Workers survey the 30-foot sculpture ghandiG by Peter Shelton ’73 at the museum’s former location before moving it by crane across College Avenue to its new home.

Drivers who regularly ventured past the Pomona College campus in the early mornings of October and November 2019 likely witnessed a strange ritual at the intersection of Bonita and College avenues.

Day after day, a procession of student interns crossed the street, slowly rolling stainless-steel restaurant-style carts loaded with slate-gray boxes tied down with brightly colored bungees. Motorists waited as the parade carefully bypassed the myriad yellow warning bumps near the curbs. Reaching the other side, the interns gently maneuvered the carts up to the sidewalk and then onto the ramp of the newly completed Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College.

The museum collection was arriving at its new home. Finally.

For many people, the words “Moving Day” trigger fear and apprehension from beginning to end: the monumental chaos of sorting and packing items, the crucial task of hiring a trustworthy moving team and the suspense mixed with dread of opening boxes at the new location, hoping for minimal damage. But for the staff at the Benton, “Moving Day” was a welcomed phrase for a transition that was long overdue and took nearly two years to complete.

Intern Emily Petro ’21 sorts and labels arrowheads from the Native American Collection.

When news of the 2017 groundbreaking for the spacious new $44 million state-of-the-art museum at the southwest corner of Bonita and College was announced, there was a cheer of relief that all objects in the museum collection would be under one roof at last. For more than 10 years, as many as 13,000 objects in the growing collection had been spread out in three satellite venues: Montgomery Art Gallery, Rembrandt Hall and Bridges Auditorium. The Native American Collection, first assembled around the turn of the 20th century, occupied various locations—among them the basement of the humanities building at Scripps College, then Sumner Hall, and in 2011 the lower level of Bridges.

Celebration quickly dissolved into the electric hum of brainpower as staff began to strategize. Here was a chance to do an up-to-date inventory of every collection item before safely packing and transporting objects as diverse as Andy Warhol Polaroids, Goya etchings, alabaster bas-relief sculptures, large abstract paintings, beaded Sioux leggings and contemporary art by Pomona alumni, including Helen Pashgian ’56 and Chris Burden ’69.

Such an inventory had never been done before.

Workmen prepare to move ghandiG by Peter Shelton

“I had been warned by colleagues that moving a collection is the single most difficult and yet rewarding task a registrar could ever undertake,” says Steve Comba, associate director/registrar at the Benton—who already had twice overseen moves of the Native American Collection.

Objects didn’t have to travel physically far—all satellite locations were blocks or buildings away—but that didn’t make the task less daunting. Handling objects at any step of the process is always a risk, says Comba. “There’s always the possibility of human error. We wanted to do this right. We had to take our time.”

Objects didn’t have to travel physically far—all satellite locations were blocks or buildings away—but that didn’t make the task less daunting. Handling objects at any step of the process is always a risk, says Comba. “There’s always the possibility of human error. We wanted to do this right. We had to take our time.”

Comba brought on board independent collections manager Karen Hudson, who assumed duties as move coordinator/registrar. “Before you move anything, you need to know what you have,” she says about the time-consuming and labor-intensive process of creating the inventory. “You start by opening up every box, in every storage room and in every building. I had my eye on every single object in the collection.”

Comba brought on board independent collections manager Karen Hudson, who assumed duties as move coordinator/registrar. “Before you move anything, you need to know what you have,” she says about the time-consuming and labor-intensive process of creating the inventory. “You start by opening up every box, in every storage room and in every building. I had my eye on every single object in the collection.”

Going through hanging racks, cabinetry and Solander storage boxes one by one for almost a year, Hudson compared each item to its own unique catalog number, cross-checked the database and updated all pertinent information. She noted items with missing numbers, objects that had been numbered incorrectly and other discrepancies.

“You don’t want to move problems,” sums up Hudson. “You solve them first before you pack them up.”

As with any move, surprises were uncovered. For years Comba thought that a rare Sioux ceremonial rattle had been lost; he was thrilled when the beautifully quillworked and beaded treasure was discovered during the inventory. Another surprise: The museum’s collection grew from 11,000 objects pre-inventory to nearly 13,000 in late 2018. (Note: Because of additional gifts to the collection since 2018, that number is now officially 16,000.)

