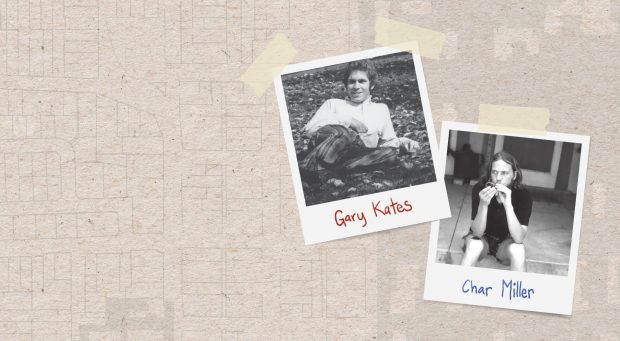

Almost 50 years after they met as students at Pitzer and shared a house on Indian Hill Boulevard, Pomona College professors Gary Kates and Char Miller revel in a friendship that remained tight as they crisscrossed the country for graduate school and teaching jobs. They reunited in the 1980s as professors at Trinity University in Texas before Kates left for Pomona in 2001. In 2007, Miller followed. Back together in Claremont, they have offices two doors down from each other in Mason Hall. As Miller wrote in dedicating a book to Kates, his wife and their two children, their families’ bonds have become as thickly intertwined as the gnarled live oaks arching over the streets where they have lived. Kates and Miller recently sat down to reminisce with PCM in a conversation that has been edited for length and clarity.

Gary Kates: I think we remember when we met, but we may remember the remembering more than anything, because it was so long ago. It was in Huntley Bookstore of The Claremont Colleges, probably around the history books, and we stood a long time talking to each other.

Char Miller: Judi, now my wife of 45 years, introduced us. Gary had been her RA. I’ve said this to Gary before: It was like I met my brother, which I don’t have, but he has become that.

GK: It was September of 1973. Char and Judi were living in a home in South Claremont. Lynne, now my wife of 44 years, and I were living at 545 Indian Hill with John Moskowitz, who remains a close friend. John felt a little like a third wheel living with a couple, which was understandable, so midyear he moved out.

CM: And Judi and I moved in. The house was really funky, and that might also have driven John crazy. It’s been heavily fixed up since then. It was old Claremont; there was no insulation in the house and any wind went right through its very thin walls. But it was cheap, and it was close to the colleges.

GK: Char was much more hippie-looking then.

CM: Much more hair.

GK: Char’s hair flowed down to his shoulders and at times needed a band be pulled back. My hair looked longer than it was because it was kind of curly and kinky in those days, but never as classical ’60s as Char.

CM: I was going for the classical ’60s. To come to California, like for many at that time, was a chance to remake yourself. It did work in the sense that it gave me a life that I couldn’t have imagined before I got here and a chance to meet people that I wouldn’t have met had I not arrived—especially Judi!

I had dropped out of NYU and worked for a while but after about six weeks, I thought, this working stuff is hard, so the next fall I transferred to Pitzer. On my way to Claremont my car broke down in Bridgeport, California, in the Eastern Sierra. I had to hitchhike to Pitzer and got a ride from a guy in an 18-wheeler who took me all the way down Highway 395 through the Cajon Pass and dropped me off at Exit 47.

Another thing about Claremont in those days, the air quality was such that there were many days when you did not go outdoors. There was what we used to call the “smell of the ick” from the Kaiser Steel Mill in Fontana, and then all the cars. The air quality was so horrific that riding a bicycle from 545 Indian Hill to Pitzer College, you felt like you’d been running a marathon. There were days when I was just like, I’m not going to school. This is crazy. And obviously we didn’t have Zoom.

GK: It was so smoggy that there were maybe 100 days out of the year that you couldn’t see the mountains from Claremont. Maybe today there are five or 10 of those days.

CM: But you know, what was so much fun in that house was that it was very communal, not just between the four of us, but also lots of friends. Gary was teaching religious school at Temple Beth Israel, where we all belong still, and he would bring his students over. There would be songs and singing and Gary would be playing guitar.

