Crossing the border can be a cruel social leveler. For José Clemente Orozco, as for many Mexican immigrants, entering the United States proved a harsh and humiliating experience. But unlike most of his compatriots, the renowned muralist endured immigrant indignities at opposite ends of the map, on both the southern and northern edges of the U.S.

Orozco’s first and most famous frontier passage came in 1917, more than a decade before creating his heroic Prometheus at Pomona College. U.S. customs agents at Laredo, Texas, confiscated and destroyed most of the paintings he was carrying, claiming that they were somehow obscene. It was a bitter first impression of the country he had looked to for new artistic horizons. Instead, he found at first a vexing sort of censorship that would worry him for many years to come.

Orozco’s first and most famous frontier passage came in 1917, more than a decade before creating his heroic Prometheus at Pomona College. U.S. customs agents at Laredo, Texas, confiscated and destroyed most of the paintings he was carrying, claiming that they were somehow obscene. It was a bitter first impression of the country he had looked to for new artistic horizons. Instead, he found at first a vexing sort of censorship that would worry him for many years to come.

The second border incident is less notorious in art circles, though Orozco himself mentions it in his autobiography. This time, the brush with authorities didn’t involve his art. But it left a personal wound that might feel familiar to many fellow immigrants, regardless of profession, fame or social class.oro

During that same trip, Orozco made a tourist stop at Niagara Falls. At one point, he crossed into Canada to get a better view of the binational natural wonder. World War I was raging and authorities feared an assassination attempt on England’s Prince of Wales, who happened to be visiting at the same time. Adding to a climate of international tension, Orozco recalls, newspapers blared “in enormous red headlines” an account by a “yellow journalist” about Pancho Villa’s revolutionaries assaulting a train in Sonora and allegedly violating all the women on board.

“I had been there a couple of hours when a policeman detected something suspicious in my countenance and asked for my passport,” Orozco writes of his aborted Canadian sojourn. “On seeing that I was a Mexican he literally gave a jump and expelled me on the spot, himself conducting me back to the American side. ‘Mexican’ and ‘bandit’ were synonymous.”

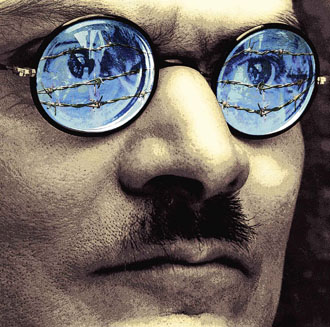

In either incident, those border agents could not have imagined that they were deporting—or destroying the work of—an artist who was to become, in the words of Art Professor Victor Sorell, “the Michelangelo of the 20th Century.” Although somewhat overshadowed by the other two members of the esteemed troika of Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, Orozco has gained increasing attention and respectability in the United States, especially in the past decade. He was the subject of a 2007 PBS documentary, Orozco: Man of Fire, and of a 2002 traveling exhibition, José Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934, organized by the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, site of the last of three murals the artist created during that seven-year stay in this country.

In written essays and interviews, experts paint a portrait of an artist whose life and labor were deeply and permanently influenced by his binational lifestyle. Of Mexico’s big three muralists— Los Tres Grandes—Orozco was the one who spent the most time in the United States, a total of 10 years during four separate stays—in 1917-19, 1927-34, 1940 and 1945-46. His visits coincided with the most convulsive global events of the 20th century, including both world wars. Orozco was living in New York the day the stock market crashed in 1929, becoming an artistic eyewitness who documented its aftermath in grim urban tableaus during the first years of the Great Depression. One of those paintings, 1931’s Los Muertos, depicts skyscrapers collapsing in a jagged jumble, an image that would be used 70 years later by a Mexican magazine to illustrate the tragedy of 9/11.