The first museum piece arrived at its new home in spring of 2019.

In the early morning of March 22, spectators watched a 30-foot-tall bronze sculpture dangle from a hoist and crane that was inching its way down College Avenue. No trees or overhead wires blocked the transit. Under a blue sky, there was just a steady progression forward: ghandiG was on the move.

Purchased by the college in 2006, the ethereal sculpture by Pomona alumnus Peter Shelton ’73 was making its way to a new home amid the landscape of the Benton, which was still a work in progress at the time.

Moving ghandiG involved crews severing the sculpture’s support cabling system at the old location, transporting the artwork two blocks and then installing it—with new cabling—at the prominent corner. Shelton was consulted about the proper orientation for his sculpture, which now welcomes visitors to the museum in a striking way.

While ghandiG was officially the first piece of art to be moved to the Benton, it would be months before the rest of the collection joined the sculpture at the new location. Transporting those other items was far less dramatic—but there were still some heart-pounding moments.

The process involved the meticulous packing of hundreds of paintings, pottery works, photos and more. Comba, Hudson and a third member of the museum staff were joined by a team of interns Hudson described as invaluable. “We needed their help, their youthful stamina and enthusiasm,” she says. Comba goes further, calling them “rock stars.” He adds that the collection-moving interns weren’t all art history majors. “We had conservation majors from Scripps College and athletes from Pomona,” he says. “They each brought their own skills to the project.”

The museum could have hired an expensive professional art-moving company for the entire job, but since the Benton is a teaching museum with a robust internship program, the collection move presented an exceptional chance for hands-on, behind-the-scenes, roll-up-your-sleeves learning. Twelve interns—among them Pomona students Nina Mueller ’19, Ethan Dieck ’22, Jem Stern ’22, Quin Fraley ’22, Katherine Purev ’23 and Emily Petro ’21—stepped up for a challenge that lasted from April 2019 to March 2020.

The museum could have hired an expensive professional art-moving company for the entire job, but since the Benton is a teaching museum with a robust internship program, the collection move presented an exceptional chance for hands-on, behind-the-scenes, roll-up-your-sleeves learning. Twelve interns—among them Pomona students Nina Mueller ’19, Ethan Dieck ’22, Jem Stern ’22, Quin Fraley ’22, Katherine Purev ’23 and Emily Petro ’21—stepped up for a challenge that lasted from April 2019 to March 2020.

The Native American collection was the first to be physically moved; it was the farthest from the new museum (although still only a few blocks away) and had many delicate objects. Comba also wanted to restart that collection’s educational outreach program for third graders, which had been suspended because of the move, as soon as possible. Interns assisted the staff with packing, wrapping and sealing boxes in the basement of Bridges; later the team hand-carried them up by elevator and then carefully loaded and unloaded them in and out of the museum van. Moving the Native American collection took about three months—and countless van rides—to complete.

Hudson made sure that interns knew the protocols of proper object handling, dispelling the myth that the only way to touch museum items is with white cotton gloves. “The cotton fibers of a white glove can snag loose ends of baskets. If you are handling anything fibrous, it could be a disaster,” she says. Nitrile gloves are typically used to handle photographs and prints (they leave no fingerprints), but experts don’t wear them when picking up smooth objects like vases (too slick). Overall, the growing professional consensus is that clean bare hands provide a better and more secure grip, especially when picking up organic items made of stone or bone, such as arrowheads.

Fraley, one of the interns, used her bare hands to check and pack 450 Chinese snuff bottles from the Qing Dynasty, one of her many special assignments. A history major, Fraley recalls getting into a rhythm as she handled the ornate bottles, which ranged in size from 2 to 4 inches. Using poly foam batting, Fraley gently wrapped and nestled the bottles into their drawer-like cubbies encased in pre-cut Ethafoam, a brand of foam often used for artifact storage. As she worked, Fraley examined the intricate details of these ancient mini works of art. “The artist used a fine paintbrush and painted the insides of the bottles,” she says. “It was so special to be able to handle and observe these up close.”