GK: We listened to a lot of Phil Ochs in those days, who is not well known today but was a Dylan-esque protest singer who tragically committed suicide in 1976. But 1972 to 1974 was his heyday, and we listened to a lot of other folk music like that. Peter, Paul and Mary certainly. That was also your first year of baking bread, Char.

CM: Every Friday night we would bake challah and we got really good at it. I still get comments from people who had dinner in our house in ’73 and they say, “I remember that bread.”

GK: The housing stock in Claremont was much less upscale than it is today. Today, I think it would be hard for any student to rent out a full house in Claremont. They might be able to get a back home or a garage apartment. In the early ’70s, it didn’t feel unusual at all for college seniors to rent a home.

CM: A ceramist at Pitzer, Dennis Parks, owned the house, and a series of our friends had gone to work in his studio up in Nevada. One day, he turned to one of them and said, “Who is this Judi Lipsett? She keeps sending me checks.” He didn’t realize we were paying him something like 300 bucks a month, a cost that was cheaper than the dorm.

GK: It was a four-bedroom house, but we had changed two of the bedrooms into studies. For the studies, I was with Judi, and Char was with Lynne.

CM: It was also a kind of professionalized thing, that we were committed to doing this pretty early on. Part of what was so great was I had this incredible friend who was an historian who in that semester was finishing his senior thesis—on his electric typewriter. But it was so much fun to watch Gary go through this process, because I was going to try to replicate it the next year. Gary’s been my guide in a lot of things, but it started that spring.

GK: I don’t think it occurred to us until years later that it was actually very rare at that time for a Pitzer undergraduate to go to history graduate school. Pitzer [founded in 1963] wasn’t very old at that time.

CM: The faculty of Pitzer were fantastic and really helped me understand why I should do what I wanted to do. It was kind of a heady time.

GK: All the colleges were smaller, and certainly Pitzer being so new was under-resourced and more dependent on the other colleges. Both of us had mentors at other colleges too. Today each of the colleges is better, a little bigger and stronger than they were then.

CM: Every one of them is so strong now. I feel so lucky being back here.

The other thing we did at 545 was we had a garden in the backyard, which was problematic, I now think in retrospect. The professor had a kiln back there, and there was all sorts of debris and I suspect toxicity in the soil, which might have explained why things didn’t grow very well. But it was part of the back-to-the-land movement. Trying to grow your own food was consistent with trying to make your own bread. We’d have these big sumptuous meals that spread across the table with 10 to 12 people sitting in totally mismatched chairs.

GK: The thing I remember about that era that I think is still true with college students today, and I hope it is, I’m sure it is, is that we constantly talked about our classes and what we were reading and learning. And there’s a way in which five years later, I wasn’t sure if I took that class or if Judi took that class and I just listened to it and learned through osmosis because she was talking about it. It all kind of merged and the education you got was as much through one another and their experience of a class being reported daily, as if you actually took it.

CM: That’s what we always say as teachers now, that you learn surely as much outside the classroom as you do inside and that was a beautiful example of that, in part because the readings that we had were just dynamite. Absolutely fantastic and challenging, and because we were living with people who loved to talk about books and still do.

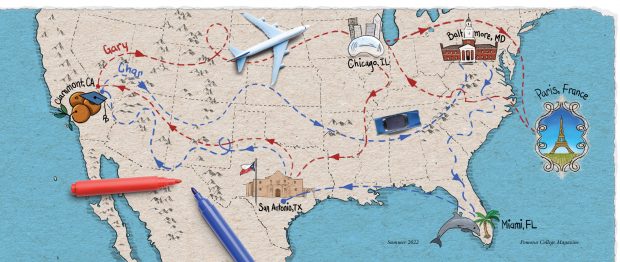

Judi is a writer and editor—she has edited most if not all of Gary’s books. Lynne went to medical school in Chicago and Gary went to graduate school at the University of Chicago. Then I went to Johns Hopkins for graduate work. When we were in Baltimore and they were in Chicago, we deliberately flew through Chicago so that Gary and Lynne could come out to the gate and we could see them, back when you could do such things. I remember we were once standing there and Gary’s looking very nervous and, finally, he said, “That’s Carl Wilson over there,” of the Beach Boys. Gary said, “I’ve got to go talk to him, but I’m not going to.” Judi said, “What can he say? Go over there.” Gary went over and introduced himself, and it was like this moment of great joy, in part because we could watch it happen in real time.

