The odds were not in his favor. Guy Stevens ’13 didn’t need his double major in math and economics to understand that. His right arm made him a good enough baseball player to pitch for the Pomona-Pitzer Sagehens, but it was not going to get him to the major leagues.

About 450,000 youngsters play Little League Baseball each year. Some go on to play in high school and almost 32,000 played in college for National Collegiate Athletic Association teams last year. A fraction of those high school and college players are drafted, destined for long bus rides and budget hotels in the minor leagues. They are all fighting for one of 750 jobs in the big leagues. In the history of Pomona College, precisely one player, Harry Kingman, has made it, playing in four games for the New York Yankees in 1914.

Stevens already made it to the majors last summer with the New York Mets and is back again this season with the Kansas City Royals. His bankable talent is with a computer, not his fastball, and he is taking the multiple internship route to try to land a coveted job doing statistical analysis in the front office of a major league team.

“I was really into baseball, but didn’t know it was a feasible career path,” Stevens says. “Now I’m going to see how far I can take this, see if I can do this.”

Stevens, 21, is riding the wave of a sea change in professional baseball in the decade since the publication of the 2003 book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game—later a movie starring Brad Pitt—about the Oakland Athletics’ use of statistical analysis to try to maximize a low payroll. A game traditionally run by executives who were either former professional players or scouts who spent years in the stands with a stopwatch and a radar gun is increasingly dotted with Ivy Leaguers, academics and young people with math or finance backgrounds as the 30 major league teams—some of them billion-dollar businesses—try to mine the avalanche of available data.

“There aren’t many jobs,” says Adam Fisher, a Harvard graduate who is director of baseball operations for the Mets and supervised Stevens last summer after starting his career as an intern himself. “But I think he has the ability. I would bet on him, yeah. “He kind of comes at it with a unique blend of skills and talents, having played college baseball and having a real strong math and stats background. Generally, you see one or the other.”

GREGARIOUS AND HANDSOME despite his wonkish affection for stats, Stevens grew up an Oakland A’s fan in the East Bay town of Lafayette and played baseball at Campolindo High School in Moraga. His father is an investment portfolio manager in San Francisco, and his mother once worked in finance as well.

“I thought I’d do something like that. I knew I was good with numbers,” he says. His early forays into the numbers behind the game started as a teenager.

“I read Moneyball pretty soon after it came out. My freshman year in high school, I started playing fantasy baseball, and I was playing with some of my friends on the baseball team,” says Stevens, noting that those teammates were not quite as numbers-savvy. “So I thought, ‘I’m going to see what I can do to get an edge,’ and I really started looking at his stuff and just got caught up in it.”

