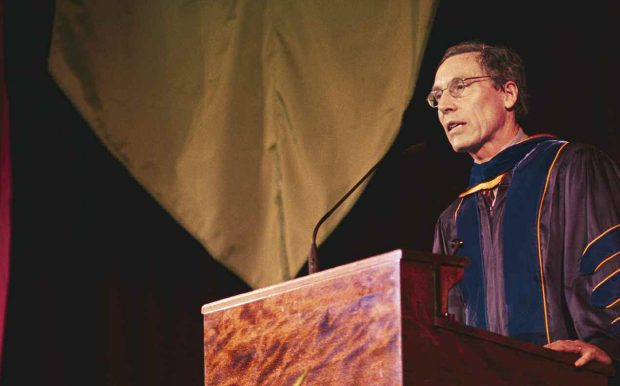

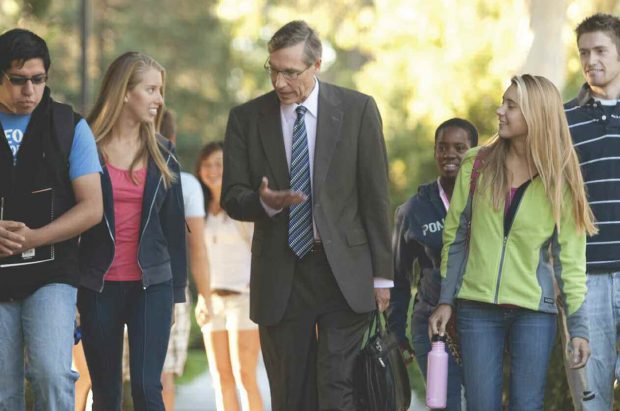

PHYSICS: Professor of Physics David Tanenbaum

Organic Solar

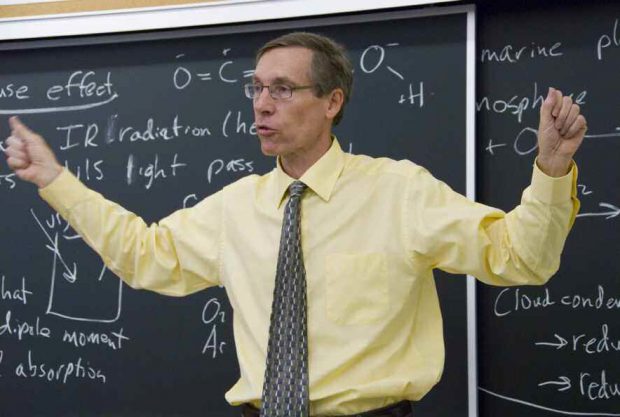

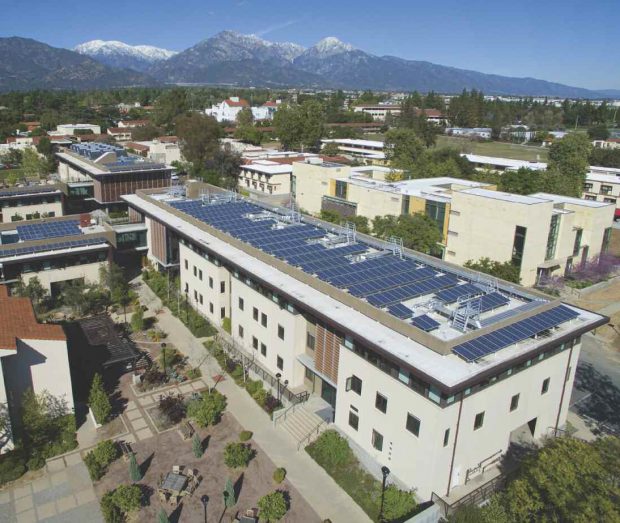

What was once a rare sight is now becoming more common: solar panels on the roofs of homes across the country. While solar technology has improved and is seeing exponential growth as an industry, Pomona College Professor of Physics David Tanenbaum notes that there are still a few factors limiting production at a mass scale globally. Tanenbaum and his student researchers are working to improve this by focusing on one important factor: the cost of the materials used in producing solar cell panels.

