“HAMBA MUTALIA. Haaaaa woyeee. Hamba mutalia.”

Young Humphrey walks into the center of the crowd before his traditional mud-covered home. The metal jingles on the leather strips on his wrist, making a bright snap in the air.

Surrounded by their voices, chanting softly and clapping, he leads the procession, draped in the skin and testicles of a bull sacrificed to mark this momentous change. They make a clearing for him. He stops silent before an elder, who carefully lifts off the skin. More than 100 of the boy’s family, friends and fellow villagers envelope him with whoops of joy and dance.

The next phase of his coming-of-age ceremony has begun.

The ground vibrates as they lift their hands to the sky and dance. “Hamba mutalia … Haaaaa woyeee…”

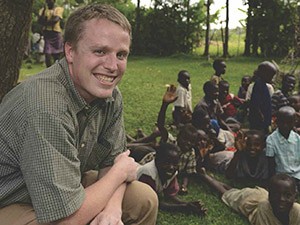

Michael Diercks, assistant professor of linguistics and cognitive science at Pomona, smiles, watching the circle of bodies sway and jump. In an instant, many people reach out and pull him into the fray.

They will celebrate throughout the night, encouraging 12-year-old Humphrey to have courage for morning, when he will go with them to the river to be covered in mud, and run home for the circumcision ritual to become a man.

It is one of the most important events in Bukusu life—a rite of passage that few outsiders ever see. Humphrey’s parents trusted Diercks to share the event, and want to preserve it for future generations.

“I feel like I know more about the world than I did 24 hours ago,” says Diercks in the morning. “We were experiencing something ancient, right in the present, through their rituals and dancing and singing, that are the same things they have been practicing for ages, perhaps even hundreds of years. It was as if we were transported back in time. When you looked up in the sky in the middle of the night, it could have been 100 years ago.”

Such intimate sharing and insight into Luhya language-speaking communities is the result of a multi-year collaborative international research project, of which Diercks is a principal investigator. A team of seven American linguists are studying four small Kenyan languages—Bukusu, Wanga, Llogoori and Tiriki.

The team is supported by several grants, including a prestigious $477,000 National Science Foundation grant. Much of Diercks’ work so far was made possible by the Hirsch Research Initiation Grant from Pomona College. The team includes Pomona Linguistics and Cognitive Science Chair and Professor Mary Paster and Pomona linguistics students, as well as researchers at Ohio State University, Southern Illinois University, the University of Maryland and the University of Missouri.

While there are more than 1.6 million speakers of the four Luhya languages, they are at risk, says Diercks, as everyday life changes to a less forested area and young people move toward English and Swahili for economic advantage. One example is the circumcision itself. More families are choosing hospital circumcision over the traditional way.

“As the community changes, so does the language, and what isn’t preserved may be lost,” says Diercks.

“As the community changes, so does the language, and what isn’t preserved may be lost,” says Diercks.

IN THE MOST comprehensive study of each of these languages to date, the team is collecting audio recordings from Luhya speakers and analyzing tone, sentence structure and other characteristics to describe how the language works. They are also collecting folk tales, narratives, songs and many other kinds of oral literature that document language use and aspects of each culture, as well as creating dictionaries for each language. Their research will be available in open-access venues for other scholars, and for Kenyans to learn about their languages.

“In the end, we are producing description and analysis of these languages that will be theoretically relevant and useful to furthering our knowledge of how human languages work,” says Diercks, “but also producing work that will be valuable to communities, whether for its role in preserving aspects of their language and culture, or in providing resources that will be useful in educational contexts, like adult and child literacy.”

So far, the team has collected and begun to analyze more than 100 hours of audio samples by Luhya speakers. Diercks, and phonologist and co-primary investigator Michael Marlo, from the University of Missouri English Department, have spent a lot of time in Kenya fostering the close-knit relationships needed to gain trust and access to different communities.

Diercks has been to Kenya many times. Earlier this year, he spent several months with a Tiriki family, gathering interviews and training Kenyan research assistants Kelvin Alulu and linguist Maurice Sifuna to collect interviews year-round.

