Jennifer Doudna at work in her lab at UC Berkeley. —Photo by Robert Durell

As word spread around the globe in the early hours of Oct. 7, 2020, that biochemist Jennifer Doudna ’85 had just been awarded a Nobel Prize in chemistry, the honoree herself was sound asleep.

CRISPR on Campus

Pomona students are already using the gene-editing technique discovered by 2020 Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna ’85.

“It’s a little bit embarrassing,” she admitted at a press conference later that morning from the University of California, Berkeley, where she is a professor of biochemistry. Even though—or perhaps because—she had been short-listed for the award by various prognosticators for several years, Doudna hadn’t given the impending announcement so much as a thought when she’d gone to bed that evening. She had even silenced her phone.

“I was awakened just before 3 a.m.,” she added. “My phone was buzzing, and for some reason, it finally woke me up because it turns out it had been buzzing before that, and I hadn’t heard it. But anyway, I picked up the phone and it was Heidi Ledford from Nature magazine, who is a reporter who I know, and she wanted to know if I could comment on the Nobel. And I said, ‘Well, who won it?’”

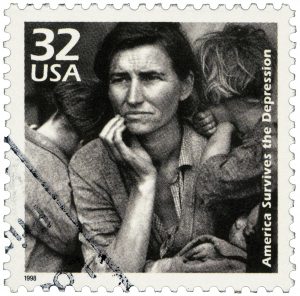

The answer to that question may have surprised Doudna, but it came as a shock to just about no one else in the world of science. In the eight years since she and her research collaborator, Emmanuelle Charpentier—with whom she shares the 2020 award—first described the gene-editing tool known as CRISPR-Cas9, their discovery has taken the world of biological, agricultural and medical research by storm. It has transformed genome editing from a complex, costly, time-consuming and imprecise endeavor into something that can be done with speed, economy and relative precision in just about any modestly equipped research lab in the world. By giving scientists everywhere—in the words of the Nobel committee—“a tool for rewriting the code of life,” Doudna and Charpentier have unleashed a flood of promising new science in everything from agriculture to cancer research, from faster COVID-19 tests to potential cures for such genetic diseases as sickle cell anemia.

By that day in early October, the two chemists had already received just about every other international science award possible, including the $3 million Breakthrough Prize for Life Sciences, the Canada Gairdner International Award, the Heineken Prize for Biochemistry and Biophysics, the Princess of Asturias Technical and Scientific Research Award, the Gruber Prize in Genetics, the Tang Prize, the Japan Prize, the NAS Award in Chemical Sciences, the Kavli Prize in Nanoscience, the Harvey Prize in Human Health and the Wolf Prize in Medicine.

The Nobel Prize came as a giant exclamation point on the end of that list, ensuring that the discovery of CRISPR-Cas9 will be remembered as one of the most significant in the history of science.

And if that sounds like hyperbole, check out this statement from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: “Since Charpentier and Doudna discovered the CRISPR-Cas9 genetic scissors in 2012, their use has exploded. This tool has contributed to many important discoveries in basic research, and plant researchers have been able to develop crops that withstand mould, pests and drought. In medicine, clinical trials of new cancer therapies are underway, and the dream of being able to cure inherited diseases is about to come true. These genetic scissors have taken the life sciences into a new epoch and, in many ways, are bringing the greatest benefit to humankind.”

Jennifer Doudna (right) and Emmanuelle Charpentier receive the Princess of Asturias Award for Technical and Scientific Research from Spain’s King Felipe VI at a ceremony in Oviedo, Spain, in 2015. —AP Photo/Jose Vicente

The Formation of a Nobel Laureate

Growing up on Hawaii’s Big Island, where her father was a professor of English literature at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, Doudna fell in love with nature early on. But hers wasn’t the poetic love of a romantic—it was the analytical love of a budding scientist.

“Father’s big disappointment was I didn’t become a literature guru of some kind,” she said with a laugh. “It’s one of those funny things. It’s just who I am.”