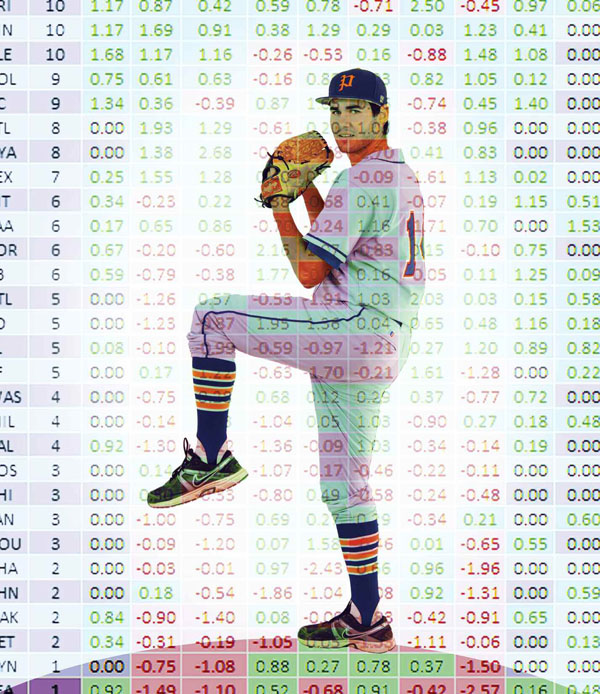

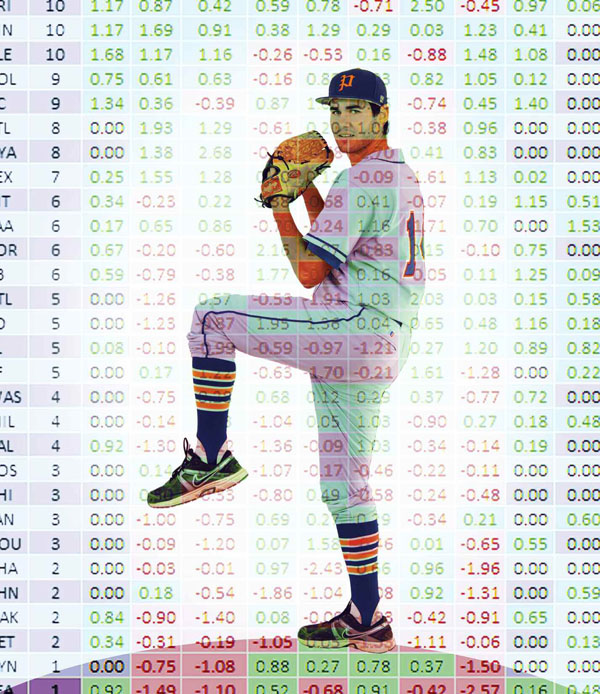

Statistics always have been important in baseball, but in recent decades the familiar stats such as batting average, ERA (earned-run average) and RBI (runs batted in) have been supplemented by an alphabet soup of acronyms, all trying to quantify aspects of the game. There’s WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) WAR (wins above replacement) BABIP (batting average on balls in play) and FIP (fielding-independent pitching) and those are just some of the more well-known ones.

Statistics always have been important in baseball, but in recent decades the familiar stats such as batting average, ERA (earned-run average) and RBI (runs batted in) have been supplemented by an alphabet soup of acronyms, all trying to quantify aspects of the game. There’s WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) WAR (wins above replacement) BABIP (batting average on balls in play) and FIP (fielding-independent pitching) and those are just some of the more well-known ones.

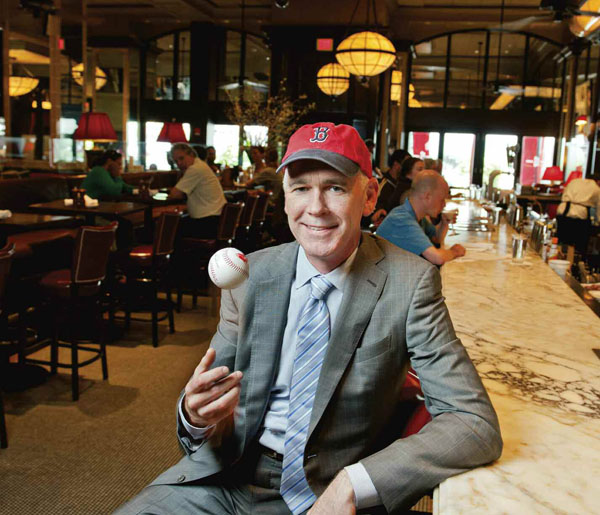

The challenge is to sift through the gargantuan amount of data and shape it in useful ways—and most important, to try to predict performance and assess the monetary value of a player’s skill. The A’s, for example, concluded a stat such as on-base percentage, which includes walks, might be as important as a traditional stat like batting average in determining a player’s value to a team. The Boston Red Sox used some of the same principles in putting together the teams that won the 2004 and 2007 World Series with a brain trust that was led by Yale graduate Theo Epstein and included advisor Bill James, an influential figure who has written about statistics since the 1970s.

Today, technological advances help fuel the stats craze. Leaning over his MacBook Pro in an empty office in Millikan Laboratory, the 6-foot-2 Stevens stares at a screen full of columns of stats and mostly indecipherable abbreviations. To his trained eye, flesh-and-blood players and games that were played seasons ago appear.

Since 2006, Major League Baseball has used a system that positions cameras to track the speed and movement of every pitch thrown in a game, giving statisticians a deep resource of information. So does a site called Retrosheet.org, which has digitally recorded the play-by-play accounts of most major league games since 1956.

To illustrate, Stevens called up a 1997 game between the Angels and Boston Red Sox in Anaheim and showed that a first-inning pitch against a right-handed batter was fouled back. That sort of detailed information can be used to identify tendencies of certain batters and pitchers that, when put together, can give clues to a player’s value to a particular team. “Sites like this make it possible for people outside front offices to do analytics,” Stevens says.