Back in California, the students in Paster and Diercks’ Field Methods of Linguistics course are at the center of Luhya work.

“The field methods class is a great opportunity for students to apply their knowledge of linguistic theory to real languages, which are much messier and more interesting than the data sets they see in theory courses,” says Paster. “We try to find speakers of lesser-known languages so that students have an opportunity to break new ground and publish their findings. Our students this year are doing professional-quality research and writing that will be the basis for all of our future work on Llogoori.”

“I’ve been able to have so many experiences that I would not have had at another university,” says aspiring linguist Alex Samuels ’15. “Professors need research assistants. At other places, it would be graduate students doing the work I’m doing. Here, it gets to be me, which is awesome.”

As a Summer Undergraduate Research Program scholar, Samuels also spent the summer researching aspects of Llogoori with Paster. Since there is no published grammar of Llogoori, Samuels’ final paper from the previous semester is this fall’s required reading in the advanced fields methods class. “I was really proud,” he says.

WHAT LUHYA SPEAKERS choose to share is a mixed bag. Linet Kebeya Mmbone spoke about hardships after losing her husband, and raising her children as a single mother without skills. Mungambwe talked about Llogoori history. Retired police officer Benjamin Egadwe spoke about how men used to have several wives, and changes in community since Christianity arrived.

Ultimately, the stories will be shared with community members, along with images and stories generated by a volunteer photojournalist who spent several weeks in Kenya last summer. Together, they help to create an intimate portrait of the communities in which the linguistic team works; a snapshot of who they are and what’s important to them. Back at Pomona, the photographs and portraits are connections to the stories and texts students study, 9,500 miles away.

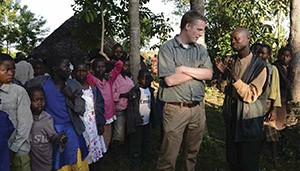

This summer, Diercks was able to see the pride Benjamin and other Llogoori speakers have in their culture and in the language project, when Alulu organized a celebration of progress so far.

They took motorbike taxis over windy dirt paths through the forest to their village. When they arrived, Mugangwe, Egadwe, and a dozen others ran out to meet them, dressed in their finest suits and traditional kanga cloths, and singing traditional greeting songs. They had walked hours into town for a goat, which they slaughtered for the feast.

“This was a big moment for me,” says Diercks. “We spend so much of our time  with individual people and then holed up analyzing the language, we don’t always get to see the whole community come together and celebrate research progress. It’s easy to focus on the academic side of things, but a celebration like this really drives home how intertwined language is with our identity, and how even small research advances matter so much to the community.”

with individual people and then holed up analyzing the language, we don’t always get to see the whole community come together and celebrate research progress. It’s easy to focus on the academic side of things, but a celebration like this really drives home how intertwined language is with our identity, and how even small research advances matter so much to the community.”

At the celebration, Diercks also got a taste of what the project means to the Luhya speakers who have the opportunity to share. “This is how we teach our current children about how the Llogoori used to live,” says Egadwe. “Children have new customs. We feel it is good to teach them this way. Most of the old people do not remain. We are now the old people, telling our ways. This is a way to preserve our culture. We are taking good care of it.”

THE WORDS THAT galvanized a thousand authors to speak out against a powerful corporate retailer were written along a dirt road, in an 8-by-10 shack, by a wispy-haired, self-described “wimp.”

THE WORDS THAT galvanized a thousand authors to speak out against a powerful corporate retailer were written along a dirt road, in an 8-by-10 shack, by a wispy-haired, self-described “wimp.”

ney, Aaron Becker ’96 offers the second installment in an intended trilogy of brightly colored fantasy adventures without words.

ney, Aaron Becker ’96 offers the second installment in an intended trilogy of brightly colored fantasy adventures without words. Joan Benson ’46, a champion of the clavichord in the modern world, offers a method book for practitioners and enthusiasts alike, including a master class DVD and a CD of Benson performing.

Joan Benson ’46, a champion of the clavichord in the modern world, offers a method book for practitioners and enthusiasts alike, including a master class DVD and a CD of Benson performing. Reanne Hemingway-Douglass ’63 tells the little-known World War II story of an escape route that the French Resistance used to rescue Allied airmen shot down over France.

