On a summer day in 1922, as the strains of opera music and applause from the commencement audience faded away, President James Blaisdell presented a doctor of laws to Fong Foo Sec, the College’s first Chinese immigrant student. It was only the third LL.D awarded since the College’s founding 35 years earlier, and the story of a peasant laborer turned goodwill ambassador receiving an honorary degree attracted coverage from as far afield as the New York Times.

Fong had become the chief English editor of the Commercial Press, China’s first modern publisher. At Commencement, he was praised as an “heir by birth to the wisdom of an ancient and wonderful people; scholar as well of Western learning; holding all these combined riches in the services of a great heart; internationalist, educator, modest Christian gentleman.”

Fong had become the chief English editor of the Commercial Press, China’s first modern publisher. At Commencement, he was praised as an “heir by birth to the wisdom of an ancient and wonderful people; scholar as well of Western learning; holding all these combined riches in the services of a great heart; internationalist, educator, modest Christian gentleman.”

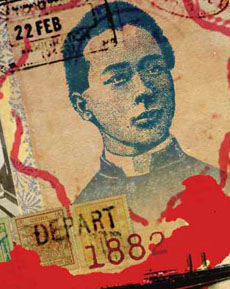

The pomp could not have been more different than Fong’s arrival four decades earlier, when his improbable journey to Pomona began under the cover of twilight. After his steamship docked in San Francisco in 1882, the scrawny 13-year-old boy hid in a baggage cart, while his fellow passengers banded together to fend off attackers along the waterfront, in case the immigrants were discovered before reaching the sanctuary of Chinatown.

“I was received with bricks and kicks,” Fong said, describing his reception in a magazine interview and in his memoirs decades later. “Some rude Americans, seeing Chinese laborers flock in and finding no way to stop them, threw street litter at us to vent their fury.”

Fong’s immigrant tale is both emblematic and exceptional: emblematic in the peasant roots, the struggles and dream of prosperity he shared with Chinese laborers of that era. Exceptional in the fact that Fong, though he came as a laborer, was able to get a college education in the U.S. and seize the opportunities it brought. He arrived at a time when formal immigration restrictions were scant, but also to a land gripped by anti-Chinese hysteria, just before a new law that, in the words of historian Erika Lee, “forever changed America’s relationship to immigration.”

IF FONG, IN HIS TINY VILLAGE in Guangdong province in southern China, had heard of such threats against his countrymen, he remained undeterred in his quest to go to Gold Mountain, a name California had picked up during the Gold Rush era. Fong’s childhood nicknames, Kuang Yaoxi, “to shine in the West” and Kuang Jingxi “to respect the West” are revealing. “He was expected, or perhaps destined, to become associated with the Western world and Western culture,” says Leung Yuen Sang, chairman of the History Department at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who has conducted research on Fong.

Born in 1869, Fong tended his family’s water buffalo and planted rice, taro and sweet potatoes, but did not begin school until he was 8. Often hungry, he went barefoot and wore patched clothes, reserving his shoes for festival days, Fong wrote in his memoirs. But his father saw a way out for Fong. From the start of the 19th century, his clansmen, driven by bandits, floods, war and rebellion, went abroad to seek their fortunes. After seeing villagers travel to America and return with “their pockets full,” his father asked Fong if he’d like to go too.

To pay for his ticket, the family borrowed money from relatives and friends, a common practice for would-be travelers. In January 1882, accompanied by his neighbor, Fong left for Hong Kong where he stayed before sailing for San Francisco on the S.S. China. In the crowded hold, amid stormy weather and high waves, he learned his first words of English and picked up advice. Fong’s steamship was one of scores jammed with thousands of his compatriots who began rushing over while the U.S. Congress debated a moratorium on most immigration from China.

According to his memoirs, Fong arrived sometime after the passage, on May 6, 1882, of what became known as the Exclusion Act, but before it took effect 90 days later. The San Francisco Chronicle published the arrivals and passenger load of steamships from the Orient, noting in March of that year, “It is a matter of some interest to know just how many Chinese are likely to be pressed upon our shores.”

