Steven Gutkin ’86 in Goa

IMAGINE FOR A moment that this is your life. Interviewing the likes of Fidel Castro, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Lee Kuan Yew, Jimmy Carter and Shimon Peres. Getting shot at, shelled, detained or banned in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Cuba. Bearing witness to global events such as the rise and fall of the Medellín and Cali cocaine cartels, the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza, upheavals in Venezuela and Indonesia, a coup in Fiji and the defeat of the Taliban.

And now imagine that, as a reward for your efforts, you are “promoted” to a management position, where conference calls, performance reviews and bureaucratic jockeying have taken the place of covering palaces, presidents and the outbreak of war and peace.

What do you do then? Why, you quit your job and move to India with your wife and two sons to start your own weekly newspaper, of course.

At least that’s what you do if you’re former Associated Press (AP) bureau chief Steven Gutkin ’86.

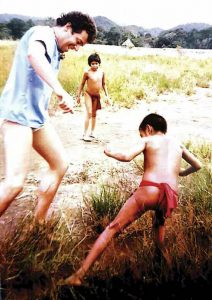

Gutkin playing with Yanomami children in the Amazon jungle

Whether fleeing Colombia because of death threats from the Cali cartel, or ducking and covering during a Taliban shell attack on a battlefield north of Kabul, or witnessing the independence celebrations of the long-suffering people of East Timor, Gutkin has always equated work with adventure and the pursuit of truth. And when he talks about his long career as a foreign correspondent, his war stories unfurl like a tightly wrapped, multicolored Sikh turban.

For instance, early in his career, he and another journalist were left stranded in the Amazon jungle with Yanomami tribespeople by a pilot who took off from a grassy field promising to return in a few hours but came back instead 10 days later. Gutkin and the other reporter were forced to trade their clothes with the tribesmen in exchange for plantains to eat, and he recalls watching dozens of Yanomami click their tongues—their word for “wow”—upon seeing their first magazine.

At the time he was angry about the pilot’s antics, but looking back, he says, “I was afforded a great privilege to spend time deep in the Amazon jungle with an intact hunter-gatherer society completely untouched by Western influence. I don’t think it would be possible to find such people today.”

And then there’s the story he tells about the day Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar was killed. Gutkin had submitted questions to the drug lord’s son, Juan Pablo Escobar, and asked him to get answers from his dad over the phone. While the two lingered on the phone, the police traced their call. Gutkin says, “Father and son spoke about a number of things that day, but among them was going through the answers to a journalist’s questions—that would be me.”

Gutkin soon arrived at the Medellín home where Escobar had been gunned down with a pistol in each hand. He saw blood, shattered glass and Escobar’s half-eaten hot dog. He recalls, “I used the same phone that Escobar had used when his call was traced, partly because he was answering my questions, to call in my reports to the AP.”

AFTER EARNING HIS master’s degree from the Columbia University School of Journalism, Gutkin moved to Venezuela in 1987 and got his first byline in Time magazine during 1989’s violent price riots in Caracas. “You could say this was my first major break in journalism,” he says, “because the Time magazine correspondent was out of station when the riots broke out, and the magazine hired me to cover them instead.”

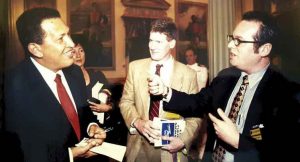

Gutkin interviewing Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez

He then began his long relationship with the Associated Press, covering a coup attempt in 1992 by a young Venezuelan army officer named Hugo Chavez and reporting on the drug wars of Colombia. (He hasn’t seen the Netflix series Narcos but says he did “live it.”) He then became an editor on AP’s international desk in New York.

In 1997 at the unusually tender age of 32, Gutkin returned to Caracas as the AP’s bureau chief in Venezuela, where he covered Chavez’s rise to the presidency and came to know the late leader well, along with the policies that he says led to Venezuela’s implosion. “I’m absolutely sick about what is happening in Venezuela today,” he adds. “One of the most delightful countries on the planet has been driven into the ground by stupid ideology-driven policy. People are going hungry, and misery abounds.”

After the AP set up its first bureau in Havana since the Cuban revolution, he covered the story of Elián González, the 6-year-old boy who was the subject of an international custody battle in 2000 after surviving a boat wreck at sea that killed his mother and her boyfriend. Gutkin spent a week in the mother’s hometown of Cárdenas and wrote a story revealing how the Cuban authorities had lied about her motivations for leaving the island. The AP brass got wind of the piece and, fearing closure of the newly opened Havana bureau, ordered a rewrite. By then it was too late, however, as the original story had already run on the AP’s Spanish wire. In the ensuing fallout, the bureau was allowed to remain in Cuba, but Gutkin was not.

“In some ways, I have always considered being banned from Cuba as something of a badge of honor, but the truth is I love the country and very much would like to return there. I hope enough time has passed now that I will be able to do so.”

In the years that followed, Gutkin always seemed to find himself where the action was.

