Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold.

Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold.

Some of the answers surprised even Beck.

What’s Next For:

Revolutions?

Syria?

Mexico?

Japan?

The United States?

Earthquake Safety?

Climate Action?

California Water?

Climate Science?

Solar Energy?

California Fruit Farming?

Technology Investing?

Nanoscience?

Digital Storage?

Artificial Intelligence?

Cyber-Threats?

Social Media?

Space Exploration?

Science Museums?

The Sagehen?

Biodiversity?

The Blind?

Big Data?

Mental Illness?

Health Care Apps?

Maternity Care?

Etiquette?

Ballroom Dance?

Thrill Seekers?

Outdoor Recreation?

Funerals?

Writers?

Movies?

Manga?

Alt Rock?

Women in Mathematics?

The first to hazard a guess was George Lawson of the London School of Economics, who settled, provocatively, on a country that seems like the height of iron-fisted control—China. “China has more collective action events, more protests, than any other society in the world on a yearly basis,” Beck explains. “Most of them are local, anti-corruption protests against local corrupt elites. But George made a really good point—that one of the more robust findings in revolutions research is that, to the extent that a regime becomes personalized, as it becomes invested in a single individual as an expression of power, it also becomes more vulnerable, because it creates a target for people to impose their grievances on. So as Xi Jinping moves toward a much more personalist rule and away from the Politburo, away from the bureaucracy, that creates a potential danger in the years to come.”

Second up, Daniel Ritter of Stockholm University shifted the focus to the oil-rich kingdom of Saudi Arabia. “Another consistent finding in revolutions research is that revolutions are often catch-up events,” Beck says. “They’re taking societies that have not kept up with modernity and thrusting them into it. So as Saudi Arabia is trying to modernize its government and liberalize somewhat its society, they may actually be fueling the potential for mass protest.”

A third scholar, Sharon Erickson Nepstad of the University of New Mexico, refused to speculate about the next revolution. Instead, she made a suggestion about where it won’t be—the protest-torn state of Venezuela. “Because everyone would think that would be the place, right?” Beck says. “She’s done a lot of work on peace movements and the like, and she looks at the situation in Venezuela and thinks the opposition there hasn’t done the hard work of mobilizing that a successful movement needs to do. They haven’t built the organizational infrastructure. It’s not deeply rooted enough in society.”

Beck himself isn’t so sure, however. “The Venezuelan government shoots people dead in the streets,” he notes, “and shooting people dead in the streets is generally a losing strategy. I mean, it’s a successful short-term strategy but a poor long-term strategy—unless you shoot a lot of people down in the streets. Then it works, as terrible as that sounds.”

And what was Beck’s pick for the next revolution? “I decided that I would, provocatively, say what the political scientists are starting to call ‘the illiberal democracies’—Hungary, Turkey, Poland, Russia,” he says. “Turkey, in particular, is really setting itself up for a challenge. There’s a lot of concern right now about the illiberal democracies, and maybe this is the way of the future, but I think human rights, democracy—they’re too widely legitimated. They’re too embedded in normative consciousness globally for them to erode that quickly. Which means that these countries are going against the grain, and they’re creating the contradictions that can fuel future protest.”

There were two points, however, upon which all four scholars agreed.

First, most revolutions are likely to follow the same nonviolent path as the Arab Spring—unarmed civil protests as opposed to violent insurgencies—at least for now. “There’s definitely been this shift from the kind of mid-20th-century communist guerilla warfare model towards this kind of Berlin Wall-Arab Spring model,” Beck says. He wonders, however, how long that will last, given the fact that so many recent examples have ended in failure.

Their second point of agreement was surprising, given the usual narrative about the Arab Spring. “My colleagues and I all pretty much agreed that the effect of social media on revolutions has been overstated,” he says. “The thing I like to think about is that the biggest day of protests in Egypt happened the day after the Mubarak regime shut off the Internet. And the reason that was the biggest day of protests was because the Muslim Brotherhood decided to turn out, and the Muslim Brotherhood has a traditional form of grassroots organization.”

All of these speculations were intended to be a kind of engaging thought experiment, Beck says, adding the disclaimer that predictions of this sort are really little more than educated guesswork. He points to recent events in Armenia, where protests unexpectedly brought about a sudden change of leadership. “A few weeks ago, George wrote all of us to note that no one had mentioned Armenia at all,” he says. “It’s too soon to say what will happen there, but we saw the model again—protest and elite negotiation to force a change in who is in power. And none of us saw it coming.”