For instance, during the energy crisis of the 1970s, Doudna spent long hours in the school library researching alternative forms of energy, such as geothermal. “I was just always fascinated by science and technology solutions to problems that we face in the world—and never imagined that I would become a scientist until I think I was maybe in 10th grade in high school, when we had a lecture series by people around the state of Hawaii who were professional scientists. A number of really fascinating people came through—marine biologists, volcanologists, astronomers—but the one that really caught my attention was somebody who was working on cancer biology.”

As the researcher talked about her path to becoming a biochemist, Doudna says she felt a light go on. “I thought, ‘That is exactly what I want to do. That sounds so interesting and so fun. I can’t imagine anything more interesting than that.’ That’s why I actually went to Pomona, right? I started thinking, ‘I want to be a biochemist.’ In those days—this is in the late ’70s, I guess, early ’80s, right around 1980—there were not very many undergraduate colleges that had a focus or even a class in biochemistry, much less a major.”

At Pomona, professors like Fred Grieman, who taught the yearlong physical chemistry sequence for seniors, and Sharon Panasenko, who had just been hired to teach biochemistry, would become the first of a series of key mentors who would help shape Doudna’s career. “Mentors are critical,” Doudna told UC Berkeley’s California Magazine. “And fortunately for me, I’ve worked with absolutely outstanding scientists at every stage of my career.”

What set Doudna apart, Grieman recalled, “was her excitement and joy about learning everything.” At times, he said, students can be put off by the challenging nature of chemistry. Not Doudna. “She really enjoyed the rigor and the excitement of learning something that was that difficult—but also something that she could apply later.”

Panasenko—now Sharon Muldoon—has long since retired, but she retains fond memories of Doudna as a junior in her biochemistry class, preparing to enter what was then an intimidatingly male-dominated field. “Most of the students were going to medical school,” she said in a 2017 interview. “Jennifer was one of the few who were interested in a research career, so we talked a lot about it.”Muldoon was so impressed by the young Doudna that she invited her to work in her research lab, studying the bacterial communication systems that permit organisms like Myxococcus xanthus to self-organize into colonial forms. “She really showed a tremendous amount of aptitude and talent for lab work, which certainly helps if you’re going into a research career.”

Doudna remembers being astounded to have been chosen to work in Muldoon’s lab in the first place. “I got this opportunity to work with her over the summer, and really work with her,” she recalled. It wasn’t just that she threw something over the fence and said, ‘Come back in 10 weeks when you’re done.’ It was every day, going in and planning out experiments with her, and it was just the most amazing thing.”

Doudna still cites her Pomona education as a key ingredient in her success. “I am grateful to Pomona every day, honestly,” she said, “because it was a liberal arts education that exposed me to so many ideas that I would never have come in contact with, probably, without having attended Pomona.”

After Pomona, she earned her doctorate at Harvard under the supervision of geneticist Jack Szostak, who later won the Nobel Prize in medicine. It was under his tutelage that she began working with ribonucleic acid (RNA), the biochemical cousin of DNA, which she has continued to study throughout her career. She then did a postgraduate fellowship with another Nobel laureate, chemist Thomas Cech of the University of Colorado, Boulder, and went on to teach at Yale University. In 2002 she returned to California as a professor at UC Berkeley, where she now holds the titles of professor of chemistry, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, and the Li Ka Shing Chancellor’s Chair in Biomedical and Health Sciences.

A former member of the Pomona College Board of Trustees, Doudna has been back to campus many times since graduating. Most notably, she returned in 2009 as the featured speaker for the Robbins Lectureship, which has brought to campus a veritable who’s-who of the world’s preeminent chemists, including a number of Nobel winners. The news that Doudna would be joining that exalted group of laureates—becoming the first graduate of Pomona College ever to receive a Nobel Prize—was met throughout the college community with an outpouring of Sagehen pride.

“Jennifer Doudna’s revolutionary research in gene editing and her thoughtful consideration of its implications hold the potential to change the lives of countless people around the globe,” said Pomona College President G. Gabrielle Starr. “We are so proud that she received her undergraduate education at Pomona College and that she continues to engage in the life of our community. Her sense of discovery, her commitment to rigorous work and her willingness to reflect on its meaning embody some of the highest values of the College.”