Tanenbaum explains that today’s solar panels, like microchips, are made with silicon, which requires a fairly expensive production process because of factors such as the need for high-temperature processing of high-purity materials. In building solar panels, he says, the difference in cost between silicon and less expensive organic materials is like the cost difference between manufacturing a flat-screen TV and printing ink on paper. Imagine, he says, trying to cover the globe with expensive flat-screen televisions; that’s where solar cell technology is today. Now imagine covering the globe with printed paper and how much cheaper and easier that would be. That’s where he wants to see solar technology go.

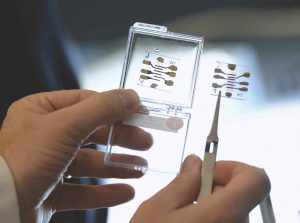

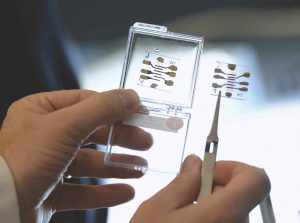

To this end, Tanenbaum and his students are making organic solar cells using chemicals like poly(3-hexylthiophene), P3HT for short, or [6,6]-phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester, known as PCBM. They are experimenting with differing materials and processing techniques to make the cells.

“The main thing we want to get out of solar technology is a way to produce electricity. Everyone would benefit from electricity that is carbon neutral, and solar cells require no fuel stock: no gasoline, diesel or nuclear pellets. The sun is out there whether we take advantage of it or not,” he says.

When it comes to solar cell technology, there are three main attributes: efficiency (how good the device is at converting sunlight into energy), production cost (how much it costs to produce cells and panels), and lifetime (how long the device will last).

Current solar technology has good efficiency and a long lifetime, but the challenge still lies in the cost, he says.

“The idea is to bring the cost way down, even if it means the efficiency and lifetime is not so good,” he says. “The efficiency of the solar cell is maybe not perfect, but the reality is there’s not a lot of waste. When you burn diesel fuel or natural gas to make electricity, you produce a lot of waste heat. You’re not wasting anything from the sun, just using a little bit for your advantage. The low cost allows us to displace natural gas, coal, all those things that have issues.

“In the grand scheme of things, we’d like to produce electricity at a low cost and put electricity in isolated places relatively easily. In the U.S. everyone is connected to the electricity grid, but not everyone in the world is. You can’t build a nuclear power plant for a small amount of people, but solar energy can grow with the population.”

Tanenbaum has been working on this particular type of solar cell technology research for about eight years and has had students in the laboratory helping since the beginning.

Sabrina Li ’17, a physics major, and Meily Wu Fung ’18, an environmental analysis major, were summer lab researchers through the Summer Undergraduate Research Program (SURP).

Li has been working with Tanenbaum since her first year at Pomona and is planning a senior project that encapsulates what she’s learned in the lab thus far. “I’m looking at organic solar cells. They’re organic instead of silicon, and I’m looking at trying to optimize efficiency and lifetime.” Li experiments with different materials and processing techniques to make the cells.

This was Wu Fung’s first summer doing research at Pomona. She’s working on testing the aging of cells over time, using cells created over the past three years in the lab that are still working today. “At the end of the day, when we’re done making the cells, it’s really gratifying to measure them and see what’s come of it.”

Tanenbaum is on sabbatical for the 2016–17 academic year, continuing his research on solar cell technology at the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

