Hilary Swarts ’94 on the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge

Photos By Crystal Kelly

SURVIVAL CAN BE A REAL CAT FIGHT when you get squeezed out of your rightful home. When your food supply dwindles. When you are small and cute and easy to run down. Even though you are standoffish and try to keep to yourself.

In 22 countries, from Uruguay to south Texas, the ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), one of smallest and most secretive of all wild cat species, is facing this sad plight. Its habitat—thorn scrub, coastal marshes, tropical and pine-oak forests—has shrunk alarmingly, swaths destroyed by building and farming and other human activity. With diminished space in which to establish territories, find secure denning sites and forage for rodents, birds, snakes, lizards and other prey—plus the increased threat of becoming road kill as highway construction boomed in the 20th century—the ocelot has been in the fight of its life.

Back in the 1960s and early ’70s, ocelots were nearly loved to death. Laws then did not prohibit taking them for exotic pets or hunting them for their beautiful, dramatically marked fur. Babou, Salvador Dali’s frequent sidekick, may have been the most famous of captive ocelots.

In the U.S., as the wild population of these little cats became depleted under development pressures, the fashion industry turned to import, reaching a peak of 140,000 pelts from Central and South American countries in 1970. Toward the end of the century, all these human endeavors had chipped away at the historic U.S. ocelot range—which once stretched from Louisiana to Arizona—cornering the few known remaining individuals in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, where Texas meets the Mexican border and the Gulf of Mexico. Wildlife biologists, scientists, researchers, conservationists and other experts started running the numbers and saw that time was running out. Now, even after several decades of legal protection and some active conservation projects, only 55 or so known individual ocelots remain in the U.S.

Swarts with one of several “Ocelot Crossing” signs on the refuge

There are few rays of sunshine in this grim picture, but one of the brightest landed at Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge a little over three years ago in the form of wildlife biologist Hilary Swarts ’94.

Radio-collars are attached with breakable string. This one was dropped by a male bobcat.

CHARMED BY THE PROMISE of year-round Southern California sunshine, Swarts arrived at Pomona in 1990 from the four seasons of Greenwich, Conn., expecting college to be “a safe way to have an adventure.” She had no idea what that adventure would be or where it might lead, but she knew one thing for sure: “I always liked animals like crazy,” she says. “But it was two professors at Pomona who gave me the idea that you could have this kind of career—that jobs [with animals] other than veterinarian or zookeeper were possible.”

Swarts listens to the signal from a radio-collar.

It was in Anthropology Professor James McKenna’s courses on biological anthropology and primate behavior that she first encountered the area of study that would become her path into the world. “Animal behavior!” she says, “I was hooked.”

Another mentor, Biology Professor Rachel Levin, introduced her to the kind of research that would become her life’s work. Assisting Levin in her study of songbirds—including an eventual trip to Panama to study the communication behaviors of bay wrens in their natural habitat—fed Swarts’ enthusiasm and left her convinced that she was on the right track. And at a time when men still dominated the sciences, Levin also gave her confidence that she could succeed. “She showed me how women scientists work,” Swarts recalls. “I got amazing support from her.”

In her senior year, Swarts threw herself straight into fieldwork, flying to Tanzania to spend her study-abroad semester in a wildlife conservation program there. However, midway through the semester, her plan to be immersed in chimpanzee communities took a bad turn: “I broke my ankle, had surgery in Nairobi [Kenya] and spent four weeks at Lake Manyara National Park designing exhibits for the Arusha Natural History Museum.” Instead of taking a planned hike up Mt. Kilimanjaro, she hobbled around on crutches for the rest of her stay.

Despite these disappointments, she returned to Pomona and forged ahead. Since the College had no major in animal behavior, Swarts designed her own, combining the fields of her mentors to create a major in “biological anthropology.”

After graduation, she spent seven years project-hopping—from black howler monkeys in Belize to the famous mountain gorillas in Rwanda’s Parc National des Volcans. “Each work experience was confirmation that I’m doing the right thing,” she says. “I’d see something shiny and think, ‘That’s worth checking out.’ I’ve stumbled into some pretty amazing situations.”

If she had to pick a favorite, she says, it would be the time she spent in Suriname, monitoring a troop of capuchin and squirrel monkeys. “I lived in a hut with no electricity. The wildlife was mind-blowing. You’d stand still for five minutes, and all around you would come alive. Life was work and reading books and planning what to have for dinner and socializing with the locals.” She built up her explorer skill set by wielding a machete to cut trails and map sections of unexplored rain forest.

But eventually, despite all the “cool stuff” she was doing, Swarts began to wonder if she was missing the bigger picture. As an undergraduate, she had felt certain about two things: “I would not go to graduate school, and I would never work for the government.” Now, however, those vows were beginning to feel limiting. “I missed education and being surrounded by people who are curious and informed. I was ready to get into more academics.”