Early on Nov. 7, Jennifer Doudna sits on her patio, taking congratulatory calls. —Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small

The Aha Moment

It’s hard to say where the road to discovery begins, but a conference of the American Society of Microbiology in Puerto Rico in the spring of 2011 is as good a starting point as any. That’s where Doudna, a biochemist specializing in the study of RNA, met Charpentier, a French microbiologist studying how bacteria cause disease.

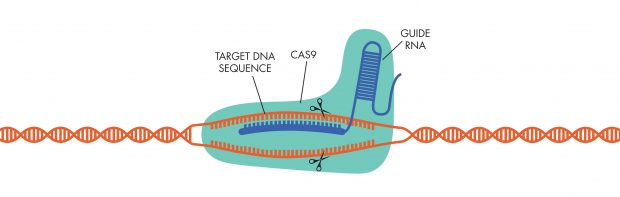

Both, as it turned out, were intrigued by a type of genetic sequence in bacteria known as CRISPR—which stands for “clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeat.” These odd DNA sequences play a key role in a bacterium’s first line of defense against viruses by allowing it to recognize and cut up viral DNA. Charpentier had already demonstrated that RNA played a key role in that process, so it made sense for her to ask RNA expert Doudna if she’d like to team up. Doudna, impressed by Charpentier’s passion for her work, immediately said yes.

“We decided there to start working together on one particular element in the CRISPR pathway, a protein called CRISPR-Cas9 that, at the time, was clearly important for protecting bacteria from virus infection, but nobody knew how it worked,” Doudna explained. “And so that was the question we set out to investigate.”

Working with Doudna’s postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, Martin Jinek, and Charpentier’s research student, Krzys Chylinski, they began to do experiments. One discovery led to another, and Doudna still remembers the aha moment when she realized how important CRISPR-Cas9 could be.

“Martin Jinek in the lab had done experiments showing that not only could we control the DNA sequence where Cas9 would make its cut in the double helix, but also that we could engineer it to be a simpler system than what has been done in nature,” she recalled. “And I think—you know, I remember that moment very, very clearly—that Martin Jinek was in my office, and we were talking about his data. And we looked at each other, and we realized that this could be an extraordinary tool in other kinds of cells because of its ability to trigger DNA repair, and thereby to trigger genome editing. And that really set us on a course that has been just amazing over the last eight years after publishing that original work in 2012.”

That first article, published in the summer of 2012 in the journal Science, one of the world’s foremost scientific publications, exploded onto the scientific scene like a Fourth of July rocket. Within a year and a half, labs around the world had confirmed that CRISPR-Cas9 was a truly revolutionary discovery. As Adam Rogers ’92 wrote in his 2015 article about Doudna and her discovery for PCM, “Not only was CRISPR a quick-and-easy way to edit a genome as easily as Word edits a magazine article, but it worked in just about every living thing—yeast, zebrafish, mice, stem cells, in-vitro tissue cultures and even cells from human beings.”

That’s what you call revolutionary. But as Doudna would soon discover, it can be just as hard to rein in a revolution as it is to start one.

Later that morning, Doudna sits in a studio at UC Berkeley taking Zoom questions from reporters around the world. —Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small

The Accidental Ethicist

It’s easy to see the almost infinite possibilities for important and beneficial science embodied in the CRISPR revolution. The most compelling of these for Doudna is the potential for curing a range of terrible genetic diseases.

“When I was in graduate school in the 1980s, my lab was located at the Massachusetts General Hospital, where a professor named Jim Gusella was mapping the gene that causes Huntington’s disease, which is a terrible neurodegenerative disease that people get usually in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and then they suffer from it for many years with sort of progressive loss of neurological function,” she recalled in an interview for PCM. “And so being aware of that gene-mapping experiment that was done in the ’80s, and then fast-forwarding a couple of decades and realizing that now there was this technology that, in principle, will allow correction of that kind of mutation is really a profound thought.”

However, there’s another side to the CRISPR revolution that Doudna hadn’t anticipated.

Previously, the two preferred techniques for gene editing—“zinc-finger nucleases” and “TALEN”—required the creation of custom-engineered proteins that were challenging to make and difficult to use. Buying one could set you back $25,000. Quite simply, the state of the art acted as a brake on the ambitions of aspiring gene editors everywhere.

