Remembering Martha

If there was one person more than any other who personified what made my experience of Pomona extraordinary, it was Professor Martha Andresen. The brilliance of her intellect was matched by the openness of her heart, and she instilled in me a love of literature that remains alive after more than three decades. I know that I am far from unique in that regard; a number of my classmates who have gone into teaching have spoken of drawing on her example years later. She challenged her students in the best possible way, confronting the flaws and unexamined assumptions in our thinking not to make us feel inferior but to push us to become the better readers, writers and thinkers she believed we could be.

I had the great good fortune of continuing a friendship with Professor Andresen long after I had graduated, corresponding about our lives, art, politics, and most of all writing. We would discuss the books we had recommended to each other, explicating what a particular writer had achieved or failed to achieve. This was never dull academic pontificating, at least on her end; everything she wrote burned with her love of the written word. I have kept every one of those letters from her, and I cherish them.

Pomona will of course go on, with other talented and dedicated professors to lead it into the future, but it will never be the same. Martha Andresen will never be replaced.

—Eric Meyer ’87

Lake Oswego, OR

Wilds of L.A.

Thanks to Char Miller for his review of the natural systems that have shaped Los Angeles (“The Wilds of L.A.,” PCM Spring 2018). But I think he’s misreading the city when he calls it “concretized and controlled” and claims that it’s “nearly impossible to locate nature” in Los Angeles, except in the earthquakes, fires and floods that he describes in almost apocalyptic tones.

In contrast to many large cities, wildlife and nature are a wonderful, unavoidable part of everyday life in Los Angeles. At our home just two miles north of Downtown L.A., we are frequently visited by coyotes, bobcats, possums, raccoons, skunks and snakes. Birds of prey like red-tailed hawks and screech owls share the trees with woodpeckers, finches, warblers and hummingbirds.

I was especially chagrined that Prof. Miller dismisses the Los Angeles River as an “inverted freeway.” The channelized River is indeed a concrete ditch for much of its 52-mile run, but it is also a habitat for much wildlife, especially in the three “soft-bottom” sections of the river (the Sepulveda Basin, the Glendale Narrows, and the Long Beach Estuary). I recently published a novel set on the L.A. River (The Ballad of Huck & Miguel), and the fugitives in the book encounter many of the same animals that I’ve encountered down there, including herons, egrets, turtles, fish and snakes.

What’s more, millions of LA residents live less than an hour away from mountain waterfalls, desert oases and ocean tide pools. For nature lovers who also want access to the cultural diversity (and economic opportunity) of a major urban metropolis, there is no better place to be than Los Angeles.

—Tim DeRoche ‘92

Los Angeles, CA

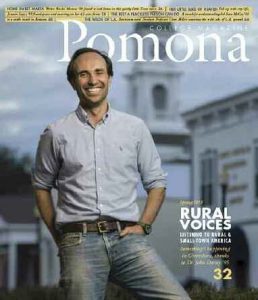

A Rural Voice

A Rural Voice

As a longtime “Rural Voice” from Beaver Dam, Wis., I was especially interested in Mark Wood’s piece on Rachel Monroe ’06 and Marfa, Texas, because I had just been reading Possibilities by Patricia Vigderman. In the chapter “Sebald in Starbucks” she writes about sitting in Starbucks in Marfa and reading W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz. She explains how Marfa got its name: In 1881, a Russian woman came with her husband, a railroad overseer, to an unnamed whistle stop. She was reading a novel published the previous year, The Brothers Karamazov, in which Dostoevsky gave the name Marfa to the Karamazov family servant—and the unnamed town in Texas got its name. The essay is delightful, as is the book by Vigderman.

—Caroline Burrow Jones ’55

Pasadena, CA

Dwyer Passing

Thank you, PCM, for publishing news of the passing of former Pomona College Assistant Professor of History John Dwyer. He served at Pomona for only a few years, but the quality of that service was unmatched in my experience. I remain grateful beyond words for his friendship and guidance, for his love of history and Africa and for his wonderful family. Saturday mornings will always bring memories of the Metropolitan Opera broadcast, accompanied by a proper pot of tea. Thank you, Mr. Dwyer, for everything.

—David Beales ’73

Elk Grove, CA

A Barnett Fan

Okay, maybe the good part of being a children’s author is that Mac Barnett’s (’04) kid audience doesn’t “fanboy” over him…but the adults reading his books definitely do! I was so psyched to open the Spring 2018 issue to “Ideas That Feel Alive.” We are HUGE fans of his work in our family, and we read one of his books with our 2½-year-old Lyra almost every day. We particularly love his collaborations with illustrator Jon Klassen—Extra Yarn and The Wolf, The Duck & The Mouse are our most beloved favorites. We’d actually just bought Triangle for Greg Conroy’s (Pomona ‘00) son Malcolm’s third birthday on the same day the PCM arrived in the mail! It’s super refreshing to read kids’ books that are quirky and smart: Barnett doesn’t talk down to kids or dumb down his stories, even when they’re a little dark or offbeat (in the best way possible). We can’t wait to keep reading everything he writes!

