On December 2, a group of large, athletic men will walk onto the court of AT&T Center in San Antonio. Five of them will wear the red-and-blue uniform of the Hawks, a mostly-middling NBA franchise from Atlanta. The other five will wear the black-and-silver of the San Antonio Spurs, perhaps the most successful franchise in modern pro sports. In most respects, it will be just another early-season, midweek game on the NBA schedule. But for the two not-so-large, suit-wearing men standing in front of each team’s bench, it will be a historic, and no doubt emotional, moment. After 19 years on the same sideline, Mike Budenholzer and Gregg Popovich will coach against each other for the first time.

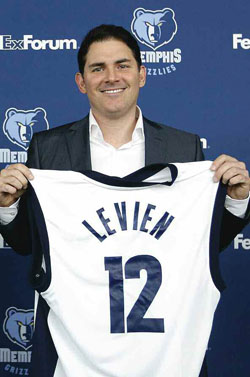

Six hundred-odd miles to the northeast, Jason Levien will be watching. Levien is the general manager of the Memphis Grizzlies—an NBA team which, he prefers you don’t remind him, was swept by the Spurs in the Western Conference Finals during last season’s playoffs. The Grizzlies won’t be playing on that Monday, so Levien might be at home or, perhaps, on the treadmill, where he often ends up on game nights, too nervous to sit and watch. He logged eight miles in the second half of a single Grizzlies playoff game last spring.

Since this is an alumni magazine, you’ve probably guessed what connects these three men, but that doesn’t make it any less remarkable. The chances that two NBA head coaches and one NBA GM—the ultimate decision-maker for a franchise and one of the hardest jobs to attain in sports—would all come from one Division III, liberal arts college are infinitesimal. But there they are: Popovich, the Pomona-Pitzer head coach for eight years, ending in 1988; Budenholzer, a Pomona-Pitzer shooting guard, class of ’92; and Levien, Pomona-Pitzer reserve guard, class of ’93.

Just as expected, the Sagehens have overtaken the NBA.

FIRST, SOME BACKGROUND. As it turns out, I have an unusual perspective on all this. In the fall of 1992, I transferred into Pomona as a sophomore, hoping to play on the basketball team while preparing for a career in journalism. Mike was one of the first players I met. He made quite an impression. One memory stands out: an informal pickup hoops game at Rains Center, early that fall. Most of the team was there.

FIRST, SOME BACKGROUND. As it turns out, I have an unusual perspective on all this. In the fall of 1992, I transferred into Pomona as a sophomore, hoping to play on the basketball team while preparing for a career in journalism. Mike was one of the first players I met. He made quite an impression. One memory stands out: an informal pickup hoops game at Rains Center, early that fall. Most of the team was there.

As one of a handful of point guards hoping to make the varsity squad, I was matched up against Mike, a senior and starter on the team. There was no coach. No audience. Just a bunch of young men getting in shape before the season.

Mike’s team scored first. I took the inbounds pass and turned to dribble up court. That’s when I saw Mike, 70-odd feet from the opposing basket, standing directly in front of me, hands in a defensive posture, eyes wide, face a contorted mask of intensity. And so it went, for the rest of the afternoon. In a pickup game, in the preseason, Budenholzer picked me up and defended me full-court on every possession, as if it were the NBA Finals.

At the time, it was shocking; playing full court defense in a pick-up game is akin to bringing your own backing band to karaoke night. Later, though, it would make perfect sense—once I learned that Mike’s father, Vince, was a longtime high school coach, so successful that in 2005 he was inducted into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame. And that Mike was the seventh of seven children, and the fifth boy. And that, though born with neither exceptional athleticism or size— he stood 6’1” and was never a leaper—Mike had succeeded at every level of the game. He did so, I learned, by wanting it more than anyone else on the floor.

I met Jason next. Immediately, he stuck out. Amid the tall, gangly players trying out for the team, Jason was an anomaly: relatively short and neither quick nor springy. Instead, he was clever and efficient. He’d transferred in the season before, his sophomore year, from Georgetown. Though not a regular rotation player, he’d enjoyed a few big moments: playing important minutes against CMS, hitting four three-pointers against Caltech.

From the start, he struck me as a born politician, in the best sense of the word (if there is such a thing). He was intelligent, gregarious and possessed the rare and valuable trait of being genuinely curious about other people’s lives. As preseason wore on, the two of us were paired up as workout partners. We lifted weights, sweated through drills and, most memorably, shot an endless succession of free throws. Every player on the team was expected to make 1,500 before the first official practice. Our reward: a T-shirt that read The 1,500 Club. I believe mine is in the garage somewhere, in a box underneath the ping-pong table.