Seen through the prism of his immigrant experience, Orozco’s story will feel familiar even to those far from the rarefied art circles he inhabited. The Niagara Falls fiasco raises issues of xenophobia and racial profiling that still resonate to this day, almost 100 years later. Beyond that, all immigrants can relate to elements of the artist’s cross-border existence—the struggle to navigate the culture gap, to carve out a space where they’re not always welcome, to build a new life from scratch, to move forward despite crippling setbacks. In Orozco’s case, that included periods of poverty and isolation, epic failures as an artist and early public scorn for his work. Not to mention the loss of one hand in a fireworks accident as a young man, a disability that would have sidelined most aspiring muralists, since it is such a physically challenging art form.

“He certainly represents that [immigrant] spirit of gumption and upward battle,” says Laurie Coyle, who wrote, directed and produced the vivid Orozco documentary along with collaborator Rick Tejada-Flores.

The incident in Laredo came as a culture shock for Orozco. Though no records of the destroyed paintings exist, experts believe they were part of a series of watercolors called House of Tears, depicting brothel scenes. They were studies in the human psyche, not sexuality. They may have been grim and hopeless, but not titillating. “The pictures were far from immoral,” writes Orozco in his autobiography. “There was nothing shameless about them. There weren’t even any nudes.”

His reaction: Just keep moving. “At first, I was too dumbfounded to utter a word, but then when I did protest furiously, it was of no avail,” he writes, “and I sadly continued on my way to San Francisco.”

Though barely mentioned again, the border incident created a sort of philosophical angst for the artist, with long-term effects, according to Renato González Mello, professor of contemporary art at the National University of Mexico (UNAM) and the foremost expert on Orozco. The encounter represents a historic clash that flares when Latin Catholic culture meets Anglo-Saxon Protestantism, he explains. Aesthetically speaking, that clash hinges on traditional distinctions between high and low art, a dichotomy that was of particular concern to Orozco and other Mexican artists of the revolutionary era who brashly worked to breach it.

“The incident makes him see that the distinction between high and low is subject to legal definitions,” González says in a bilingual phone interview from Mexico City. “What in Mexico would be a problem of good taste or bad taste, or simply a problem of class, in the United States becomes a matter of law enforcement… This is like a completely different planet for Orozco, and he sees it as incredibly strange and irrational.”

Getting used to new rules would take time. For the two years he spent in the United States on that first visit, Orozco did not produce any art works of note. Instead, he painted movie posters and Kewpie dolls for subsistence. “I still believed that there was some law against art in the United States,” the artist is quoted saying in the documentary, “and I wasn’t taking any more chances.”

Orozco returned to Mexico in 1919, on the cusp of the country’s public mural movement. But Orozco’s first major commission in 1924 was soon plunged into chaos when angry conservative students defaced his murals at the capital’s National Preparatory School, because they considered them seditious and sacrilegious. Orozco recalls that he and Siqueiros were both “thrown out into the streets like mad dogs.”

Orozco (front row, fifth from right) with an unidentified group in Frary Hall, where he would paint his Prometheus. Photo courtesy of Honnold-Mudd Library.

The muralists managed to finish the work two years later, to great acclaim. But soon, government support for the mural movement dried up, and with it the hope for new commissions. With that discouraging backdrop, noting that “there was little to hold me in Mexico,” Orozco decided to set out once again for El Norte, arriving in New York in the winter of 1927.

“It was December and very cold,” he writes. “I knew nobody and proposed to begin all over.”

For six months, Orozco lived in virtual anonymity, until hemet American journalist Alma Reed, who was to become his agent and chief cheerleader. She had been referred to the artist by another writer, Anita Brenner, daughter of Jewish emigrants to Mexico who was familiar with his work and expressed concern for his “sad and lonely and neglected” condition. But she warned Reed that Orozco could be difficult, a man “tortured by hypersensitive nerves” who was “easily hurt.”