Enter CRISPR. Today, a starter kit for using this relatively simple and precise technique costs about $65, plus shipping. Suddenly scientists all over the world have the tools in their hands to rewrite any gene they wish, pretty much at will.

What could possibly go wrong?

“People are people,” Doudna said in a recent interview. “If you have a powerful tool, there is some type of person that wants to use it for whatever—anything, right? Anything that can be done should be done. I think that CRISPR’s been no exception to that. What we’ve seen with CRISPR over the last few years is that there are a couple of things that’ve been done with CRISPR that are clearly, I think, irresponsible and shouldn’t be done. One of them, probably the one that got the most attention, was CRISPR babies.”

What she’s referring to is Chinese researcher He Jiankui’s announcement in 2018 of the birth of twin girls whose genomes he had altered in vitro using CRISPR. This shocking bit of news ratcheted up the ethical debate around the use of CRISPR and, a year later, landed the researcher himself in prison, with a three-year sentence for “illegal medical practices.”

Doudna’s reaction to all of this was clear: “Using CRISPR to change the genetics of human embryos, not for research but for actual implantation and to create a pregnancy—I think that clearly is something that just, at least right now, shouldn’t happen, because the technology isn’t ready, and we’re not ready, right? Society isn’t ready for that.”

But where should the lines be drawn?

Long before He’s ill-fated foray into designer babies, Doudna had decided that her personal responsibility in these matters went far beyond simply publishing her work. “I went from being a biochemist and structural biologist, working in my lab on this esoteric bacterial system, to realizing that I needed to get up to speed quickly on how other kinds of technologies that have been transformative had been managed and handled by the scientists that were involved in their genesis. Because things were moving so quickly that the ethical discussions needed to get going very fast.”

In 2015 Doudna organized a meeting of top biologists to discuss these issues and became the lead author of their report—also published in Science—calling for a moratorium on the use of CRISPR to edit the human genome in heritable ways. Her concerns also helped shape the book she was working on at about the same time. A Crack in Creation: Gene Editing and the Unthinkable Power to Control Evolution, published in 2017, wasn’t just the story of a groundbreaking discovery and its potential benefits—it was also an exploration of the ethical dilemmas involved in controlling irresponsible use of that breakthrough.

“What I worry about the most,” she explained, “is a rush to apply genome editing in ways that might harm people—because of over-excitement or the desire on the part of a scientist somewhere to do something first. I think that can be a very healthy drive in science, or in anything. In human endeavors, you know, people are competitive, and they want to move ahead with things and move ahead with ideas. I think it can also lead to problems, and in this case, I really hope that there’s a concerted effort globally to restrain ourselves and do things in a measured and thoughtful fashion that doesn’t get ahead of the technology or ahead of the ethical debate.”

Doudna raises a glass of champagne as she celebrates with her research team. —Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small

Of Patents and Pandemics

From the start, one key question has remained unanswered, and even now, eight years later, it still hangs in the legal balance.

Who owns CRISPR?

In a world where seemingly every scientific breakthrough gets monetized, that’s a very important question. Over the past few years, the competition for the legal rights to this revolutionary technology has pitted two main camps against each other in a series of courtroom battles. On one side is a group known as CVC, led by UC Berkeley and based on the work of Doudna and Charpentier. On the other is the Broad Institute at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), based on the work of MIT researcher Feng Zhang, who published his own work on CRISPR seven months after Doudna and Charpentier, but with one key addition—evidence that it could be used to alter genes inside eukaryotic cells, the kind that make up all plants and animals.

Though Doudna and Charpentier were the first to publish about CRISPR-Cas9, Zhang’s team was the first to obtain a patent. Since then, competing claims have been caught up in the byzantine complexities of patent law, as adjudicated by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, which has seemed to try the Solomonic approach, cutting the CRISPR baby in half and granting each side a piece of the action. This has left a rather confusing dividing line between the two claims while leaving the door open to further challenges. As a result, it’s still hard to say exactly who owns what.

In the meantime, startups galore have taken CRISPR and run, doing science that has the potential to improve people’s lives while banking on future profits. Doudna herself is the founder or co-founder of four startups now focusing on areas of research ranging from diagnostic tests to gene therapies. Other firms are trying to use CRISPR to detect genetic mutations, create customized plants and even grow human-compatible organs inside pigs.