The Chronicle also wrote of crowded, unclean conditions aboard steamers, which were anchored on quarantine grounds and fumigated to prevent the spread of smallpox. In headline after headline, the newspaper created the sense of a city besieged: “More Chinese: Another Thousand Arrive in This Port,” “And Still They Come … Two Thousand Others on the Way,” “Another Chinese Cargo: Eighty Thousand Heathen Awaiting Shipment to This City.”

ANTI-CHINESE SENTIMENT had been building for decades on the West Coast. During economic downturns, the immigrants, with their cheap labor, became scapegoats. Mob violence flared against them, and in San Francisco, in 1877, thousands of rioters attacked Chinese laundries and the wharves of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, the chief transpacific carriers of the laborers.

California had already passed its own anti-Chinese measures, and after years of pressure, particularly from the West Coast, Congress took unprecedented federal action in the form of 1882’s Exclusion Act. The 10-year ban on Chinese laborers would be the first federal moratorium barring immigration based upon race and class. Only merchants, teachers, students and their servants would be permitted to enter thereafter.

At first, confusion reigned. When the Exclusion Act took effect, a Chronicle headline proclaimed that the arrival of the “last cargo” of Chinese in San Francisco was “A Scene that Will Become Historical.” Still, the Chinese continued arriving as enforcement in the beginning remained haphazard. The act represented the U.S. government’s first attempts to process immigrants, and officials at the ports weren’t sure how to handle Chinese laborers under the new regulations, says Erika Lee, director of the Asian American Studies Program at the University of Minnesota. But in time the law succeeded in reducing Chinese immigration, which plummeted from 39,579 in 1882 to only 10 people, five years later. The Chinese population in the West shrank, as immigrants moved east to work and open small businesses. In the months and years to come, restrictions would tighten, with Chinese required to carry certificates of registration verifying legal entry. Later on, the right to re-enter the U.S. would be rescinded, and the act would be renewed.

“Beginning in 1882, the United States stopped being a nation of immigrants that welcomed foreigners without restrictions,” Lee argues in her book, At America’s Gates. “For the first time in its history, the United States began to exert federal control over immigrants at its gates and within its borders, thereby setting standards, by race, class, and gender for who was to be welcomed into this country.”

AFTER ARRIVING IN SAN FRANCISCO, Fong was forced to hide in a basement his first few days in Chinatown, a neighborhood of narrow alleys and cramped tenements, but also of temples and gaily-painted balconies. Laws targeting Chinese—their tight living quarters and their use of poles to carry loads on sidewalks— reflected the simmering resentment. “The city authorities, because they had not been able to prevent their coming, tried to make it difficult for [the Chinese] to settle down here,” Fong wrote.

Like many immigrants, Fong turned to kinsmen for help. He left for Sacramento to live with an uncle, a vegetable dealer, who found him a job as a cook to a wealthy family. He earned $1 a week, along with the occasional gift of a dime, which he treasured “as gold.” He—like many Chinese immigrants—sent money back to cover the debt incurred to cover his passage to America and pay for family expenses.

Like many immigrants, Fong turned to kinsmen for help. He left for Sacramento to live with an uncle, a vegetable dealer, who found him a job as a cook to a wealthy family. He earned $1 a week, along with the occasional gift of a dime, which he treasured “as gold.” He—like many Chinese immigrants—sent money back to cover the debt incurred to cover his passage to America and pay for family expenses.

At his uncle’s urging, Fong studied English at a night school set up by the Congregational Church in Sacramento’s Chinatown, but he started gambling and stopped going to class. Scolded by his uncle, he returned to school and a new teacher, Rev. Chin Toy, became his mentor.

Fong found himself debating whether to convert to Christianity. Among his parents, relatives, and friends, not a single one was Christian, and he hesitated giving up the idols his ancestors had worshipped for generations. “If Christianity turns out to be unreliable, I will lose heavily,” he wrote in his memoirs.

