Bryan Kevan ’14 at the Mirador Cuesta del Diablo, just off the Portezuelo Ibañez, the highest pass on the Carretera, in 2014.

IF A ROAD can be a political statement, then the Carretera Austral—stretching 1,200 kilometers, the majority of the length of Chilean Patagonia—is just that. Started under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in the 1970s, it checked all the boxes for a military dictator seeking to exert political and economic control over the country’s most remote and inaccessible territory.

Many of the towns along the road had previously been connected to the outside world only through towns across the border in Argentina, a dependence that Pinochet sought to eliminate. Snaking around narrow fjords, over high mountain passes and through dense, seemingly impenetrable forests, the road was a symbolic statement that not even nature could stop Chile from policing its borders. The road unofficially carried Pinochet’s name for years, an indication of its strategic military importance in the historically poor relationship between Chile and its neighbor to the east.

As Pinochet’s reign continued, so did construction of the Carretera Austral. Over decades, the road inched farther and farther into the Patagonian wilderness. Signs along the road still carry a Ministry of Public Works slogan harkening back to the road’s original political significance: “Obras que Unen Chilenos” (“Works That Unite Chileans”).

The spirit of the Carretera Austral remains, embedded in a thin ribbon of gravel road connecting Chilean Patagonia to the rest of the country. In 2000, workers finally reached their limit, a dead end at the town of Villa O’Higgins. The terrain was just too rough after that point, and the territory too remote. With no more towns, the Carretera Austral had reached its terminus. Two small border crossings into Argentina, complete with posts and military barracks, were constructed at the end of the road, neither passable by car.

When I graduated from Pomona in 2014, my mom told me to go out and take a new risk. Confined to the Pomona bubble for four years, and to the bubble of small Eugene, Oregon, for my life before that, I was hungry for something different. Something new, challenging and, most importantly, something not academic. I didn’t, and still deep down don’t, consider myself particularly athletic or adven- turous. I ran cross-country in high school, but not particularly well. I enjoyed hiking and camping, but it was clear at least to me that I didn’t share the single-minded passion for it that many of my classmates had. I replied to my mom over text with a picture of a motorcycle, and she responded with a picture of a bicycle. It was decided.

So I packed up the things I thought I would need for a few weeks on the road, never having camped for more than a handful of nights in a row, and set off to Patagonia. Everyone on the Internet’s various bike-touring forums raved about this gravel road in Chile, and I felt like I just had to do it. I didn’t expect to make it far. Maybe go out for a week or two, have a fun experience and then come back.

I quickly realized upon my arrival that I had timed it all wrong. It was September, very early spring in Patagonia, and most towns, campsites, hostels and even some border crossings into Argentina were still closed. It rained pretty much constantly for the first two weeks of my trip, and the state of the road left my body broken and bruised every night from hour upon hour of riding on rocky, muddy gravel.

My tent was hardly waterproof, my rain jacket even less so. For a road that was supposed to be so popular with touring cyclists, it was surprisingly little-traveled; I finally saw another cyclist after a month. It was a struggle. I learned to live with myself, camped alone for weeks in the middle of nowhere. But it was exciting, it was new, and I loved every second of it.

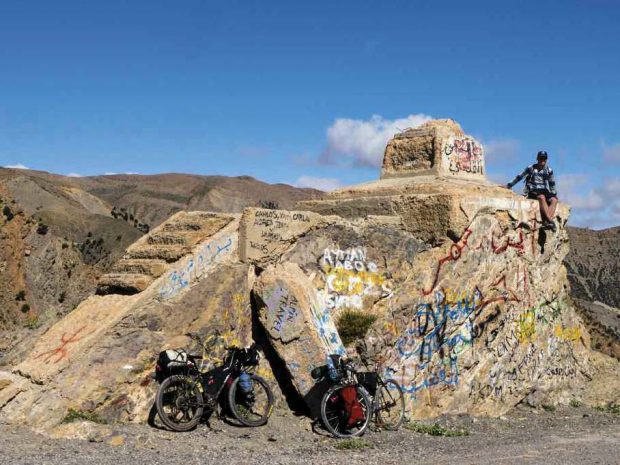

Kevan sitting on a marker identifying the peak of the Tizi n’Isli Pass while riding along the spine of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco in 2017.

At Villa O’Higgins, a month into my trip, I reached the dead end, and the two roadless border crossings, only one of which was open during that season. The Chilean post was unassuming, to say the least—just two small buildings and a helipad at the dead end of a rough gravel road. Three policemen manned the post, sitting around a fireplace stamping passports and making snide remarks about the Argentines 15 kilometers away. I stayed the night in the barracks next to a nice, warm fire and stamped out of Chile the next morning. Between passport stamps, it took 14 hours of navigating the roadless swamp of backwoods Patagonia to reach Argentina. I cursed and yelled my way through dense forests, over swinging sheep bridges, through bogs and through glacial streams, all on the very imprecise directions received from a very inebriated gaucho living on the border.

I eventually found a road that led to the Argentine border post. As I stumbled out of the wilderness, a policeman came out to meet me, clearly concerned for my safety. I was quickly stamped into the country and shown where to set up camp.

In a poetic turn, I experienced the same thing at the Argentine border as I had at the Chilean one, but in reverse—just three policemen stamping passports and making snide remarks about Chileans. After the decades of antagonistic relations and political symbolism that surrounded the road’s construction, all that remained at road’s end was a remote border crossing, a few half-rotted military barracks and a handful of policemen taking half-hearted verbal shots at one another across the border.

I was sold. These were the genuine travel experiences I wanted in my life. I continued my trip, eventually ending up in Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America. More trips soon followed—Southeast Asia, the Pacific Northwest, Iceland, and Morocco, all since graduation.

I am now in the planning stages for a trip spanning the entirety of the Silk Road across Central Asia, starting in 2018. I encourage interested readers to follow along at my blog starting next March at venturesadventures.wordpress.com.”