Gutkin in Kabul after the fall of the Taliban

He was appointed AP’s chief of Southeast Asia services in Singapore and then Jakarta. He became the AP’s first print journalist to enter Afghanistan after 9/11 and rode into Kabul with a triumphant Northern Alliance. He helped lead AP’s coverage of the Iraq War and covered the kidnapping and killing of fellow journalist Daniel Pearl in Pakistan (Gutkin, like Pearl, is Jewish, and they had both been seeking to interview the militants who subsequently killed Pearl after forcing him to say, “I am Jewish”).

As bureau chief in Jerusalem from 2004 to 2010, he led one of the AP’s largest international operations and directed coverage of wars in Lebanon and Gaza and the death of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.

Then a big story broke on the other side of the world that would change his life forever.

In the spring of 2010, a blowout at the Deepwater Horizon platform sent some 210 million gallons of oil gushing into the Gulf of Mexico over a period of five months, making it the largest spill in the history of the petroleum industry.

At the time, Gutkin had been hoping to take up a new position in Mexico City, but the AP convinced him to move to Atlanta to lead the AP’s multitiered coverage of the spill, involving scores of reporters, photographers, videographers, graphic artists and others.

Eventually, however, the story died down, and Gutkin found himself living in Atlanta with no permanent assignment. “The kids were settled in school,” he says, “and we were hoping to buy a home and stay there for a while.”

So, after decades of pursuing big stories and dodging bullets, he accepted a job as deputy regional editor for the U.S. South—“a good gig,” he says, but still “a far cry from the life I had come to love.”

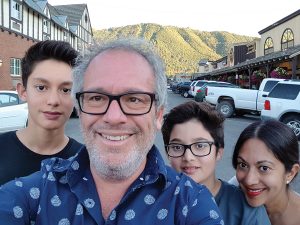

So at the age of 47, with the support of his wife, Marisha Dutt, he decided to leave his AP career behind and start over.

Gutkin with his wife, Marisha Dutt, on their wedding day in India

“I HAD ALWAYS thought about the possibility of doing something on my own, and in the back of my mind I told myself that I’d stay with the AP as long as I loved it, and would leave as soon as I didn’t,” Gutkin explains. “That happened in 2011, when I decided to start a new chapter completely.”

The couple had been traveling to Dutt’s native country of India every year since their marriage in 2002, and in 2008, they had purchased a home in the tiny western state of Goa. “If the idea was to start something on our own,” he says, “Goa seemed the place to do it.”

The first edition of their new weekly newspaper, called Goa Streets, was published on Nov. 8, 2012.

“We started out with a bang, to say the least,” Gutkin says. “Our Goa Streets Flash Mob, days before our launch, attracted about 160,000 views on YouTube, and we arranged hop-on, hop-off party buses around the state, with traditional Goan brass bands aboard, to ferry people to hot spots” around Goa.

For the next four years, Gutkin and his wife, along with a devoted staff, published a weekly newspaper, informing readers about things to see, do and eat in Goa while providing cutting-edge articles on a wide range of topics, including politics, art, literature, the environment and finance.

“Our idea was to bring the idea of an ‘alt-weekly’ to India,” Gutkin says. “We worked very hard and had a wonderful time.”

Looking back, Gutkin says the price for achieving profitability at Goa Streets was too high, however. He gives the example of Goan casinos, whose advertising was essential for financial survival but who would not countenance negative coverage despite a scandalous presence in the state.

“I do not want to choose between my principles and my pocketbook,” he says of his eye-opening introduction to media entrepreneurship in India.

About a year ago, the couple decided to quit printing their weekly and publish online only. Currently, they are in the process of turning Goa Streets into a probono publication that promotes art, culture and responsible citizenship in the state and beyond—with any hopes for further monetization postponed to a later date.

“We have a great brand,” says Gutkin. “Goa Streets will live on.”

At the same time, they have ventured into a brand new arena—constructing sustainable luxury villas in Goa, an enterprise that has opened what Gutkin calls “a completely novel and entirely welcome new path in life.”

A selfie with Gutkin, his two sons and his wife Marisha Dutt

Their main project at the moment is a villa in the serene village of Sangolda. It is designed by award-winning architect Alan Abraham, who built one of the most famous homes in India—a seaside penthouse in Mumbai for his brother, Bollywood actor John Abraham, called Villa in the Sky. The new villa is nestled beside a flowing stream on a property filled with coconut palms.

“When Alan came to check out the property and saw the towering coconut trees, the first thing he said was, ‘We’re keeping them,’” Gutkin remembers. “So instead of cutting the trees to build the house, we built the house around the trees. We’re calling it Villa in the Palms, kind of like the sequel to Villa in the Sky.”

It’s a long way from his old globe-trotting life on the cutting edge of the news, but Gutkin says he has no regrets. And he promises he’s not done with journalism yet.

“My next big goal in life is to write more for Indian and international publications,” he says. “I’ve lived in a lot of places, seen a lot of things, and feel I have much to say.”