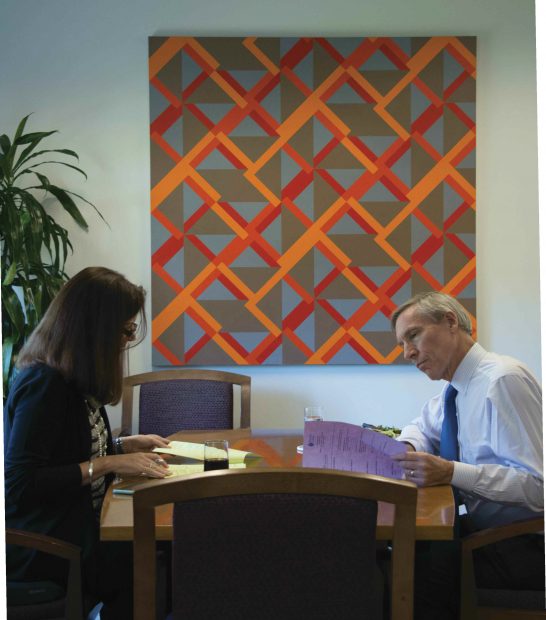

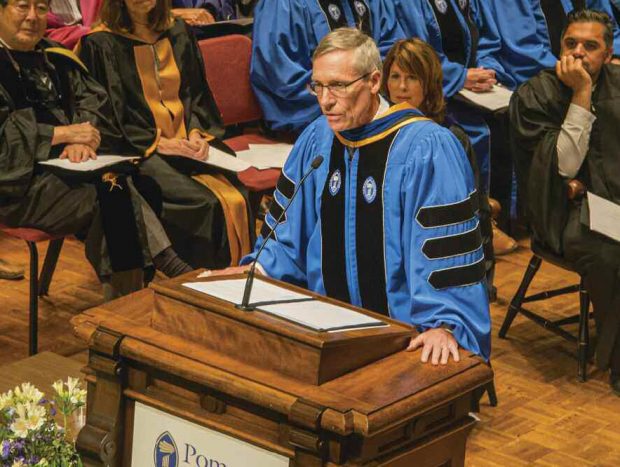

PSYCHOLOGY: Assistant Professor of Psychology Adam Pearson

Not Your Average Online Quiz

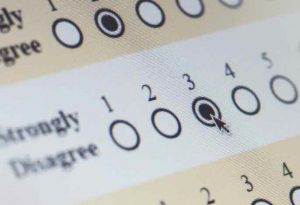

It’s not your typical online poll—the type you find on BuzzFeed to determine which Hogwarts house you’d be sorted into, or what your Game of Thrones name would be. Assistant Professor of Psychology Adam Pearson, along with Princeton social psychologist Sander van der Linden, have developed a series of online surveys for Time magazine to see what Americans think about issues like climate change, gun safety and genetically modified food and how in touch they are with others’ beliefs on these issues.

It’s not your typical online poll—the type you find on BuzzFeed to determine which Hogwarts house you’d be sorted into, or what your Game of Thrones name would be. Assistant Professor of Psychology Adam Pearson, along with Princeton social psychologist Sander van der Linden, have developed a series of online surveys for Time magazine to see what Americans think about issues like climate change, gun safety and genetically modified food and how in touch they are with others’ beliefs on these issues.

The first survey was on how different groups feel about gun ownership. It was to be followed by surveys on issues like climate change, evolution, GMO food consumption, vaccination and gun safety.

At the end of each survey, the reader has a chance to see if he or she has accurately assessed how other people feel about the same subjects. The results, says Pearson, can be very surprising.

“Many seemingly intractable social problems come down to a deceptively simple, but quite powerful truth: Social perceptions matter. As adults, we may like to think that peer pressure is something that only kids are susceptible to—that we come to hold the views that we do through logic and reason—but decades of research in social psychology suggest otherwise,” he says.

“We thought this would be a terrific opportunity to test and expand on a well-known set of social psychological effects with a large and diverse sample of Americans,” says Pearson of the partnership with Time. “We know that one of the best predictors of how you’ll feel about an issue is what you think others think about the issue,” he says. For example, people are more inclined to believe in human-caused climate change when they perceive that there is scientific consensus on the subject, regardless of which political party they align with.

“These meta-perceptions or meta-beliefs—what we think others think—matter,” he adds.

One way this shows itself is what is known as the false consensus effect. “We tend to (and often falsely) assume others hold the same beliefs that we do,” says Pearson. “Another effect is called pluralistic ignorance—a tendency to perceive that my private beliefs don’t align with those around me. Both types of perceptions can influence how we behave. If we want to build consensus on issues that are important to us, we first need to accurately understand others’ views. This is especially true for building consensus on contentious and politicized issues, from gun safety to the foods we consume.”