After a fire gutted the heart of Sacramento’s Chinatown and destroyed his few possessions, Fong had to move into a dark basement room, thick with his uncle’s opium smoke. Fong then asked if he could stay in the mission church, and Rev. Chin consented to the unprecedented request. From age 15 to 17, Fong lived in the mission, where he learned Chinese, the Bible, English, elementary science, and read books such as Pilgrim’s Progress and Travels in Africa. Six months later, he was baptized, but it took the Salvation Army to stoke his religious passion.

Drawn by the sound of the bugle one night, coming home from his cook’s job, Fong watched the preachers in the street, fervent despite a jeering crowd. Their zeal led him to question his faith and whether his sins had been forgiven. Struck by a vision of Christ’s breast streaming with blood, he knelt during a church service and repented.

His conversion was unusual—missionaries in those days did not make deep inroads among Chinese immigrants, who “did not seem to see the efficacy of a god who sacrificed his son on a cross,” says Madeline Hsu, director of the Center for Asian American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. “Until there was a better sense of community and utility in attending church, missionaries seemed largely ineffectual.”

The Salvation Army, unable to proselytize among the Chinese until Fong joined up, sent him to their San Francisco headquarters in 1889 for six months of training. As a preacher, Fong became the object of “laughter, bullying, and insults. As a Chinese, I suffered more than any Westerner,” he wrote. Still, for more than a year, Fong evangelized in California, Oregon and Washington.

One night, a brawny man in the street started beating Fong, who could not defend himself, and the teenager escaped after a woman intervened. Another time, while Fong passed a football field, boys swarmed around him, spitting and assaulting him until he found refuge in a nearby house.

After a labor meeting to discuss measures against the Chinese, boys began following Fong, who brandished a paper knife to ward them off. He might have found his greatest peril in Tacoma, Wash., where mobs in November 1885 drove out every Chinese, part of a wave of xenophobic violence sweeping the West. During an evening meeting sometime after the anti-Chinese riots, Fong’s friends heard voices outside and urged him to change out of his Salvation Army uniform, hide in a friend’s house and then aboard a ship anchored in the harbor where he spent the night. “Later, it came to light several hundred people had gathered outside the door of the meeting place, ready to seize me,” he wrote in his memoirs.

Fong endured. After taking typing and shorthand in night school, he became a clerk at the Salvation Army, and then was promoted to secretary to a major, the organization’s ranking leader on the Pacific Coast. The next few years had “significant bearing” on his future, he wrote, because he associated with people of “superior class” who spoke fluent English. On his own, he studied history, archeology and literature, and honed his public speaking and debate skills.

BUT FONG HAD AMBITIONS that would lead him to Pomona—and, eventually, back to China. “If I could obtain higher learning, I could go back and be of service to society,” he wrote in his memoirs.“To spend my whole life in a foreign country did not seem to me the most ideal solution.”

In 1897, Fong met Pasadena businessman Samuel Hahn, whose son, Edwin, attended Pomona. Fong shared his dreams with them. Edwin Hahn, in turn, told Cyrus Baldwin, Pomona’s first president. Not long after, President Baldwin called upon Fong in San Francisco at the Salvation Army headquarters, urging him to come at once. Fong’s $300 savings, and his pledge to work part-time, would cover his tuition, the president assured him. Years later, Fong would name his first-born son Baldwin in gratitude.

Fong entered Pomona’s prep school, cleaning houses, waiting on tables, typewriting, picking apples and cooking to cover his expenses. Like some students, Fong built a wood shack to save on rent and prepared his own meals, harvesting vegetables from a friend’s garden, according to classmate Charles L. Boynton, who contributed to a memorial volume after Fong’s death. Rev. Boynton would become a missionary in Shanghai. (With the College’s Congregationalist roots, a good number of Pomona students went on to become missionaries in the early days.)

Fong entered Pomona’s prep school, cleaning houses, waiting on tables, typewriting, picking apples and cooking to cover his expenses. Like some students, Fong built a wood shack to save on rent and prepared his own meals, harvesting vegetables from a friend’s garden, according to classmate Charles L. Boynton, who contributed to a memorial volume after Fong’s death. Rev. Boynton would become a missionary in Shanghai. (With the College’s Congregationalist roots, a good number of Pomona students went on to become missionaries in the early days.)

