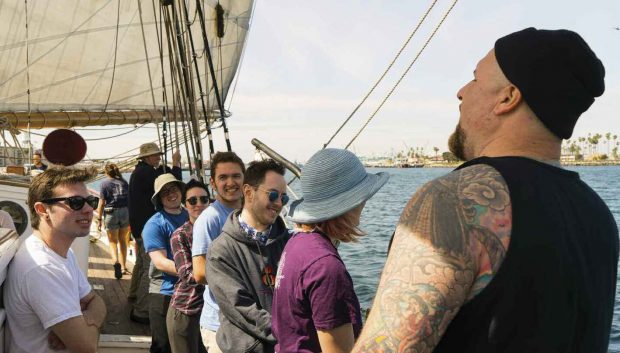

Professor of Music Gibb Schreffler (right) and class aboard the Exy Johnson. Photo by Lushia Anson ’19

TO HELP HIS students get on board with one of his chief research interests, Music Professor Gibb Schreffler got them out of the classroom and out to sea.

On a breezy spring afternoon, aboard the two-masted sailing vessel Exy Johnson in Los Angeles’ San Pedro Bay, Ranzo—Schreffler’s chantyman alter ego—led a group of Pomona and Claremont Colleges students in singing “Goodbye, My Riley” and “Tom’s Gone a Hilo,” traditional work songs known as “sea chanties.” Adding the physical labor and rhythm of pulling halyard lines gave the students a sense of how chanty singing once fit into the work of the crew on a traditional sailing vessel. As the hoists grew more difficult toward the end of the lines, the chanty leader shifted to a “short drag” chanty such as “Haul Away, Joe” and “Haul the Bowline” to reflect the cadence of a more demanding physical effort.

The half-day sailing field trip was part of Schreffler’s special topics course, American Maritime Musical Worlds, where his class explored America’s musical development from the perspective of those who have lived or worked near the water. The goal was to better understand the context and function of the shipboard work songs prevalent in the 19th century.

According to Schreffler, the topic of American maritime music is not well-documented or researched. His scholarship focuses on the musical experiences of African Americans, and his findings place the tradition of sea chanties within the larger umbrella of African American work songs. The epicenter of the chanty genre, he explains, was not Great Britain but America—or, more precisely, the western side of the “Black Atlantic,” rimmed by Southern U.S. ports and the Caribbean.

Schreffler’s research also found that chanty singing by sailors at sea represented just one branch of a larger network of work-singing practices, most of which were performed on terra firma. In fact, far more chanties were sung by stevedores—the workers loading ships—than were ever sung by sailors. Sailors’ labor tended to be associated with white workers, and stevedores’ labor was associated with Black workers—which partly explains the neglect of the latter’s story in ethnocentric narratives told by English and Anglo-American authors of the last century.

Schreffler’s research has been challenging, in part, because much of what has been presented in the last century has created a strong bias against recognizing African Americans as creators of the sea chanty genre. His published work on the subject includes the article “Twentieth Century Editors and the Re-envisioning of Chanties,” in the maritime studies journal The Nautilus.

His research takes him to archives and ports in cities around the country that were centers of maritime commerce, such as Mobile, Alabama, and Galveston, Texas. He also has traveled internationally in a traditional sailing ship from the Azores, in the middle of the Atlantic, to the coast of France, to study applied seamanship in order to better understand the historical texts he studies.

Since the maritime work songs Schreffler studies are not used in today’s sailing, recreating their performance helps him imagine them and find answers, despite the lack of detailed information available. Since 2008 he has been working on posting online his renditions of every documented chanty song he has encountered. His purpose for the recordings is to simulate psychologically the process of acquiring a repertoire and learning the genre’s method and style.

“Scholars in my field, ethnomusicology, traditionally employ fieldwork to interpret living culture as ‘text,’” he explains. “In order to study culture of the past in this fashion, I try to convert history into a sort of living text in the present.”

Last spring was his first time teaching the course, but Schreffler previously brought chanties to Pomona College and The Claremont Colleges through the Maritime Music Ensemble he founded and directed in 2013. In the ensemble, all songs were taught orally to simulate a realistic way of acquiring the tradition. Students needed no prior formal training and took part in engaging sessions of rehearsals or jam sessions as well as performances.

Experiencing music in order to understand it is at the core of Schreffler’s teaching and research. Also a scholar of the vernacular music of South Asia’s Punjab region, he learned to play the large drum known as the dhol. “Without my doing this, many of my interlocutors would have had no idea how to relate to what I was doing in studying Punjabi music,” he says.

Schreffler has plans to return to his Punjabi research and work on a forthcoming book during his upcoming sabbatical year. In addition, he headed to the Caribbean during the past summer to get reacquainted with the Jamaican music scene in order to prepare his next spring course. Among the topics he will explore in that class, he says, is the connection of Jamaican music to the beginnings of hip hop and electronic music.

“Some of my students are very interested in producing or becoming DJs, so this course could be of special interest to them, given the connection to the origin of hip hop and dance music.

“My goal with this class, as in all of my classes, is to give them information and lively discussion that will challenge them about something that is related to a topic they’re interested in to begin with. I don’t necessarily tell them that it is related, but I drive them to make the connection. Once they see the connection, it transforms their learning about the original topic of the class.”