The team was talented that year. Mike was the heart and soul—the coach on the floor—but Bill Cover ’94 was the star. Six-foot-six and fundamentally sound, Cover was a deadly midrange shooter and the team’s go-to option on offense. He would end up graduating the following year as the Sagehens’ all-time leading scorer (a distinction he still holds). The team also featured Paul Hewitt, 6’6” and lanky; Brian Christiansen, a deadeye shooter whose range extended seemingly to the bleachers; Alden Romney ’96, a blonde, toned swingman who looked like he should be on Baywatch; and Phil Kelly ’95, a quicksilver, lefty point guard. The coach, then as now, was Charles Katsiaficas. A disciple of Popovich, he’d been an assistant for years before taking over the head job full-time in 1988. (None of the players on the 1992–93 team played for Pop, though Budenholzer, who was a fifth-year senior, had been recruited to Pomona by the coach in 1988).

The season came to an unsatisfactory end. The varsity finished 16–9 overall and 9–5 in SCIAC but missed the playoffs. Mike played well, averaging 5.4 points per game, 3.04 assists and leading the team with 44 steals in 25 games. Meanwhile, Jason and I spent the great majority of our time toiling on the junior varsity. There were highlights—overtime wins and postgame breakdowns and poker games and, for me, a lone collegiate dunk, which I have since treasured as one might a family heirloom. That it came against Caltech and that I traveled on the play are neither here nor there. We take what we can in life. As for Jason, he finished his Pomona varsity career with what has to be one of the highest three-point percentages in school history: 62.5 percent. He took eight shots from behind the arc and made five.

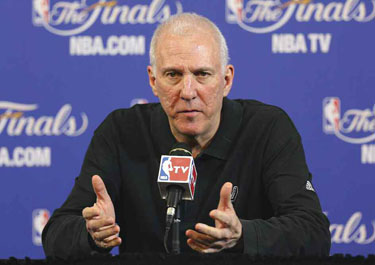

OF THE THREE, Popovich’s NBA ascent occurred first. His story is also the best-known. At Pomona, he turned around the Sagehen program, taking a team that was 2-22 in his first season and, within six years, leading it to a SCIAC title and a NCAA Division III Tournament berth. After spending a year as a volunteer assistant to Larry Brown at Kansas, he rejoined Brown with the Spurs, as an assistant. After a stint with the Golden State Warriors, he ended up back in San Antonio, and eventually became the general manager. In 1996, he named himself head coach. It’s a title he’s held ever since.

OF THE THREE, Popovich’s NBA ascent occurred first. His story is also the best-known. At Pomona, he turned around the Sagehen program, taking a team that was 2-22 in his first season and, within six years, leading it to a SCIAC title and a NCAA Division III Tournament berth. After spending a year as a volunteer assistant to Larry Brown at Kansas, he rejoined Brown with the Spurs, as an assistant. After a stint with the Golden State Warriors, he ended up back in San Antonio, and eventually became the general manager. In 1996, he named himself head coach. It’s a title he’s held ever since.

Mike first worked for Pop at Golden State when he asked to “observe” the team. Pop told him he could work in the video room. He wouldn’t be paid, and he shouldn’t talk to anybody. Just do the film and go home. Budenholzer jumped at the chance. A couple years later, after Mike spent a post-grad season playing and coaching for Vejle Basketball Klub in Denmark, where he averaged 27.5 points, Pop called with a real job offer: video coordinator in San Antonio. It was almost as unglamorous as his first position. In the pre-digital age, Mike’s job was to hand-splice together VHS tapes of upcoming opponents in a small, dark room. Still, when I came through town in the summer of 1996, it was clear Mike was happy. At the time, I was writing a book about playground basketball, and the reporting took me around the country (two other Pomona grads from the class of 1995, Eric Kneedler and Craig Harley, came along to help with the research). When we stopped in on Mike, he was living decidedly low on the hog. In particular, I remember that he’d somehow accumulated a treasure trove of free sandwich coupons from Subway. As far as we could tell, he was living off them while working in that dark cave. No matter: it was the life he wanted. And it paid off. That fall, Pop elevated Budenholzer from video coordinator to the team’s lowest- ranking assistant coach. He was on his way.

Meanwhile, Levien followed a more unconventional path to the NBA. He attended law school at the University of Michigan, worked as a campaign consultant (writing Tennessee Congressman Harold Ford Jr.’s keynote speech at the 2000 Democratic Convention in Los Angeles) and, eventually, seguedt into the position of sports agent. After a number of high profile signings, including inking Miami Heat forward Udonis Haslem’s $33 million contract, he was featured in an article in this magazine titled “Show Me the Money.” He later brokered an $80 million deal for Chicago Bulls forward Luol Deng.