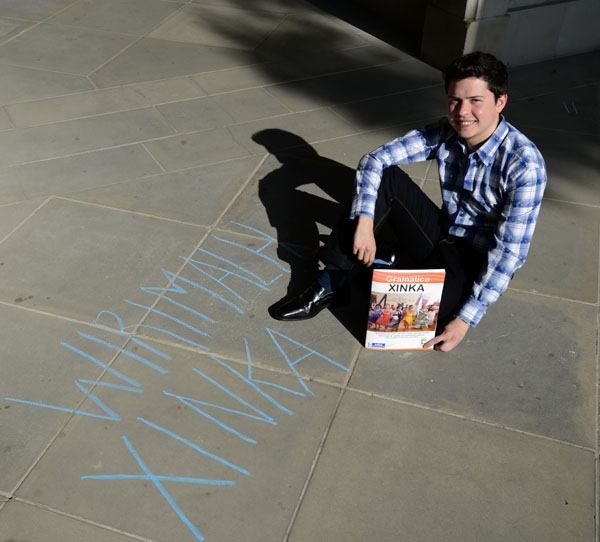

Stevens did just that at Pomona, where his time on the field was limited by injuries until the 2012 season when he emerged as the team’s closer. (He also played a stint on the national team of Israel, where his mother grew up. See story on page 28.) So Stevens huddled in his room in Lawry Court and dug deeper into the world of stats. Eventually, he created a blog, DormRoomGM.com that impressed major league executives.

“I’d do a lot of hypothetical, ‘Could Team X improve their roster by trading Player A for Player B?’” Stevens recalls. “That was mostly for fun because those trades are so unlikely to happen.”

IT WAS DURING THE SUMMER before his junior year that Stevens became focused on his track toward more sophisticated work in baseball analytics —also sometimes called sabermetrics, taking the name from the Society for American Baseball Research. In Claremont for the summer to work on an ill-defined academic project involving minor league baseball stats, he kept running into Gabe Chandler, a Pomona associate professor of statistics who also helps coach the baseball team.

Chandler helped Stevens focus the project, and the two used a statistical method called random forests to try to determine which qualities in minor league players predict they will progress to the majors. The work grew into a scholarly article published in the Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports that the pair coauthored. The study got the attention of Wired, which ran a story on its website.

“He had collected some interesting data, data nobody really had,” Chandler says. “Everybody and their sister has analyzed major league data, so that’s not a new problem. But for whatever reason, nobody had really looked at the minor leagues. … But he probably knew that, because he thinks about this so much.”

Among their conclusions: Strikeouts in rookie ball, the lowest level of professional baseball, bode poorly for success. That might seem obvious, but the same didn’t hold true at higher levels of the minor leagues.

“It really only shows up in rookie ball,” Chandler says. “Because usually the people that get sent to rookie ball are high school players. College players usually start in low-A ball. You see a high school kid and they’re not facing quality pitching, so somehow you’re drafting these kids based off of, I don’t know what—athleticism or ‘tools.’ But you’ve never seen these kids try to hit a 95-mile-an-hour fastball. So you draft them and give them a lot of money and then send them to rookie ball, where they’re facing the few high school pitchers that can throw 95. And if they can still put the bat on the ball, then that’s a good sign. And if they can’t.…”

That’s the sort of insight teams that hire statisticians are looking for—anything that can give them an edge in evaluating talent to predict performance and the probability of winning on the field.

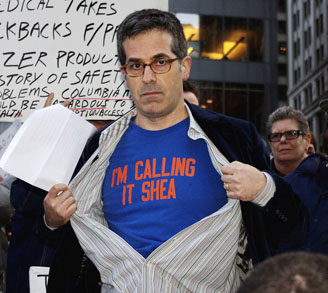

Chandler made what turned out to be a key connection for Stevens at a conference when he met Ben Baumer, now a visiting assistant math professor at Smith College in Northampton, Mass., but previously the statistical analyst for the Mets for nine seasons. By last summer, Baumer and Stevens were both working for the Mets.

“Very few jobs doing this existed 10 years ago,” says Baumer, who collaborated with noted sports author and economist Andrew Zimbalist to write a book, The Sabermetric Revolution: Assessing the Growth of Analytics in Baseball, to be published in December.

“I got a job with the Mets in 2004 and they had never had someone doing that before. Things have changed quite dramatically,” Baumer says. “There are only about five teams that aren’t doing it now, and the Rays (Tampa Bay’s major league team) have about eight people dedicated to this, several of them with master’s degrees, and a programmer.

“Guy did a good job for us,” Baumer says. “It’s hard to speculate, but I think he’s definitely put himself in a good position with a strong quantitative background, playing college baseball and the internships.”

