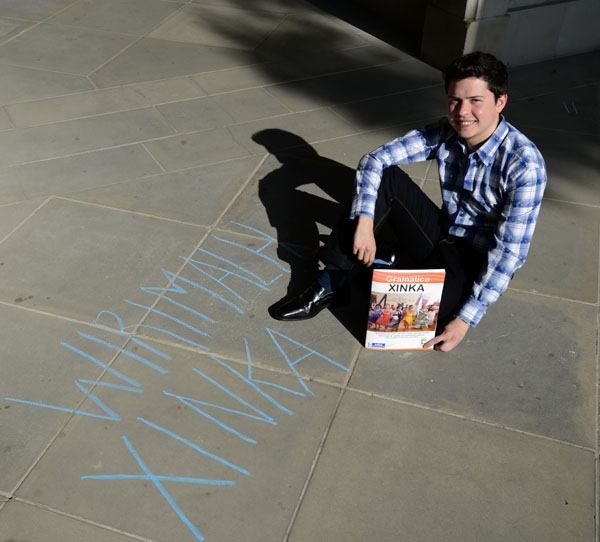

In today’s session of Professor Hung Thai’s seminar on Immigration and the New Second Generation, the discussion focuses on whether schools in the U.S. provide opportunity for the children of recent immigrants or, because of the prevalence of tracking—grouping together students based on test scores or perceived ability—schools create even bigger hurdles that have negative consequences long after students graduate and enter the workforce.

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

Anissa: What was the philosophy behind tracking, what made someone think it was a good idea?

Thai: Tracking started as a solution to the immigrant problem. The first mass wave of immigration to this country occurred from the 1890s to the 1920s. With the influx of large numbers of immigrants, educators had to figure out ways to stratify the native populations against the immigrant populations. They did that, presumably, based on ability. How many of you went to schools that had tracking?

Sophia: I went to Claremont High, and it didn’t have tracking.

Thai: You didn’t have tracking? How about AP though, that’s another form of tracking.

LaFaye: We had three different programs in our high school in Chicago. The top floor was for the medical students; the second floor for Phi Beta or the law students and the first floor for regular students. At my school they would give out literacy tests and would separate those who scored above from the others who didn’t score as well.

Thai: There are essentially two ways of tracking students, and both systems are problematic on multiple levels. The main way is based on test scores. The other, which is actually much more prevalent that most people think, is the subjective evaluations of teachers on the perceived abilities of students. Some people argue that tests themselves don’t evaluate a student’s lifelong learning and capacity. The second argument about teacher’s evaluations is that there is something about schools, particularly in more middle class schools, where teachers subjectively evaluate students on the standards of middle class values and the standards of learning that take place in private homes. Which is why we know tracking tends to be racialized and classed, with poorer students tracked in the lower levels much more.

Electra: What are examples of middle class values?

Thai: Perhaps the most well-known book that makes this argument is Unequal Childhoods by Annette Lareau in which she argues that children who grow up in middle class families tend to be more assertive and tend to question authority. But children who come from poorer families or minority families tend to question less, to take orders more.

In Schooling in Capitalist America, Bowles and Gintis argue that one of the major ways schools reinforce inequalities is that poor schools essentially function as a site for producing a reserved army of labor for the American labor market; that tracking systems train the wealthy to work in jobs that allow them to have more authority, more managerial positions and, at the same time, condition the poor to take on jobs that tend to be more unskilled labor.

Mabelle: This whole idea of mobility over generations reminded me of what Vivian Louie said at the end of her book about immigrant parents and their pessimism about assimilation. That they themselves couldn’t reach a certain level, but because they have the sheer hope that the American dream is worth it for their children, they can take on anything, which is inspiring, but also scary.

Thai: Most people presume that the immigrant success story is linked to one generation. Louie says that is not actually the reality. She points out that it takes at least four generations for the students she writes about to experience long-range upward mobility. Americans tend to believe that we have longer-range patterns of mobility than we do, when in fact, when compared to Western Europe, our patterns of mobility are shorter ranged.

Tim: If one of the major reasons these immigrant families come to the U.S. is to give their kids more opportunities, the more interesting question is: is it morally, is it socially OK for them to come here with that expectation? Is that how immigration works in America? Parents justify the inequality they face because they think their kids are going to have equal opportunity because this is America. But is that actually the case?

The Professor:

At Pomona since 2001, Hung Cam Thai is an associate professor of sociology and Asian American Studies. Thai earned his Ph.D. in sociology from U.C. Berkeley and is the author of the book For Better or For Worse: Vietnamese International Marriages in the New Global Economy and the forthcoming InsufficientFunds: The Culture of Money in Low Wage Transnational Families Last year, he was awarded the Outstanding Teaching Award by the Asian American Section of the American Sociological Association.

The Course:

Immigration and the New Second Generation focuses on the body of immigration research that gives attention to age-related experiences, paying particular attention to young adults coming of age as they negotiate the major social institutions of American life, such the labor market, family, work and schooling.

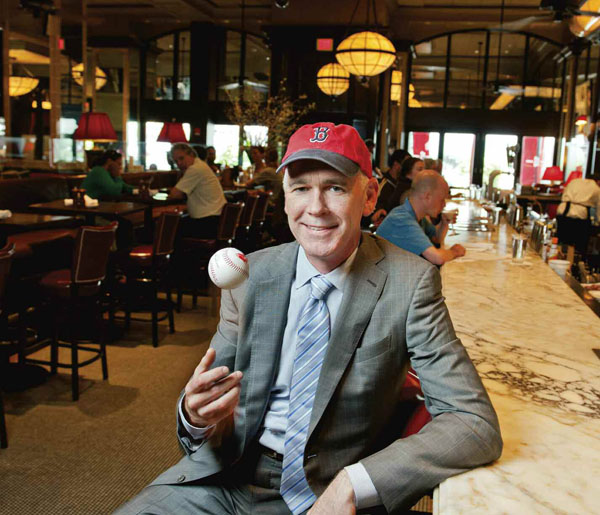

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood.

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood. In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”

In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”

With adulthood, though, my life shifted. Shoeboxes full of trading cards were tucked away. No more family pilgrimages to Chavez Ravine. My interest in Major League Baseball faded. By the ’90s, I would have been hard-pressed to name more than a player or two on my once-favorite team.

With adulthood, though, my life shifted. Shoeboxes full of trading cards were tucked away. No more family pilgrimages to Chavez Ravine. My interest in Major League Baseball faded. By the ’90s, I would have been hard-pressed to name more than a player or two on my once-favorite team. But even as the halos won the series, I couldn’t get past their past. Where was the proud history, the tried-and-true tradition? L.A.-area bookstore shelves are laden with Dodgers tomes. The Angels are literary laggards by comparison. One key exception, Ross Newhan’s The Anaheim Angels: A Complete History, offers a first chapter titled “The Parade of Agony,” aptly summarizing the team’s early decades. I wasn’t ready to completely ditch the Dodgers.

But even as the halos won the series, I couldn’t get past their past. Where was the proud history, the tried-and-true tradition? L.A.-area bookstore shelves are laden with Dodgers tomes. The Angels are literary laggards by comparison. One key exception, Ross Newhan’s The Anaheim Angels: A Complete History, offers a first chapter titled “The Parade of Agony,” aptly summarizing the team’s early decades. I wasn’t ready to completely ditch the Dodgers.