GK: When Judi and Char got married in the spring of 1977, I was in Paris doing research for my dissertation. Lynne went to the wedding and I didn’t. Today people would hop on a plane and make the transatlantic trip, but in those days you didn’t do that. You thought of it as a world away. But Lynne went to their wedding, and when I got back to Chicago where Lynne was in medical school, she announced to me that, well, they got married; we’re getting married. And it really was just like that, and so we got married the next year because they did.

CM: I mean there are worse reasons to get married.

GK: Well, it’s still working.

CM: After Pitzer, we were all in graduate programs in one form or another. We were going across the country, and whether by car or airplane, we were connecting with one another. Then I was teaching in Miami in the fall of 1980 when a position opened up at Trinity University in San Antonio. It was advertised in January right when our son [Ben Miller ’03] was born. And Gary was already in Texas at Trinity. There was a phone call, and he said, “This job is coming; put your hat in the ring.” I was on a visitor position at Miami, learning how to be a teacher, learning how to be a father, learning how to do all these things in temperatures that were very hot and astonishingly humid. It was at the time that the Mariel Boatlift occurred when Castro released lots of people, including many prisoners, and Miami became a shooting gallery. Literally down one block from our house, a drug raid happened with snipers stationed on our roof. I applied.

GK: Char was an unusual candidate in those days, because he had already had his dissertation accepted by a press and about to be published. As a kind of newbie pre-assistant professor, it made his CV stand out and made him a distinctive candidate for a tenure-track position. I think that’s one reason why Trinity wanted him. The other is Char and I were part of a more general effort to move Trinity from a good regional university to what might be called today a national liberal arts college. I think Char caught the wind of those sails, and it all just seemed to work out. It was magical. We couldn’t have made it work out. I was an assistant professor and junior. It took the seniors and the administrators wanting to do that.

CM: And then, like now, we lived half a mile away from each other in San Antonio. In part because Gary and Lynne put the earnest money down on a house and said, “You’re gonna like it.”

That experience of Gary with the guitar and his students and Phil Ochs, we would replicate at Trinity together. When I was teaching my U.S. in the 20th Century class, Gary would come and we’d go outside, sit under a spreading oak tree and we would teach them the songs. The song leader part of him came roaring back out. You’d get these 18-year-old, 19-year-old Texas kids singing antiwar songs. Then we would sit and talk about what they meant and what the motifs were, and why Phil Ochs and others like him were so invaluable as cultural markers. Twenty years later, they had become a way to talk about the Vietnam War and protest politics, a lot of which was born in the house at 545.

GK: This may be idealization and romanticism, but a lot of people sang more then, because we didn’t have these things in our ear. We didn’t have Spotify. We didn’t have anything really; we had radio. But the privatization of music into one’s ear is something recent, and you don’t hear college kids singing as much as you did then, excepting in a cappella groups and other organized singing.

CM: And I had that kazoo, if you call that music.

GK: I’d forgotten that.

CM: That might have been the next year, but 545, as it had been the previous spring with Gary and Lynne, was a hub for a lot of folks who have gone on to have really interesting lives. I feel very lucky to have had that year-and-half in that house. There was a maturation involved in the process. We weren’t living in a dorm. We had to figure out how to get food. Gary would go down to the Alta Dena Dairy and come back with chunks of cheese that no one in their life could finish eating. But it was cheap, like, why wouldn’t you buy it? And leeks when none of us knew what to do with a leek, but we would chop it up and put it in the soup. And those were the ways that you recognized you could probably survive this life.

GK: Char, don’t forget about the 89-cent Algerian wine.

CM: Oh God, yes. Couldn’t get enough of that. But 89 cents in the ’70s it would be a lot more now, more than Two Buck Chuck from Trader Joe’s. It was not any better than Two Buck Chuck.

