The Farallon Islands, a windy string of rocks 30 miles off the coast from San Francisco, might seem like an odd place to call a “second home.” Boasting just a single research station, the remote islands are only accessible by infrequent and often choppy boat trips. But Associate Professor of Biology Nina Karnovsky isn’t fazed by the rugged conditions.

“It’s one of my favorite places in the world,” she says.

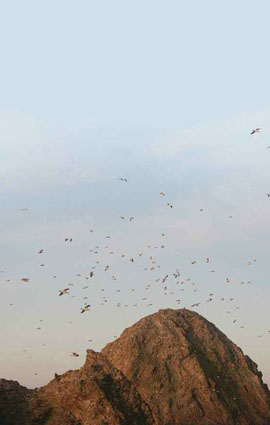

Home to the largest seabird colony in the continental U.S., the Farallones are a magnet for ocean wildlife. In summer, seemingly every inch of the place is claimed by thousands of nesting birds fiercely guarding their chicks. During the winter, noisy elephant seals crowd the beaches to give birth to their pups. Meanwhile, great white sharks hunt in the waters offshore. In other months, blue and humpback whales can be spotted making their annual migrations along the coast. Karnovsky made her first trip to the islands when she was just out of college, to work on a project to record shark sightings.

Home to the largest seabird colony in the continental U.S., the Farallones are a magnet for ocean wildlife. In summer, seemingly every inch of the place is claimed by thousands of nesting birds fiercely guarding their chicks. During the winter, noisy elephant seals crowd the beaches to give birth to their pups. Meanwhile, great white sharks hunt in the waters offshore. In other months, blue and humpback whales can be spotted making their annual migrations along the coast. Karnovsky made her first trip to the islands when she was just out of college, to work on a project to record shark sightings.

She’s returned several times over the years to observe how seabirds such as auklets and gulls respond to changing conditions in the ocean. Perched at the top of the marine food web, these birds are impacted by everything from climate events like El Niño to pollution from plastics and oil spills.

“On my second trip out there, during a seabird breeding season, I realized that these birds are just such powerful indicators of what’s going on in the ocean. That really turned me on to the idea of using these indicator species in my work, and that’s exactly what I do now,” she says.

A National Wildlife Refuge since 1969, the Farallones are closed to the public, and scientists and students are only allowed for temporary visits. Still, wildlife-lovers can catch a close view of the action from birding and whale-watching boats that sail from cities in the Bay Area to circle around the islands.

“If you’re not susceptible to sea-sickness, you can go out there and see them,” Karnovsky says.

Karnovsky, who has spent over a year’s worth of time on the Farallones between her different stays, hopes to ship out again soon. In recent years she’s even been able to send some of her students to the islands to gather data for their own summer research projects and senior theses.

“Looking back, I can see it was one of the turning points in my life, where I discovered something that was really exciting. It’s nice that I’ve been able to share that with my students.”