As a student, Fong helped bridge the gulf between cultures and countries, a role that would become his life’s work. He was seen as an expert on his homeland. Under the headline “The Views of a Bright Chinese Student,” the Los Angeles Times printed the transcript of a lengthy address Fong had given in Los Angeles regarding current events in China. And Boynton asked Fong—known as “Sec” or “Mr. Sec”—to speak with students planning to become missionaries in China, to share what he knew of the country and to make a personal appeal for evangelization. Fong also began his decades-long involvement with the YMCA during this time, after hearing about a fellow student’s account of young people surrendering their lives to Christ at a gathering on the hillside overlooking the ocean at sunset in Pacific Grove.

He interrupted his studies at Pomona twice: first, shortly after enrolling to accompany General William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, on a tour of the United States, and for a second time, in 1899, after he contracted tuberculosis and a physician ordered him to recuperate in a mountain camp for a year. “I was under the impression there was no cure for the disease and that it was a matter of a few months before my life, with its hopes crushed and work undone, would come to an end,” Fong later wrote in a letter.

A friend reasoned with him, helping restore his enthusiasm, and he looked fondly upon his time at Pomona. “Five years in college and all the assistance from friends—these I cannot forget.” After four years in Pomona’s prep school followed by a year of regular collegiate enrollment, he transferred to the University of California at Berkeley, where he graduated with honors with a bachelor of letters in 1905. He then headed east to Columbia, where he earned dual master’s degrees in English literature and education—fulfilling a prophecy. A generation ago, a fortune teller told Fong’s grandfather that an offspring would be awarded high academic honors.

FONG RETURNED TO CHINA in 1906 after a quarter-century absence. “The people are my people, and it doesn’t take long for me to forget that I had seen life—lived, struggled—in the West, and I was one of them once more,” he wrote.

He taught English and landed an appointment at the Ministry of Communications before taking his post at the Commercial Press in Shanghai, which published textbooks and translations. Such work contributed much to the educational development of China, which he considered vital to ensuring the country’s survival. Fong believed Chinese students also had to understand sciences, art, history, law and the government of Western countries.

In the decades ahead, Fong would become a prominent volunteer leader in Rotary International and the YMCA, and travel to Europe, Australia and the United States. And yet, despite his degrees, despite his accolades, under the Exclusion Act, he was not unlike the lowliest Chinese laborer who returned to his village after spending years in Gold Mountain.

America, it seemed, wasn’t ready for them. Permanent settlement in the U.S. was not an attractive option, because Chinese were prohibited from becoming naturalized citizens and faced a limited set of economic and social options. Many Chinese Americans were barred from certain professions, such as practicing law, even if they were college graduates. “It is notable that he ‘made his mark’ in China, not the U.S,” says Lee. During this time, the U.S. system for dealing with immigrants was becoming more and more formalized. Only a few years after Fong returned to China, an immigration station for detaining new and some returning Chinese immigrants opened on Angel Island in the middle of San Francisco Bay. By then, the Exclusion Act had set into motion new modes of immigration regulation that would give rise to U.S. passports, green cards, a trained force of government officials and interpreters, and a bureaucracy to enforce the law.

When Fong died in 1938, the Exclusion Act was still in effect. It wasn’t until five years later, when China and the United States became allies during World War II, that Congress repealed it. Large-scale Chinese immigration wasn’t allowed until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act two decades after the war’s end.

But throughout his life, Fong had remained optimistic about the power of education to alter American attitudes toward the Chinese, even if the laws hadn’t caught up to reflect that change. He exuded that spirit in an interview with a YMCA magazine, Association Men, in 1922, the same year he returned to the U.S. to receive his honorary degree from Pomona.

“The presence of several thousand Chinese students in your colleges and universities has given you a truer conception of us, than you get from the Chinese laundrymen,” Fong said. “The change which has come over the American is truly remarkable … you receive me with cordiality and friendliness. I am hailed as an equal.”