The findings will be used by Time and shared widely after the surveys are concluded. Pearson and van der Linden also plan to use their findings in their research to broaden our understanding of factors that shape public opinion on these issues.

—Carla Guerrero ‘06

It’s not your typical online poll—the type you find on BuzzFeed to determine which Hogwarts house you’d be sorted into, or what your Game of Thrones name would be. Assistant Professor of Psychology Adam Pearson, along with Princeton social psychologist Sander van der Linden, have developed a series of online surveys for Time magazine to see what Americans think about issues like climate change, gun safety and genetically modified food and how in touch they are with others’ beliefs on these issues.

It’s not your typical online poll—the type you find on BuzzFeed to determine which Hogwarts house you’d be sorted into, or what your Game of Thrones name would be. Assistant Professor of Psychology Adam Pearson, along with Princeton social psychologist Sander van der Linden, have developed a series of online surveys for Time magazine to see what Americans think about issues like climate change, gun safety and genetically modified food and how in touch they are with others’ beliefs on these issues.

Thank you for the faith focus of your summer 2016 issue. It is good to know that, just as in my day, people of faith are being helped by their Pomona education to deepen and integrate their received religious heritages into modern worldviews that will enable them to live creative and fruitful lives.

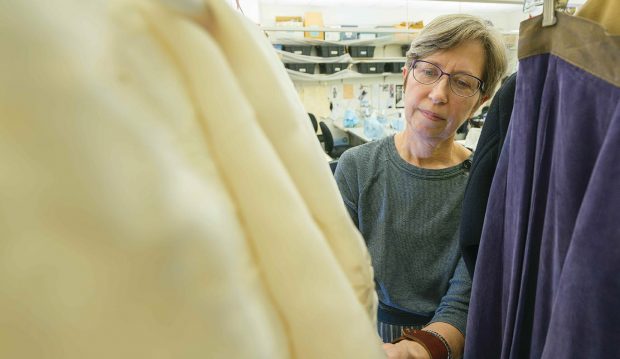

Thank you for the faith focus of your summer 2016 issue. It is good to know that, just as in my day, people of faith are being helped by their Pomona education to deepen and integrate their received religious heritages into modern worldviews that will enable them to live creative and fruitful lives. Suzanne Schultz Reed’s classroom is not your typical seminar room. Upon entering, visitors are immediately greeted by a costume rack boasting dozens of hangers and garments in various states of completion. Long project tables dominate the open space, ringed by smaller workstations furnished with bright white sewing machines and strips of fabric. The walls are covered in color sketches of period dresses and men’s breeches; visible in the supply cabinets are buckets of buttons and thread and pincushions. Today is Wednesday and the room is uncharacteristically quiet, humming only with the sound of sewing machines and soft conversation between Schultz Reed and her student worker, Amy Griffin (Scripps ’18). “On Fridays, I have six students working in the shop,” Schultz Reed explains. “It’s very social. Everybody’s chatting, everybody’s doing something, music is on. And—” here she grins wickedly—“I bring brownies on Fridays.”

Suzanne Schultz Reed’s classroom is not your typical seminar room. Upon entering, visitors are immediately greeted by a costume rack boasting dozens of hangers and garments in various states of completion. Long project tables dominate the open space, ringed by smaller workstations furnished with bright white sewing machines and strips of fabric. The walls are covered in color sketches of period dresses and men’s breeches; visible in the supply cabinets are buckets of buttons and thread and pincushions. Today is Wednesday and the room is uncharacteristically quiet, humming only with the sound of sewing machines and soft conversation between Schultz Reed and her student worker, Amy Griffin (Scripps ’18). “On Fridays, I have six students working in the shop,” Schultz Reed explains. “It’s very social. Everybody’s chatting, everybody’s doing something, music is on. And—” here she grins wickedly—“I bring brownies on Fridays.”