In her own book about Orozco, Reed recounts going to meet the artist for the first time at his basement apartment in Manhattan. Instead of a temperamental grouch, Reed found “a gentle host” with a “cordial smile” and a “vague touch of the debonair.” She was incensed by the way her fellow Americans were ignoring him, a snub she called “a breach of international courtesy.”

“Not one of our very wealthy and socially prominent art patrons or subsidized cultural institutions had made the slightest gesture of welcome to this renowned master of the long-lost technique of true fresco …,” writes Reed. Impelled by a “nebulous desire to make amends,” she vowed to “let him know that one ‘Norteamericana’ felt honored to welcome him, though somewhat belatedly, to Babylon-on-Hudson and had come to wish him all the success and happiness he so richly deserved.”

In the next few years, Reed did much to make that success happen. She would be instrumental, in fact, in helping the painter land his three mural jobs, at Pomona and Dartmouth colleges and in New York at the New School for Social Research. And she helped introduce Orozco to a diverse and stimulating set of new contacts through the Delphic Circle, an intellectual and literary salon founded by Greek poet Angelos Sikelianos around a vision of universal brotherhood. The group, which had staged the ancient Greek tragedy Prometheus Bound in Delphi the same year Orozco arrived in New York, would be extremely influential in his work.

“I think the adoration that Alma Reed demonstrated toward him, the attention he received in New York at the ashram of the Delphic Circle, that kind of deified him in the same way that Rivera had been deified,” says Sorell, university distinguished professor emeritus at Chicago State University. “His confidence must have grown exponentially.”

Orozco spent more than two years in New York before landing his first mural commission at Pomona. Meanwhile, he survived partly by catering—or caving—to the trendy demand for Mexican art that developed in the United States and Europe during the 1920s and 30s. He made paintings of what writer and curator Diane Miliotes describes as “landscapes that verge on the folkloric … with these stock images of a pueblo, or an indigenous woman and her child, and maybe a maguey plant or two.”

In an essay for the companion book to the Dartmouth exhibition, Timothy Rub notes that “Orozco developed a keen if somewhat cynical awareness of what American patrons expected of Mexican painters.” In the same book, González Mello puts it more bluntly: “The first thing Orozco does upon his arrival (in New York) is become a professional Mexican.”

Personally, the artist found the whole thing distasteful. Even in Mexico, he was harshly critical of revolutionary artists who pandered to the folkloric, glorified the indigenous or idealized the concept of nationality, or Mexicanidad, all of which had been the bread and butter of the mural movement.

In the United States, he had to deal with the market on its own terms, at least to some extent.

“He’s dealing with an audience that doesn’t know anything about Mexico, except that it’s exotic and exciting and violent,” says Miliotes, who served as in-house curator for the Hood Museum exhibition. “And there’s this wonderful vogue for it that he’s trying to take advantage of, but it forces him to try to navigate that craze without feeling that he’s totally selling himself out.”

Those concerns would soon fade. In 1930, Orozco put himself firmly on the map as a world-class artist with his own daring identity when he painted Prometheus, the first fresco by a Mexican artist in the United States. The commission for the space above the fireplace in Frary Hall was pushed along by Catalan art historian José Pijoán, who was then teaching at Pomona.

At first, he considered calling on Orozco’s rival, Diego Rivera. But it was Pijoán’s colleague, artist Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna, who steered the project to Orozco. Crespo de la Serna, then teaching at Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, was a friend of Orozco and would become his assistant on Prometheus. “… The beauty of it is that a few kids and a few penniless professors had the faith and the courage to institute the proceedings and went ahead without committees, boards, or rubber stamps,” Pijoan wrote in the Los Angeles Times shortly after the work was completed.

The landmark work would become “the first major modern fresco in this country and thus epochal in the history of the medium,” according to the late art historian David W. Scott, former chair of the Art Department at Scripps College.