So it’s no surprise that CRISPR is already playing an important role in COVID-19 research.

Way back in March, Doudna pivoted in her work to seeking ways to play a constructive role in bringing the pandemic to heel. “When it was clear that we were facing a global emergency with this pandemic back in the early part of this year,” she explained, “many of us asked ourselves, ‘What could or should we be doing to use our own expertise in this time of real need?’”

Her immediate answer was to start a clinical testing lab for the virus through the Innovative Genomics Institute, where she is president and board chair. “We also raised quite a bit of donor support for this,” she noted. “Because of that, we’ve been able to offer this test for free to many people in the East Bay Area of California, where quite frankly, many of those folks don’t have access to health care. They don’t have access to testing. A lot of our partner health care organizations service the unsheltered, the uninsured folks that are first responders, people that work in the California energy sector that are keeping our power plants running, police, firefighters, people working in nursing homes.”

Those tests don’t involve CRISPR, but research on CRISPR-based tests is ongoing. And just two days after the Nobel announcement, a new article in Science revealed that one of Doudna’s research teams has developed far and away the fastest diagnostic test for the novel coronavirus yet. Though this CRISPR-based test is not yet as sensitive as tests that take a day or more to process, it can detect the virus in five minutes flat. And it can also do something else that no other test can do—quantify the amount of virus in the sample, potentially enabling doctors to tailor their treatment to the severity of the patient’s infection.

Eyes on the Prize

On Dec. 10, there will be a big celebration in Stockholm, Sweden, with fanfare befitting a new bevy of Nobel laureates. When Doudna and Charpentier receive their award—whether or not the pandemic permits them to actually step onto the stage to accept their medallions from the hands of King Carl XVI Gustav of Sweden—it will be the first time in history that two women have shared the prize in chemistry.

The monetary value of the prize they will share is 10 million Swedish krona, a bit more than $1 million. However, its value in terms of prestige and history is incalculable. Patents and startups may come and go, but a Nobel Prize is forever.

For Doudna, however, the reward is still in the work.

“I still, in my heart, think of myself as that young girl growing up in Hilo and thinking to myself, ‘Gosh, I wonder if I could be a biochemist someday.’ I still think of myself that way, right? Honestly, I still have moments when I look around at my colleagues and the people I’m so lucky to work with every day, and I think, “Wow, I’m so lucky.’ I just feel grateful. For me, that’s what it’s about. It really is. It’s about doing work that I enjoy, where I feel like I’m making a contribution.”

Still, they run.

Still, they run. 1. Grow up in Paradise. Before it was largely destroyed by the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in state history, Paradise, California, was a town steeped in the yo-yo culture of nearby Chico, home of the National Yo-Yo Museum.

1. Grow up in Paradise. Before it was largely destroyed by the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in state history, Paradise, California, was a town steeped in the yo-yo culture of nearby Chico, home of the National Yo-Yo Museum.

In July Pomona College welcomed Nathan Dean ’10 as the new National Chair of Annual Giving. Nathan will serve a two-year term as the College’s primary proponent for annual giving and as an ex-officio member of the Board of Trustees.

In July Pomona College welcomed Nathan Dean ’10 as the new National Chair of Annual Giving. Nathan will serve a two-year term as the College’s primary proponent for annual giving and as an ex-officio member of the Board of Trustees. our new Director of Alumni and Parent Engagement

our new Director of Alumni and Parent Engagement

In his career, Ronald Lee Fleming ’63, P’04, author of the newly published The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener: Creating a Landscape of Memory, worked hard as an urban planner, preservationist and innovator, doing Main Street revitalization projects in small towns even before the National Trust for Historic Preservation took them on. In fact, Fleming says, he was once told, “Well, we’ve copied everything you ever did.”

In his career, Ronald Lee Fleming ’63, P’04, author of the newly published The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener: Creating a Landscape of Memory, worked hard as an urban planner, preservationist and innovator, doing Main Street revitalization projects in small towns even before the National Trust for Historic Preservation took them on. In fact, Fleming says, he was once told, “Well, we’ve copied everything you ever did.”