Some heavy or incredibly fragile items, such as Italian Renaissance panel paintings from the Kress Collection, were handled by professional fine art movers.

Comba lost track of how much poly foam was used to securely wrap objects. “It was everywhere,” he says of the material that is firm enough to cushion delicate objects but soft enough not to put unwanted pressure on certain structural elements, like the spout of a teakettle. “You want everything to have a soft landing at every step of the way,” he says.

Items were transported three ways. Heavy and incredibly fragile pieces—like the Kress Collection’s Italian Renaissance panel paintings, a 19th-century marble bust and a Sam Maloof walnut music stand—were given to a professional art-moving company that spent only two days on campus. Most objects, however, were moved using campus vans. Lightweight ones—such as photos, prints, scrolls and manuscripts—were walked over in rolling restaurant-style carts. “It was a huge responsibility, and it was nerve-racking,” Fraley says of those early-morning expeditions. “We just took our time, but I’ll tell you, that short walk never felt so long.”

Days after the last objects were moved to the Benton on March 3, 2020, the pandemic hit. Interns were sent home, which left staffers the final task of checking in and storing those remaining items in their new homes. “We didn’t have a time pressure to finish the job,” admits Comba. “You could call that a pandemic benefit.”

As far as Comba has seen, no item sustained any damage from the moving process, marking this move a huge success.

Now, months after the entire collection has officially settled into its new digs, the reverberations from the relocation still echo for those on the moving team, especially Fraley. “This really opened my eyes to the depth of the moving process and the specialness of this collection,” she says. “Because of this experience, I will never look at any museum the same way ever again.”

The long-awaited Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College opened to the public in May 2021 with reservation-based visits after the planned 2020 opening was delayed by the pandemic.

The long-awaited Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College opened to the public in May 2021 with reservation-based visits after the planned 2020 opening was delayed by the pandemic.

Named in recognition of a $15 million gift from Janet Inskeep Benton ’79, a longtime supporter of the arts and a member of the Pomona College Board of Trustees, the 33,000-square-foot museum provides not only space for the public enjoyment of art but also serves as a teaching museum and a new gathering spot on campus.

The public community celebration planned for November 13 will be preceded by an opening reception and artist talk with Sadie Barnette on November 6 as part of Sadie Barnette: Legacy & Legend. On November 11, the Benton will feature guest curator Karen Kice and graphic designer Amir Berbić as part of Sahara: Acts of Memory. Throughout the fall, the $44 million facility designed by Machado Silvetti Associates and Gensler will host events for the campus community in the museum’s courtyard and striking glass-walled interior spaces.

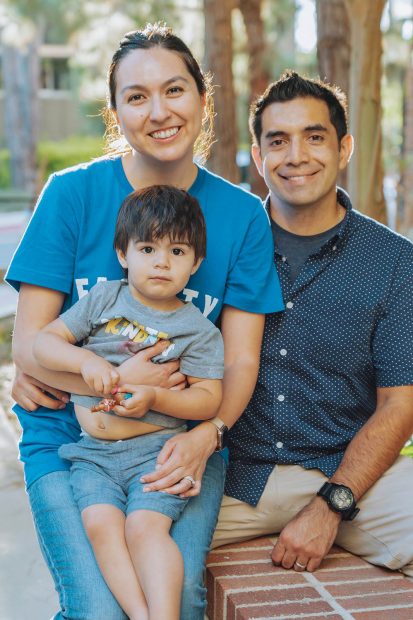

As an inquisitive girl growing up in the city of Pomona, Genevieve Carpio ’05 learned about her world while riding around town with her family. The adults in her life were happy to converse with their captive passenger, especially one so unusually attentive for her age.

As an inquisitive girl growing up in the city of Pomona, Genevieve Carpio ’05 learned about her world while riding around town with her family. The adults in her life were happy to converse with their captive passenger, especially one so unusually attentive for her age.

