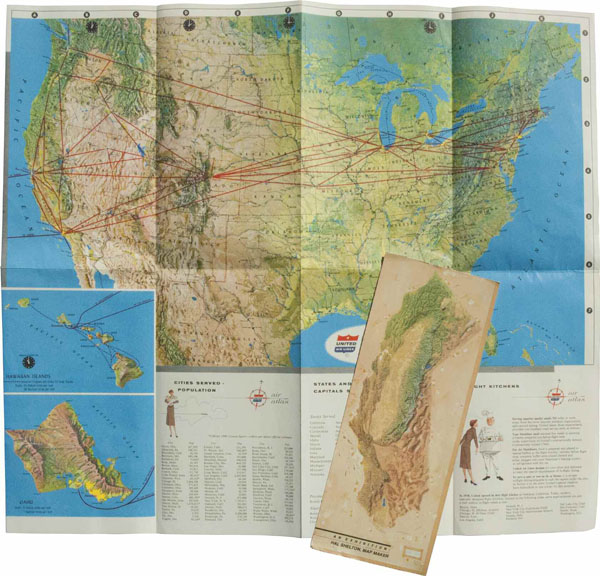

If the natural color concept seems straightforward—forests are green, deserts are brown— the execution required patience, skill and considerable expense. Decades before satellite imagery was widely available, Jeppesen hired academic geographers to gather the data, which was etched into zinc plates about two to three feet in diameter. Working on an inch at a time, Shelton then painstakingly painted on the landscape features along with shaded relief to show elevation. His artistry yielded “realistic picture maps that astound the cartographic world,” as The New York Times gushed in 1954.

If the natural color concept seems straightforward—forests are green, deserts are brown— the execution required patience, skill and considerable expense. Decades before satellite imagery was widely available, Jeppesen hired academic geographers to gather the data, which was etched into zinc plates about two to three feet in diameter. Working on an inch at a time, Shelton then painstakingly painted on the landscape features along with shaded relief to show elevation. His artistry yielded “realistic picture maps that astound the cartographic world,” as The New York Times gushed in 1954.