In those bleaker moments, with a player writhing on the field—again—it seems as if there’s no fixing football. The sheer force of the sport’s intrinsic and inextricable violence overwhelms one well-meaning new rule after another. There is some wringing of hands by authority figures—even the President, an ardent sports fan, expresses some grave concerns about the game and its costs—and a sense that Something Must Be Done, if notably less sense of what that might be. That was the state of football in 1906.

It’s the state of football in 2013, too. The same managed, choreographed violence that drives the game’s popularity can’t be managed or choreographed into un-violence. That reality, football’s defining conflict and central contradiction, would be recognizable to a fan from 1906. The game itself, though, would not be. Contemporary football’s intricate passing-driven offenses, as well as the speed, strength, skill and sheer tonnage of the players involved, make today’s game seem even more than a century removed from the version played around the turn of the 20th Century.

Take, for instance, the game played between Pomona and Stanford on Oct. 27, 1906, at Fiesta Park in Los Angeles. The players on those two teams averaged a little under 160 pounds. (If you were wondering: There is no player on this year’s Stanford roster who weighs less than 170 pounds, and a dozen listed at 298 pounds or more.) This wasn’t just a time in which Pomona College had a football rivalry with the 2012 Rose Bowl Champions, it was a time in which those two football teams were roughly equivalent in size and skill. But the strangest thing about that 1906 game was that these two teams of football players were squaring off in a game of rugby. How and why they were doing that is something of a long story, but it comes back to football’s old—and still contemporary—crisis of violence.

COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE EARLY part of the 20th century was, by and large, an East Coast pursuit. While Pomona and Occidental had rivalries with present-day Pac-12 powerhouses such as USC, Cal Berkeley and Stanford, those games and the teams playing them weren’t held in especially high regard nationally. But if California football was considered, in the words of a 1905 article in Outing Magazine, “slow and second class,” the game was no less violent west of the Rockies.

The game’s roughness was then, as it is now, both a part of the game’s appeal and its distinctive mythos. No less a fan than Theodore Roosevelt wrote, in an 1893 response to concerns about football violence in Harper’s, that, “the sports especially dear to a vigorous and manly nation are always those in which there is a certain slight element of risk. Every effort should be made to minimize this risk, but it is mere unmanly folly to do away with the sport because the risk exists.” But injuries and even deaths continued to occur on the field, and the sporting press of the period happily hyped the violence. The presence of bought-and-paid-for players on bigger and more ethically flexible teams—a problem big-time college football is still working on, actually—added to the appearance of chaos. A round of rule changes in 1905 legalized the forward pass, opening up the game and diminishing the importance of the dull, grunt-y, straight-ahead brutality that the football writer Caspar Whitney dubbed “the beef trust.” The changes also led to the creation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, the predecessor of the NCAA. On the East Coast, university presidents further responded to the rising tide of injuries and on-field deaths with a series of “debrutalization” measures designed to make the game safer.

Unsurprisingly, they didn’t quite work. “The season of ‘debrutalized’ football ended … with a record of eleven deaths and ninety-eight players more or less seriously injured,” The New York Times reported in November of 1907. This was only a slight reduction in casualties and no reduction at all in the number of fatalities, although the Times did note, hopefully, that “not a single serious injury has been sustained by Yale, Harvard or Princeton.” On the West Coast, at Cal and Stanford, university presidents were notably more proactive. They dumped football entirely for the 1906 season, and replaced it with rugby.

This was not necessarily a popular decision at the time. In June of 1907, Berkeley high school students (naturally) staged demonstrations against the imposition of what the newspapers of the time called “the English game.” But the shift to rugby was one that Pomona reluctantly made as well. They had to play against someone, after all.

THE GREAT RUGBY EXPERIMENT didn’t last long at Pomona. Pomona was shut out by Cal, and while the Sagehens did win a tune-up game against Pomona High School in early October—“The game was not a particularly brilliant one,” the Los Angeles Times sniffed—they didn’t fare nearly as well against collegiate competition. Pomona was shut out again, 26-0, by Stanford shortly after that win against the local high school. “Pomona made a game fight to the end, and came very close to being enti-tled to a score,” the Los Angeles Times reported, quite possibly sarcastically. The headline in the Times, three days after that game, read “Pomona Drops Rugby Games.”