In the book, Carpio’s first, she examines the history of the Inland Empire through the lens of mobility—the freedom of movement, granted or denied to various racial groups. She focuses on specific policies used to control not just mass immigration, but also the “everyday mobilities” of marginalized, non-white populations.

In the book, Carpio’s first, she examines the history of the Inland Empire through the lens of mobility—the freedom of movement, granted or denied to various racial groups. She focuses on specific policies used to control not just mass immigration, but also the “everyday mobilities” of marginalized, non-white populations.

“It was so wrong,” Carpio says. “I really wanted to understand what it meant, and why it bothered me so much.”

“It was so wrong,” Carpio says. “I really wanted to understand what it meant, and why it bothered me so much.”

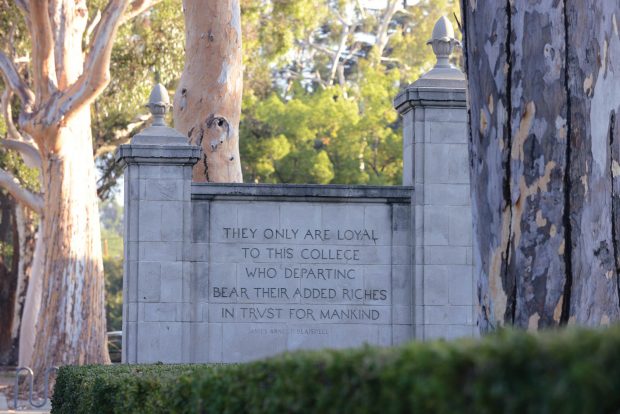

Four years later on her graduation day, Carpio joined her classmates in the traditional passage through the college gates with the weighty inscription: They only are loyal to this college who departing bear their added riches in trust for mankind.

Four years later on her graduation day, Carpio joined her classmates in the traditional passage through the college gates with the weighty inscription: They only are loyal to this college who departing bear their added riches in trust for mankind.

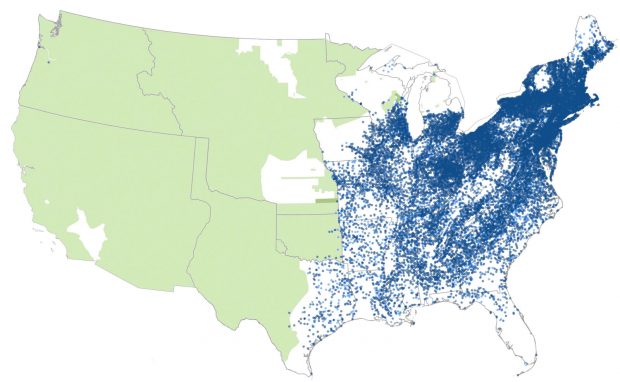

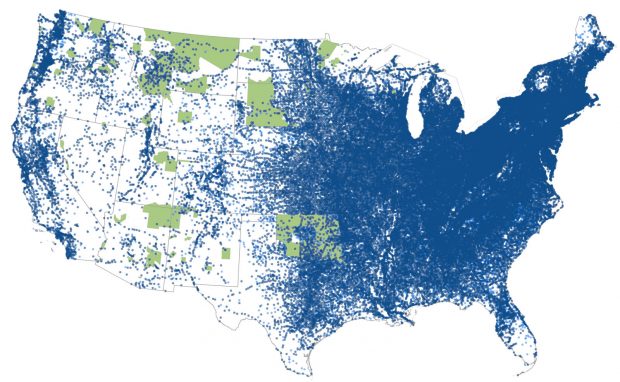

A Wall Street Journal reviewer will go on to call the book “a wonderful example of digital history built on information technology and archival research.” First, though, came the search.

A Wall Street Journal reviewer will go on to call the book “a wonderful example of digital history built on information technology and archival research.” First, though, came the search.

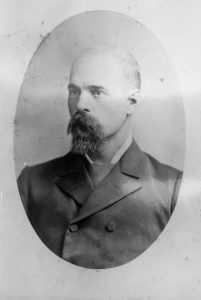

It contained dozens of letters written from the 1850s to the 1890s by Benjamin Curtis and his sisters Sarah, Delia and Jamie. Orphaned in 1852, they had been sent to live with relatives in Massachusetts, Tennessee, Ohio and Illinois. But thanks to the U.S. Post Office, they stayed in touch, especially when they all moved west to equally remote Wyoming, California, Idaho and Arizona.