Yet, as bold as the fresco was, Orozco at first avoided painting a penis on Prometheus, the heroic nude that towers over diners at Frary. While more lofty artistic considerations about classic representations of the male physique may also have been at play, the artist was certainly well aware of his local critics and the risk of offending puritanical community standards. “Absolutely, I think he was hesitant (to add the penis) because there was disapproval that he was painting a very large naked male figure on the wall,” says Coyle, the documentarian. “He was reading the press and some of these critical articles were actually appearing while he was working on the mural.”

Yet, as bold as the fresco was, Orozco at first avoided painting a penis on Prometheus, the heroic nude that towers over diners at Frary. While more lofty artistic considerations about classic representations of the male physique may also have been at play, the artist was certainly well aware of his local critics and the risk of offending puritanical community standards. “Absolutely, I think he was hesitant (to add the penis) because there was disapproval that he was painting a very large naked male figure on the wall,” says Coyle, the documentarian. “He was reading the press and some of these critical articles were actually appearing while he was working on the mural.”

Orozco didn’t have to check the newspapers to find condemnation. He embarked on the project, he writes, “to the disgust of the trustees who would grumble as they made their way through the refectory and eye the scaffoldings askance, disposed to fall upon me at the first mis-step.”

A penis was appended later to the fresco when Orozco returned for a visit months later, but it didn’t adhere properly because the wall had dried. Since then, of course, the missing member has been the subject of student jokes and pranks. The genital shortcomings didn’t deter artist Jackson Pollock, an Orozco admirer, from famously declaring Prometheus “the greatest painting in North America.”

Despite the controversy, the Pomona campus community, especially faculty and students, defended the artist’s right to express himself. The following year, in the face of yet another public outcry, administrators of the New School defended his depiction of Lenin and Stalin in his series of five frescoes with sociopolitical themes. The support in both cases must have been reassuring since he had seen how vicious public censorship could be, on both sides of the border. Later, the Dartmouth community also would stand up for his artistic freedom at a time when murals by Rivera in New York and Siqueiros in Los Angeles were being whitewashed or destroyed for political reasons.

Orozco returned to Mexico in triumph in 1934 and proceeded to create astonishing works of art that mark the pinnacle of his career. He completed his masterwork at Guadalajara’s Hospicio Cabañas, crowned by the soaring image of The Man of Fire in the cupola of the colonial structure, dubbed the Sistine Chapel of the Americas. In 1940, hailed as a celebrity, he returned to New York and created the anti-war mural, Dive Bomber and Tank, commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art. Orozco wrote his final chapter in the United States in 1945-46, near the end of his life. This time, the trip was primarily personal. He came to this country for the last time out of love. And he left with a broken heart.

Earlier, the aging artist had fallen head over heels for the young and beautiful lead dancer for the Mexico City Ballet, Gloria Campobello. But when his mistress gave him an ultimatum and his wife Margarita refused to give him a divorce, the stage was set for a midlife crisis that ripped open the man’s hermetic heart.

Orozco left his family and moved to New York to be with Campobello. But she soon abandoned him and returned to Mexico, ignoring his pathetic, pining letters. The artist found himself alone in Manhattan once again, just as he had started. Now all he wanted was to go back home and he begged his wife to take him back: “I know that I have behaved very badly with you and I have paid dearly with my remorse,” he wrote. “I don’t want to live here anymore. I don’t want any of it. Or even to see it again. My only thought is to return to you if you will take me back.”

And she did. He returned to Mexico City, with only three more years to live. His final works evinced a premonition of death. When it finally came, on Sept. 7, 1949, it caught him in the midst of a new project, painting a public housing mural.

Orozco had come to this country as an unknown, and left as an artist of global stature. Far from leveling him, immigration had vaulted him to new heights.

“I really think his experience in the United States inspired him to speak to people across borders,” says Coyle, the documentary filmmaker. “He did not want to be seen as a national artist or a Mexican artist. He really kind of chafed at those boundaries and divisions that people used to define themselves and what they were doing.”