GK: Two Buck Chuck’s a lot better.

So by the early 1980s, there we are in San Antonio, not living in the same house anymore but we’re living literally two blocks away, and so our families grew up together. We’re the closest of friends, all of us. That’s the way it was for 20 years, and then I came out to Pomona to become dean of the College.

When I got to Pomona, the environmental analysis program was in dire need of more staff, and I went to the founder of the program, Rick Hazlett, and I said, “Look, I don’t want to impose anybody on you, but if you need someone ….” I told him about Char, who by then had migrated from a more conventional U.S. historian to one who specialized in issues of environmental justice and environmental studies more generally. Rick interrupted me and said, “I’ve read things by Char Miller. Are you saying you could get Char Miller here for a year?” With his blessing, we were able to get Char into a visiting position.

Then Char stayed for another year. I always felt funny about it, because on the one hand Char was a great help. I knew he would be: He was then as he is now a dynamic professor, so he was getting his own following of students. But at the same time, I felt very sensitive to issues of whether I was bringing in my friends to take faculty positions that at Pomona College anyone in the country would like to have. I was very set, OK, a two-year visitor. But then, like it or not, Char needs to head back to Trinity.

We had a new president at Pomona, David Oxtoby, and he was trying to understand the needs of environmental analysis. He said, “Well, what about Char Miller?” I basically told him I was worried about nepotism. And David said the strangest thing to me that I will never forget. He said, “Gary, you can’t allow your friendship with Char Miller to get in the way of what is in the best interest of Pomona College.”

At that point, I simply turned the issue over to my associate dean Ken Wolf, and I said, “Look, if there’s a way that you and President Oxtoby want to keep Char Miller, you put this together. I’m backing off.” And that’s how Char became a permanent member of the Pomona faculty.

CM: From my son’s point of view, there’s never been a job that I’ve gotten that Gary wasn’t somehow involved in. Outside of Miami, that’s actually true.

GK: Our kids, Emily and Max, are very good friends with Char’s kids, Ben and Rebecca. They’re about the same age, give or take a year.

CM: My son Ben works in Washington now, and Gary’s son Max works at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, and every summer they spend at least a day together hanging out by the pool with their wives and children. We get these photographs of the next generations interacting in a really cool way. It’s fun that our various grandchildren know each other. And it started in the bookstore, and was nurtured at 545. I was walking by the house this morning. I pass it frequently and those memories pop up all the time.

GK: We live only a few blocks from each other now.

CM: And every time Gary’s out of town, he forgets to stop his L.A. Times, and either Judi or I stroll over to their house, pick it up and hide it.

Some 26,000 students from more than 4,000 colleges auditioned for the chance to be among the 36 competitors in the Jeopardy! National College Championship, televised in February.

Some 26,000 students from more than 4,000 colleges auditioned for the chance to be among the 36 competitors in the Jeopardy! National College Championship, televised in February. PIT

PIT What Is Love?

What Is Love? Don’t Wait, Create: How to be a Content Creator in the New Digital Revolution

Don’t Wait, Create: How to be a Content Creator in the New Digital Revolution Eyewitness to AIDS: On the Frontlines of a Pandemic

Eyewitness to AIDS: On the Frontlines of a Pandemic

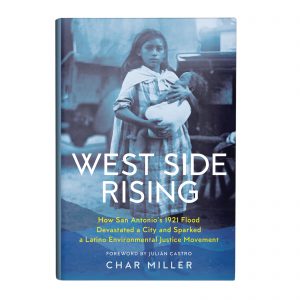

With the coming release of the paperback edition of Environmental Analysis and History Professor Char Miller’s 2021 book, West Side Rising: How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement, PCM’s Sneha Abraham talked with Miller about what happened when the waters receded—and the issues that remain more than a hundred years later. The interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

With the coming release of the paperback edition of Environmental Analysis and History Professor Char Miller’s 2021 book, West Side Rising: How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement, PCM’s Sneha Abraham talked with Miller about what happened when the waters receded—and the issues that remain more than a hundred years later. The interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.