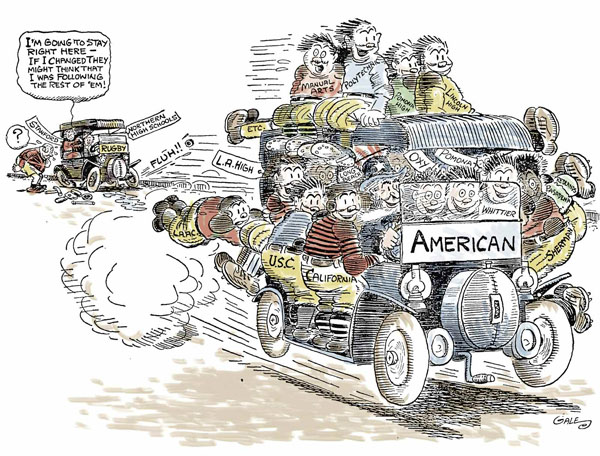

This was not the end of California’s football war. It was the end of intercollegiate rugby’s attempt at supplanting football at Pomona; the football team was back at practice by Halloween. It took Occidental and Whittier several years to follow suit, but within a few years a schism had emerged: Cal, Stanford and other Northern California schools played rugby, while by 1910, Pomona, Whittier and Occidental were playing football again, albeit against each other and teams from Colorado and Oregon instead of their larger and more geographically proximate rivals. “The two northern universities have adopted rugby for all time,” the Los Angeles Times columnist Owen Bird wrote in 1912. “The University of Southern California saw the way the tide was setting last year and took up the new game. Now it looks to be only a matter of time until the [Occidental] Tigers and the Sage Hens are forced to take up the game or lose standing with the athletic students of Southern California.

“This was not necessarily sportswriterly hyperbole on Bird’s part. “Rugby and American football are about on a par here,” Bird wrote, later in 1912. “This season will tell the tale as to which will survive.”

The answer, for a while, was both. Stanford, Cal and USC stuck with rugby, playing each other and teams from Canada and Australia for (very-far-) away games; the New Zealand All-Blacks, then as now one of the premier rugby sides in the world, swung through for an exhibition in 1913. But if rugby was an improvement on the brutal, dull, two-yards-and-a-cloud-of-ugh version of football that existed prior to the “debrutalization” rules and later reforms, the game that had emerged in the intervening years was a different thing—something slightly less bruising, a good deal more open, and notably more like the sport that’s currently the most popular in the United States by a wide margin. With the more pass-friendly and marginally less vicious game catching on in the rest of the nation—and booming in Southern California—the rugby schools were increasingly isolated. And then, in 1913, Pat Higgins initiated USC’s proud tradition of high-confidence, high-volume football coaches by injecting some trash-talk into the dispute.

“It will be remembered that Pat Higgins stated recently that he could get up a football team of rugby players, who could show the American players a few tricks at their own trade,” Bird wrote in the Times on Dec. 12, 1913. “Said speech caused a river of wild argument to be loosed upon our devoted heads.” Less metaphorically, it also led to a heavily-hyped exhibition American-style football game on Christmas Day, at Washington Park in Los Angeles. Higgins put together a team of elite rugby players from Cal, Stanford, Santa Clara and USC; coach Jack d’Aule built a team of his own, with Pomona (four players) and Whittier (five) represented heavily. “This squad of local intercollegiate men are fast, in condition, veterans of the game, and, best of all, are fired by a mighty impulse to defend the game they love,” Bird wrote. The opposing side, Bird noted, “[ran] to beef”—they outweighed the football players by 23 pounds per player, on average. They were, for the most part, the best rugby players in the United States.

It is, admittedly, something of a stretch to say that the resounding and lopsided 24-2 win that the team of smaller players from smaller schools rolled up that day saved college football in California. The game was not necessarily going anywhere; there is, for better or worse, something in the American psyche and populace that loves football. It was still several years before the rugby schools—Stanford was the last—dropped the sport in favor of football, although it’s safe to say that their programs have recovered from the blow. But while football still has a great many problems of its own to sort out, that Pomona-powered win a little over a century ago did at least ensure that rugby isn’t one of them.