Meanwhile, I meandered on my own path toward, or at least near, the NBA. In 2000, after grad school, I took a job with Sports Illustrated. Two years later, I was assigned a feature story on the Spurs. When I showed up, Popovich referred to me as “the Pomona kid.” It would be the first, and only, time that my alma mater provided a reportorial advantage in the sports world. In the years that followed, Budenholzer steadily advanced within the Spurs organization as the team made trip after trip to the NBA Finals. Soon enough, he was promoted to lead assistant. Meanwhile, Levien left his job as an agent to become assistant GM of the Sacramento Kings in 2008. Three years later, when things didn’t work out in Sacramento, he joined an ownership group that purchased the Philadelphia 76ers. Last year, continuing his rapid ascent, he sold his stake in the 76ers to join the Grizzlies ownership group, along with an unlikely list of names that included Peyton Manning and Justin Timberlake. Majority owner Robert Pera, an old friend, named Levien the CEO and general manager.

So far, Jason says he’s enjoying the job. He keeps tabs on Budenholzer, whom he remembers as “the best competitor on the team” at Pomona, and still occasionally employs maxims he learned from Katsiaficas, including “be quick but don’t hurry.” “To me, Pop’s success made the NBA world seem more accessible and smaller,” he says of the Pomona connection. “And the time I spent on the team, I tried to learn as much as I could about the game. I really tried to suck it all in, because I knew Kat got much of his stuff from Pop.”

So far, Jason says he’s enjoying the job. He keeps tabs on Budenholzer, whom he remembers as “the best competitor on the team” at Pomona, and still occasionally employs maxims he learned from Katsiaficas, including “be quick but don’t hurry.” “To me, Pop’s success made the NBA world seem more accessible and smaller,” he says of the Pomona connection. “And the time I spent on the team, I tried to learn as much as I could about the game. I really tried to suck it all in, because I knew Kat got much of his stuff from Pop.”

As for Pop, well, he just kept on winning. Four NBA titles. A better winning percentage than any team in pro sports over the last 16 years. Another trip to the Finals last season behind Tim Duncan and Tony Parker. As time passed, he softened. A year and a half ago, when I wrote a feature story on Duncan, Popovich teared up while describing his star player. He told me about swimming in the Virgin Islands with Duncan when the two first met. He referred to him as close to a “soulmate.” He got equally gooey talking about Budenholzer, who he referred to as his “co-head coach.”

Mike? For many years, people around the league assumed he would succeed Pop when he finally retired in San Antonio. Every offseason, Budenholzer received inquiries from teams in need of a head coach. Every season he said no. Then, finally, after 19 years with Popovich, he accepted the head coaching job with the Atlanta Hawks this past May. His new boss was an old Spurs player, and front office figure, Danny Ferry. The timing, only days before the Spurs played the Heat in the NBA Finals, was rough. San Antonio went on to lose the series 4-3, in heartbreaking fashion. Mike had to go straight to work at his new job. This year, Budenholzer enters the NBA season with a rebuilt roster and midsize expectations. In Memphis, Levien presides over a team with a new coach and loftier goals. After advancing to the Western Conference Finals last season, and buoyed by a stellar defense, Memphis is well-positioned to make a run at a finals appearance. And the Spurs, as always, remain title contenders. Year by year, against the odds, the Pomona influence grows.

TWENTY YEARS’ TIME can color one’s memories, but certain truths remain. Recently, under the auspices of reporting this article, I convened with my old teammates Cover and Romney for beers at a rooftop bar in San Francisco. Cover was close to Budenholzer, and remains so. He talked about Mike’s competitive fire, about all the pickup games the two played together up and down the California coast, about that one beautiful scoop layup Mike hit against Redlands his senior year. For two weeks one summer, Mike slept on the Cover family couch. Afterward, Budenholzer sent Mrs. Cover a thank-you note. “What kind of college kid does that?” Cover asks, incredulous. Cover had his own brief pro basketball odyssey. After Pomona, he played for two years in Australia, the lone American import on a team. He now lives in Petaluma, with his wife and three daughters, managing a real estate business. He says he doesn’t play hoops anymore; it brings out the competitive beast inside.

Other teammates tell similar stories: Christiansen, who now works in finance, operations and human resources at Nike, gave up recreational basketball at age 38, but found his Pomona hoops experience has helped as “a badge of honor” and to “open doors,” and that it is also invaluable in corporate team-building. Romney, who is now at One Medical Group in San Francisco, played for the corporate team at Oracle, where he worked for a while, but hasn’t laced them up in a year. And Kelly, the lefty point guard, is a film/television agent in Los Angeles who’s retired from hoops, though not by choice. He tore both his Achilles.

Basketball careers done, they have all moved on. Life beckons, with all its playdates and late nights at the office and Saturday morning youth soccer matches. The game falls into relief, a treasured memory, a glimpse of a former self. The perspective changes. Now, when it comes to hoops, they live vicariously through Levien, Pop and Budenholzer.

The successes of those three become, in some way, communal successes. And so the game lives on.