Entering the ecology program at the University of California, Davis, she earned a Ph.D. in ecology with an emphasis on conservation. Then, shrugging off that “never working for the government” notion, she took a job with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, working on regulatory projects involving endangered species. “Regulatory work is so important,” she emphasizes. But after a while, the day-to-day responsibilities of what she terms “desk biology” began to wear. “It’s soul-crushing work,” she explains. “You know exactly what each day, a month ahead, will be.”

So, when a job opening in the wilds of south Texas popped up in her email for a wildlife biologist charged with leading the hands-on effort to save the ocelot in the U.S., she leapt at the challenge.

THE LAGUNA ATASCOSA National Wildlife Refuge is a flat, sunbaked remnant of coastal prairie mixed with thorn bush, bordering on a vast hypersaline lagoon across from South Padre Island. Its dense thicket of low scrub is home to—at last count—15 of the remaining ocelots still living in the U.S., and for Swarts, it’s where the fight to save them from extinction is being waged.

Meeting with her here can feel like a bracing seminar in All Things Ocelot. For starters, she’ll whip her refuge pickup into her driveway (on Ocelot Road, of course) and say, pointing at the license plate on her 2000 Buick LeSabre, “Look!” The plate says “OCELOT” (of course), and the vanity fee collected by the State of Texas goes to Friends of Laguna Atascosa for outreach programs.

More important, it quickly becomes clear that she’s a walking compendium of information about the species she’s working to rescue. “We think that these Texas ocelots may have developed great fidelity to thick underbrush because of pursuit by hunters back in the 1960s,” she explains. More facts come tumbling out: Two-thirds of births are single, after a gestation of 79 to 82 days. Kittens stay with their mothers, to learn survival and hunting skills, for up to two years. “Although,” she adds, “I’m beginning to think it may be closer to a year and a half, if the teaching goes well and there is a reliable prey base. And the past two winters have been super wet, so there’s been prey out the wazoo.”

Swarts visits a wildlife underpass under construction. Though currently flooded, it will be dry when complete.

The first confirmed ocelot kitten at the refuge in 20 years.

(U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service photo)

Swarts holds a sedated ocelot, who was then given a radio collar and released. (U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service photo)

Working with ocelots, because they stay so well hidden, is different from her previous fieldwork, when she could watch the animals she was studying in their own environment (such as following gorillas around as they nosed about on their daily routines, which she describes as “total soap opera”). In fact, the only time Swarts and her small staff of interns actually see ocelots in the flesh is during trapping season, from October to May, when the little cats are lured by caged pigeons posing as an easy meal, then sedated long enough for blood and genetic samples to be taken. After a quick exam and insertion of a microchip, they are photographed, fitted with a GPS collar, given reversal drugs and released.

“With the ocelots, I’m essentially doing detective work,” she explains. Across the refuge, there are more than 50 cameras tucked into the thorn scrub, monitoring animal activity night and day. Using cameras and GPS collars may not be as immediately satisfying as shadowing gorillas, but it’s the only way she can keep tabs on the elusive little creatures she’s trying to save.

For instance, last year, on March 25, 2016, a heavily pregnant female was captured for routine data collection and then released. On the following two days, GPS signals from her collar indicated that she was staying put, likely in a den. After a few weeks, GPS showed more activity—she was almost certainly leaving the den for water, repeat behavior that is usual for a lactating female. “On April 15, when we knew she was away and couldn’t detect us, we found the little kitten, tucked under some Spartina. A male, healthy, weighing less than a pound, with his eyes just opened.” Swarts, who took hair samples, DNA swabs and his baby picture (below), was ecstatic to document and report this first confirmed ocelot den at the refuge in 20 years.

“From my perspective they are doing their job—reproducing,” she says. “And ecologically we are in great shape.” However, she has grave concerns that the confirmed refuge population of 15, including kittens, may be approaching capacity. Home range for a female varies from one to nine square miles, depending on the availability of water and prey. For a male, figure four to 25 square miles.

That brings us to exhibit one for the three top threats to survival of the species—habitat loss. Hemmed in by agriculture, highways and industry, the refuge itself can’t be greatly expanded. The other Texas ocelots, about 40 individuals, live on limited private lands in neighboring Willacy County, with no safe passage connecting the populations.

And that leads directly to the second threat—vehicular mortality, which stands at an astounding 40 percent. Swarts cites the ugly statistics that piled up between June 2015 and April 2016, when seven ocelots, including six males, were killed by vehicles on roads adjacent to fragile ocelot territory.

Which brings us to the third item on Swarts’ list of top threats to the ocelot’s long-term survival: in-breeding, which occurs when populations are so isolated that no new genes can get into the mix. Even before her arrival in Texas, efforts to freshen the gene pool by bringing in a female ocelot from Tamaulipas, Mexico, had started and stopped several times, partly due to cartel violence. Still, she remains optimistic that, with research and negotiation, a female from Mexico will eventually be allowed to cross the border.