—Chelsea Morse ‘02

Astoria, NY

Kudos for PCM

Pomona College Magazine continues to be readable, relevant and enlightening, thanks to your creativity and hard work. We look forward to each issue and read it cover to cover.

—Bonnie Home ’62 and

DeForrest Home ’61

San Jose, CA

Alumni, parents and friends are invited to email letters to pcm@pomona.edu or “snail-mail” them to Pomona College Magazine, 550 North College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711. Letters may be edited for length, style and clarity.

Pomona College’s new vice president for student affairs and dean of students, Avis E. Hinkson, brings more than three decades of higher education experience in areas ranging from residential life to student recruitment to undergraduate advising. Her new role, which she began on Aug. 1, marks her return to Pomona College, where she was an associate dean of admissions from 1990 to 1994.

Pomona College’s new vice president for student affairs and dean of students, Avis E. Hinkson, brings more than three decades of higher education experience in areas ranging from residential life to student recruitment to undergraduate advising. Her new role, which she began on Aug. 1, marks her return to Pomona College, where she was an associate dean of admissions from 1990 to 1994.

Grow up in a baseball-centric family in the Lakeview neighborhood of Chicago—near the Chicago Cubs’ famed ballpark, Wrigley Field—and start playing tee-ball at 3. Discover that you’re “a little above average” as a toddler-athlete, meaning that you can run all the way to first base without falling down.

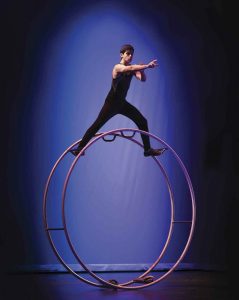

Grow up in a baseball-centric family in the Lakeview neighborhood of Chicago—near the Chicago Cubs’ famed ballpark, Wrigley Field—and start playing tee-ball at 3. Discover that you’re “a little above average” as a toddler-athlete, meaning that you can run all the way to first base without falling down. In kindergarten, attend a hands-on workshop by the nonprofit social-circus group CircEsteem. After failing miserably at juggling scarves, test your sense of balance on a rolling globe—a hard sphere about four feet in diameter—and do so well that the group invites you to join them for practices.

In kindergarten, attend a hands-on workshop by the nonprofit social-circus group CircEsteem. After failing miserably at juggling scarves, test your sense of balance on a rolling globe—a hard sphere about four feet in diameter—and do so well that the group invites you to join them for practices. Partly because the workshop was so cool and partly to escape the soccer practice you despise, join CircEsteem’s new after-school program and discover an awe-inspiring new world—a cavernous circus ring where kids up to high-school age are performing all sorts of acrobatics on the ground and in the air.

Partly because the workshop was so cool and partly to escape the soccer practice you despise, join CircEsteem’s new after-school program and discover an awe-inspiring new world—a cavernous circus ring where kids up to high-school age are performing all sorts of acrobatics on the ground and in the air. At first, stay in your comfort zone with your rolling globe. Then slowly branch out to other circus arts, such as trampoline and partner acrobatics. Avoid two things like the plague: juggling and aerial acrobatics. Conquer your dread of juggling at the age of 8, and two years later, overcome your fear of heights on the static trapeze.

At first, stay in your comfort zone with your rolling globe. Then slowly branch out to other circus arts, such as trampoline and partner acrobatics. Avoid two things like the plague: juggling and aerial acrobatics. Conquer your dread of juggling at the age of 8, and two years later, overcome your fear of heights on the static trapeze. See your first Cirque de Soleil—Corteo—at age 12 and realize that the circus can be truly artistic. Then, when world gym wheel champion Wolfgang Bientzle comes to Chicago to create a Team U.S.A. in the sport, catch his eye and fall in love with the gym wheel under his expert tutelage.

See your first Cirque de Soleil—Corteo—at age 12 and realize that the circus can be truly artistic. Then, when world gym wheel champion Wolfgang Bientzle comes to Chicago to create a Team U.S.A. in the sport, catch his eye and fall in love with the gym wheel under his expert tutelage. Win your first national championship in gym wheel at 14 after telling your mom she didn’t need to stay because the competition was “no big deal.” Go to your first World Championships in Arnsberg, Germany, and make friends from around the world while reaching the finals in all three 18-and-under events, including one fourth-place finish.