While working for the Mets, Stevens learned more data an programming skills using SQL, or Structured Query Language. His duties were as varied as summarizing the player reports sent in by minor league managers each day, using statistics to analyze how to put together a major league bullpen and, at some games, identifying pitches for the stadium scoreboard display—fastball, changeup, curve, even R. A. Dickey’s knuckleballs. After nervously working his first game charting pitches after being teased that fans would boo if he got one wrong, Stevens walked into an office for his review.

“One of my bosses is sitting there and he’s got a piece of paper in front of him and he was like, ‘Guy, so, you got about 82 percent of the pitches right, which is pretty low.’ And I was, ‘Oh, God,’ and super nervous. But he was just holding a [random] piece of paper. They didn’t keep track.”

The Royals saw Stevens’ experience with the Mets, read his blog and were impressed: After hiring him for a six-month internship starting this summer that he hopes might grow into a regular job, the club asked him to take down his blog, considering it proprietary information. He works for Mike Groopman, the Royals’ director of baseball analytics, a graduate of Columbia University who broke into the game with internships with the Cincinnati Reds and the Mets.

STEVENS’ SAGEHEN PITCHING CAREER ended with a loss in the NCAA Division III regionals a week before his May graduation from Pomona. He pitched a final time, gutting through the pain of an elbow injury that cost him much of his senior season.

He understands that statistics, too, have their limits. For example, analysts have struggled to quantify fielding ability, though new technology is coming. “That’s something I’ll hopefully get to work on in Kansas City,” Stevens says.

Or what about deception, he suggested, such as a pitcher’s ability to hide the ball and disguise a pitch? Or the quality of being a clutch player, or a good teammate whose work ethic sets an example?

“I think the next big edge a team could get would be either if they’re a little bit better at preventing players from being injured, or just knowing who’s an injury risk and either getting rid of them or just not acquiring them in the first place,” Stevens says, knowing that with his history of arm problems, he would be considered such a risk.

Armed with his degree and experience, he will take a swing at the big leagues, understanding how competitive a field it is and knowing there are only 30 of the holy grail of front-office jobs, general manager. If not baseball, Stevens said, maybe he will turn to a career in finance.

“I’d really like to be a GM,” he said. “That’s the dream. I mean, the dream used to be to play, but I’m realistic.”

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood.

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood. In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”

In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”

With adulthood, though, my life shifted. Shoeboxes full of trading cards were tucked away. No more family pilgrimages to Chavez Ravine. My interest in Major League Baseball faded. By the ’90s, I would have been hard-pressed to name more than a player or two on my once-favorite team.

With adulthood, though, my life shifted. Shoeboxes full of trading cards were tucked away. No more family pilgrimages to Chavez Ravine. My interest in Major League Baseball faded. By the ’90s, I would have been hard-pressed to name more than a player or two on my once-favorite team. But even as the halos won the series, I couldn’t get past their past. Where was the proud history, the tried-and-true tradition? L.A.-area bookstore shelves are laden with Dodgers tomes. The Angels are literary laggards by comparison. One key exception, Ross Newhan’s The Anaheim Angels: A Complete History, offers a first chapter titled “The Parade of Agony,” aptly summarizing the team’s early decades. I wasn’t ready to completely ditch the Dodgers.

But even as the halos won the series, I couldn’t get past their past. Where was the proud history, the tried-and-true tradition? L.A.-area bookstore shelves are laden with Dodgers tomes. The Angels are literary laggards by comparison. One key exception, Ross Newhan’s The Anaheim Angels: A Complete History, offers a first chapter titled “The Parade of Agony,” aptly summarizing the team’s early decades. I wasn’t ready to completely ditch the Dodgers.

Statistics always have been important in baseball, but in recent decades the familiar stats such as batting average, ERA (earned-run average) and RBI (runs batted in) have been supplemented by an alphabet soup of acronyms, all trying to quantify aspects of the game. There’s WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) WAR (wins above replacement) BABIP (batting average on balls in play) and FIP (fielding-independent pitching) and those are just some of the more well-known ones.

Statistics always have been important in baseball, but in recent decades the familiar stats such as batting average, ERA (earned-run average) and RBI (runs batted in) have been supplemented by an alphabet soup of acronyms, all trying to quantify aspects of the game. There’s WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) WAR (wins above replacement) BABIP (batting average on balls in play) and FIP (fielding-independent pitching) and those are just some of the more well-known ones.