Progress is agonizingly slow—as Swarts stoically puts it, “Conservation is often two steps forward and one step back.” However, she has begun to see encouraging signs. The refuge has cranked up an aggressive habitat restoration project—planting ocelot corridors, extensions of the habitat that ocelots are known to use, with the low-growing, bushy native species they prefer. As a precaution against vehicular mortality, the refuge has closed some of its roads and plans to relocate its entrance. Most heartening, the Texas Department of Transportation is installing 12 new underpasses specifically designed for ocelots at known hot spots on two highways where there have been multiple incidents of road kill. “And now it seems likely they will put wildlife crossings into new road design from the start,” she adds. “This is a sea change—and for this state agency to come around bodes so well for the state and its environmental future.”

The work is hard, sometimes tricky and frequently thankless. However, it also has its rewards. “I love the element of variety in my job,” she says. “The nuts and bolts. Speaking the legalese. Ocelot outreach. Hearing people’s questions. I get fired up; they get fired up.”

Best of all, there are the little discoveries, the aha moments that move her work forward. That den discovered in April? “It was a surprise to find it in an open area, not in super dense brush,” she explains. It’s new ocelot information, the kind that can drive new policy and practice. In this case, it may lead to a new prescribed burn protocol designed to leave a protective margin outside the brush.

For Swarts, as always, it’s about rethinking the ongoing help this little cat needs, using clues from her ongoing research, then doing whatever it takes. “I want to do everything I can to give these cats the best chance to survive.”

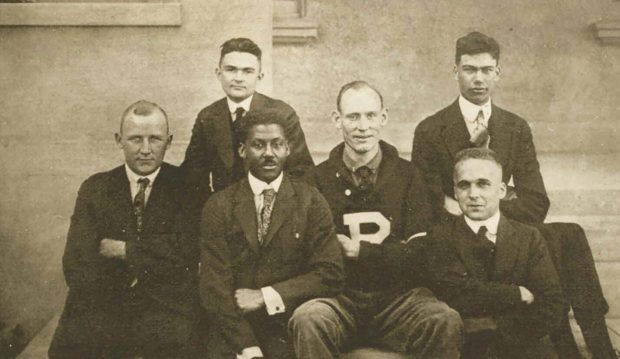

Desai: “… By now, we can accept as historical fact that the Japanese internment happened in the United States, and most people agree that it’s one of the darkest periods in American history. But the root causes of why the government so explicitly targeted Japanese Americans can be hard to parse out, so we talked to Pomona History Professor Samuel Yamashita. He said that the causes of the internment can be traced back to four distinct historical contexts, starting with the advance of European and American imperialism in the 19th century.”

Desai: “… By now, we can accept as historical fact that the Japanese internment happened in the United States, and most people agree that it’s one of the darkest periods in American history. But the root causes of why the government so explicitly targeted Japanese Americans can be hard to parse out, so we talked to Pomona History Professor Samuel Yamashita. He said that the causes of the internment can be traced back to four distinct historical contexts, starting with the advance of European and American imperialism in the 19th century.”

The play, written by Valdez, is based on the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial and the Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in early 1940s Los Angeles. The play tells the story of Henry Reyna and the 38th Street gang, who were tried and found guilty of murder, and their subsequent journey to freedom.

The play, written by Valdez, is based on the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial and the Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in early 1940s Los Angeles. The play tells the story of Henry Reyna and the 38th Street gang, who were tried and found guilty of murder, and their subsequent journey to freedom.

1. Huns to Hens

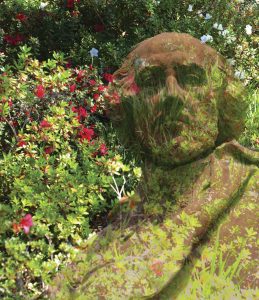

1. Huns to Hens 2. The Shakespeare Garden

2. The Shakespeare Garden 3. Things That Go Bump

3. Things That Go Bump 4. The Flying Sailboat

4. The Flying Sailboat 5. The Duke and the Madonna

5. The Duke and the Madonna 6. The Borg and the Borg

6. The Borg and the Borg

8. The Roosevelt Shovel and Oak

8. The Roosevelt Shovel and Oak 9. All Numbers Equal 47

9. All Numbers Equal 47 I received my Pomona College Magazine yesterday, opened it this morning to the last page and came unglued to see Virginia Crosby’s beautiful smiling face.

I received my Pomona College Magazine yesterday, opened it this morning to the last page and came unglued to see Virginia Crosby’s beautiful smiling face. “The Cane Mystery” article in the PCM summer 2016 issue was interesting and reminded me of the cane which I now have. The cane belonged to my father, Robert Boynton Dozier (1902–2001), Class of ’23.

“The Cane Mystery” article in the PCM summer 2016 issue was interesting and reminded me of the cane which I now have. The cane belonged to my father, Robert Boynton Dozier (1902–2001), Class of ’23.