Win your first national championship in gym wheel at 14 after telling your mom she didn’t need to stay because the competition was “no big deal.” Go to your first World Championships in Arnsberg, Germany, and make friends from around the world while reaching the finals in all three 18-and-under events, including one fourth-place finish. Two years later, apply to Cirque du Soleil to spend a week at their training facility in Montreal, Canada, and get invited to serve as a temporary gym wheel coach for the Cirque du Soleil acrobats. Then, when the World Championships come to Chicago, defend your home turf by winning two bronze medals.

Two years later, apply to Cirque du Soleil to spend a week at their training facility in Montreal, Canada, and get invited to serve as a temporary gym wheel coach for the Cirque du Soleil acrobats. Then, when the World Championships come to Chicago, defend your home turf by winning two bronze medals. While applying for college, also apply to the École de Cirque in Quebec, a feeder school for Cirque du Soleil. Since you know its three-year program is impossibly exclusive, apply for a gap year in its slightly more accessible one-year program. Get accepted to the three-year program instead. Have to choose between a circus life and Pomona. Choose Pomona.

While applying for college, also apply to the École de Cirque in Quebec, a feeder school for Cirque du Soleil. Since you know its three-year program is impossibly exclusive, apply for a gap year in its slightly more accessible one-year program. Get accepted to the three-year program instead. Have to choose between a circus life and Pomona. Choose Pomona. Even before arriving on campus, make arrangements to form a club at The Claremont Colleges because you want to build a community of people with an interest in the circus arts. Name the club 5Circus and serve as its president for three years before, in the name of continuity, letting someone else take over during your senior year.

Even before arriving on campus, make arrangements to form a club at The Claremont Colleges because you want to build a community of people with an interest in the circus arts. Name the club 5Circus and serve as its president for three years before, in the name of continuity, letting someone else take over during your senior year. Major in neuroscience and decide to become a doctor. But since you didn’t take a gap year before college, decide to take one before entering medical school. Win a Fulbright Fellowship to spend the year in Israel, melding your passions for medicine and the circus by studying an innovative paramedical practice known as “medical clowning.”

Major in neuroscience and decide to become a doctor. But since you didn’t take a gap year before college, decide to take one before entering medical school. Win a Fulbright Fellowship to spend the year in Israel, melding your passions for medicine and the circus by studying an innovative paramedical practice known as “medical clowning.”

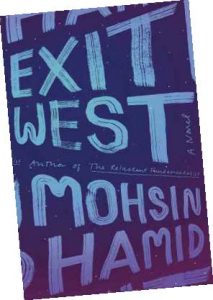

This fall, join the Class of 2022 as they start their Pomona journeys by reading Exit West, a book The Los Angeles Times called “…a breathtaking novel by one of the world’s most fascinating young writers.” Named a Top 10 Book of 2017 by The New York Times, Mohsin Hamid’s work follows two lovers displaced by civil unrest in their home country.

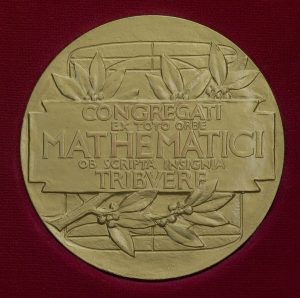

This fall, join the Class of 2022 as they start their Pomona journeys by reading Exit West, a book The Los Angeles Times called “…a breathtaking novel by one of the world’s most fascinating young writers.” Named a Top 10 Book of 2017 by The New York Times, Mohsin Hamid’s work follows two lovers displaced by civil unrest in their home country. Hidden figures no more. That’s the future that Professor of Mathematics Ami Radunskaya hopes to see soon in the world of mathematics: more women—particularly more women of color—in the field.

Hidden figures no more. That’s the future that Professor of Mathematics Ami Radunskaya hopes to see soon in the world of mathematics: more women—particularly more women of color—in the field.

As a thought experiment, we asked alumni, faculty and staff experts in a wide range of fields to go out on a limb and make some bold predictions about the years to come. Here’s what we learned…

As a thought experiment, we asked alumni, faculty and staff experts in a wide range of fields to go out on a limb and make some bold predictions about the years to come. Here’s what we learned… A solar-powered Coachella? That’s a future that alternative rocker Skylar Funk ’10 hopes to see one day. Although there isn’t a solar generator that is big enough to power the Coachella main stage yet—things are moving in that direction, says Funk.

A solar-powered Coachella? That’s a future that alternative rocker Skylar Funk ’10 hopes to see one day. Although there isn’t a solar generator that is big enough to power the Coachella main stage yet—things are moving in that direction, says Funk.