It contained dozens of letters written from the 1850s to the 1890s by Benjamin Curtis and his sisters Sarah, Delia and Jamie. Orphaned in 1852, they had been sent to live with relatives in Massachusetts, Tennessee, Ohio and Illinois. But thanks to the U.S. Post Office, they stayed in touch, especially when they all moved west to equally remote Wyoming, California, Idaho and Arizona. Lo and behold, in the file Blevins found a photograph of Benjamin, who was far balder than the baby. It was a “humanizing moment” for Blevins as he sifted through the letters offering “beautiful, intimate glimpses” into the siblings’ relationships over decades.

Lo and behold, in the file Blevins found a photograph of Benjamin, who was far balder than the baby. It was a “humanizing moment” for Blevins as he sifted through the letters offering “beautiful, intimate glimpses” into the siblings’ relationships over decades.

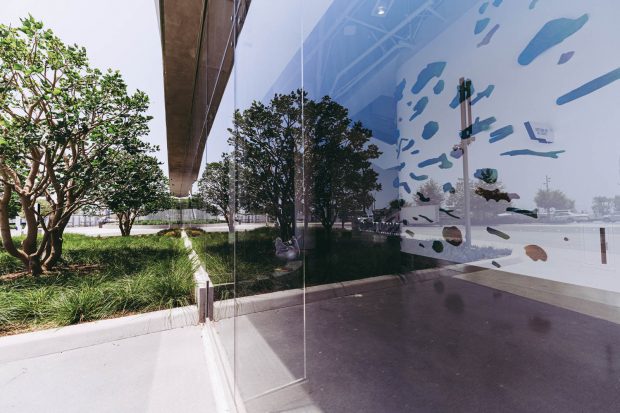

“Luminosity, opacity, color, materiality, texture—all are shifting properties of the work that have an innate architectonic rhythm. I strive to make the experience of moving through the space vivid, transformative and impactful. ”

“Luminosity, opacity, color, materiality, texture—all are shifting properties of the work that have an innate architectonic rhythm. I strive to make the experience of moving through the space vivid, transformative and impactful. ”

“Traditionally we think of space housing the work, but in my case the work communes with space—turning corners, echoing shadows, absorbing light and making room simply for what is there. ”

“Traditionally we think of space housing the work, but in my case the work communes with space—turning corners, echoing shadows, absorbing light and making room simply for what is there. ”

Searching for your next great read? Looking to engage with fellow Sagehen readers? Join the Pomona College Book Club now on PBC Guru. The book club connects Pomona alumni, professors, students, parents and staff to the intellectual vitality of campus. Every two months will bring a new selection to book club members. Then, participants can join their fellow Sagehens in the online forum for prompts and discussion, hosted by our PBC Guru moderator. Members can also look forward to author talks, faculty discussions and more! Sign up at

Searching for your next great read? Looking to engage with fellow Sagehen readers? Join the Pomona College Book Club now on PBC Guru. The book club connects Pomona alumni, professors, students, parents and staff to the intellectual vitality of campus. Every two months will bring a new selection to book club members. Then, participants can join their fellow Sagehens in the online forum for prompts and discussion, hosted by our PBC Guru moderator. Members can also look forward to author talks, faculty discussions and more! Sign up at  Cruz Reynoso ’53, the first Latino to serve on the California Supreme Court, died May 7, 2021, at an eldercare facility in Oroville, California. He was 90.

Cruz Reynoso ’53, the first Latino to serve on the California Supreme Court, died May 7, 2021, at an eldercare facility in Oroville, California. He was 90. As we go to press, students are once again attending classes in Crookshank and Carnegie, Pearsons and Pendleton, the many Seaver buildings and all the other places you remember.

As we go to press, students are once again attending classes in Crookshank and Carnegie, Pearsons and Pendleton, the many Seaver buildings and all the other places you remember.