Reanne Hemingway-Douglass ’63 tells the little-known World War II story of an escape route that the French Resistance used to rescue Allied airmen shot down over France.

clash between an old family legacy, tribal land rights, and a marriage in trouble results in a suspicious death, threatening the lives of those who try to solve it.

clash between an old family legacy, tribal land rights, and a marriage in trouble results in a suspicious death, threatening the lives of those who try to solve it.

A National Book Award finalist, Professor of English Claudia Rankine’s meditation on race recounts the racial aggressions of daily life in America in a progression of revealing vignettes.

A National Book Award finalist, Professor of English Claudia Rankine’s meditation on race recounts the racial aggressions of daily life in America in a progression of revealing vignettes.

DURING VISITS TO her hometown of Baltimore while she was a student at Pomona, Celia Neustadt ’12 started to notice some interesting shifts in the makeup of the city’s public spaces. The Inner Harbor waterfront, long seen by locals as a tourist-only enclave, had started attracting black teens from around the city looking for a place to shop and meet friends, a big change from when Neustadt herself was a Baltimore City high school student.

DURING VISITS TO her hometown of Baltimore while she was a student at Pomona, Celia Neustadt ’12 started to notice some interesting shifts in the makeup of the city’s public spaces. The Inner Harbor waterfront, long seen by locals as a tourist-only enclave, had started attracting black teens from around the city looking for a place to shop and meet friends, a big change from when Neustadt herself was a Baltimore City high school student.

These are the words I used four years ago to explain why we were then launching a five-year campaign to raise $250 million in support of some very ambitious goals. My point is the same now as it was then: This isn’t just about Pomona. It’s about the future. And it’s about all of us.

These are the words I used four years ago to explain why we were then launching a five-year campaign to raise $250 million in support of some very ambitious goals. My point is the same now as it was then: This isn’t just about Pomona. It’s about the future. And it’s about all of us. wn online store that sells unique vintage clothes. First created while he was a student at Pomona, Jonathan’s brand, STARZYK, is now based out of his hometown of Chicago. There, he’s working to make the business take root in the city and continue its growth, using creative efforts to connect with local buyers while still reaching style-minded guys across the country.

wn online store that sells unique vintage clothes. First created while he was a student at Pomona, Jonathan’s brand, STARZYK, is now based out of his hometown of Chicago. There, he’s working to make the business take root in the city and continue its growth, using creative efforts to connect with local buyers while still reaching style-minded guys across the country.

After a near 50-year hiatus from contact with the College, I am now re-engaged. Two obvious factors have been the 50th–Year Reunion and the College’s email listserv. A third factor is your excellent publication. Very professional in layout and content. I suspect this may play a role in the increasing recognition of the College in national publications.

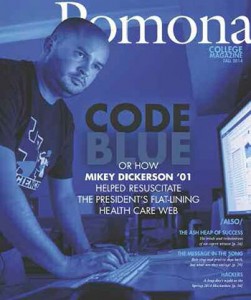

After a near 50-year hiatus from contact with the College, I am now re-engaged. Two obvious factors have been the 50th–Year Reunion and the College’s email listserv. A third factor is your excellent publication. Very professional in layout and content. I suspect this may play a role in the increasing recognition of the College in national publications. Commentary on PCM, Fall 2014: For some of us, coding is a means to an end, not an end in itself. It has to be continually upgraded. A while ago, I wrote a large number of papers on wavelets, but only as long as I had access to MATLAB’s Wavelet Toolbox.

Commentary on PCM, Fall 2014: For some of us, coding is a means to an end, not an end in itself. It has to be continually upgraded. A while ago, I wrote a large number of papers on wavelets, but only as long as I had access to MATLAB’s Wavelet Toolbox. I have wanted to write this letter for some years, but your August 29 letter, along with the current issue of Pomona College Magazine, prompted me to write you immediately.

I have wanted to write this letter for some years, but your August 29 letter, along with the current issue of Pomona College Magazine, prompted me to write you immediately. Sagehen Senate

Sagehen Senate