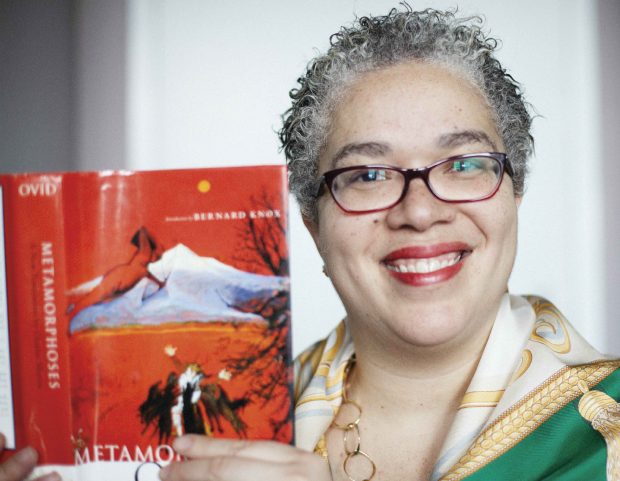

Murder at the Vicarage (and other Miss Marple mysteries) by Agatha Christie—“A childhood collection of Miss Marple novels was my first glimpse into reading as searching for signs—those hidden traces of human feeling, motive and mind.”

Murder at the Vicarage (and other Miss Marple mysteries) by Agatha Christie—“A childhood collection of Miss Marple novels was my first glimpse into reading as searching for signs—those hidden traces of human feeling, motive and mind.” Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen—“Jane Austen was a friend who got me through the awkwardness of being a smart child.”

Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen—“Jane Austen was a friend who got me through the awkwardness of being a smart child.” Clarissa, by Samuel Richardson—“Clarissa is not just about obsession, but it produces obsessive reading. It drew me into the 18th century with its psychological complexity and depth.”

Clarissa, by Samuel Richardson—“Clarissa is not just about obsession, but it produces obsessive reading. It drew me into the 18th century with its psychological complexity and depth.” The English Poems of George Herbert—“Herbert’s poetry has been part of my life—I fell in love with it in my second year of grad school, and I read his poems to my father as I sat beside him in his last hours.”

The English Poems of George Herbert—“Herbert’s poetry has been part of my life—I fell in love with it in my second year of grad school, and I read his poems to my father as I sat beside him in his last hours.” Cane, by Jean Toomer—“Cane is sheer beauty to me. The pages are heavy with it.”

Cane, by Jean Toomer—“Cane is sheer beauty to me. The pages are heavy with it.” The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien—“I took The Lord of the Rings when I was having both children. It’s on every device I own, even though I don’t know by heart half of it half as well as I would like.”

The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien—“I took The Lord of the Rings when I was having both children. It’s on every device I own, even though I don’t know by heart half of it half as well as I would like.”

Desai: “… By the time that some of the early founders of Pomona College arrived in Claremont, much of the Tongva population had been decimated by a major smallpox outbreak in 1862, a generation before the College’s founding. After the outbreak, the population of the Tongva in the area fell to around 4,000, a fraction of what it once was. When the founders of the College actually came to Claremont, there was barely a trace of the original people.”

Desai: “… By the time that some of the early founders of Pomona College arrived in Claremont, much of the Tongva population had been decimated by a major smallpox outbreak in 1862, a generation before the College’s founding. After the outbreak, the population of the Tongva in the area fell to around 4,000, a fraction of what it once was. When the founders of the College actually came to Claremont, there was barely a trace of the original people.”

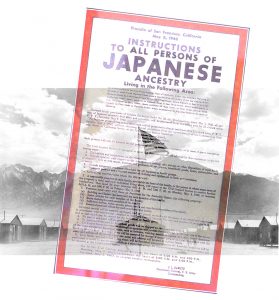

Desai: “… By now, we can accept as historical fact that the Japanese internment happened in the United States, and most people agree that it’s one of the darkest periods in American history. But the root causes of why the government so explicitly targeted Japanese Americans can be hard to parse out, so we talked to Pomona History Professor Samuel Yamashita. He said that the causes of the internment can be traced back to four distinct historical contexts, starting with the advance of European and American imperialism in the 19th century.”

Desai: “… By now, we can accept as historical fact that the Japanese internment happened in the United States, and most people agree that it’s one of the darkest periods in American history. But the root causes of why the government so explicitly targeted Japanese Americans can be hard to parse out, so we talked to Pomona History Professor Samuel Yamashita. He said that the causes of the internment can be traced back to four distinct historical contexts, starting with the advance of European and American imperialism in the 19th century.”