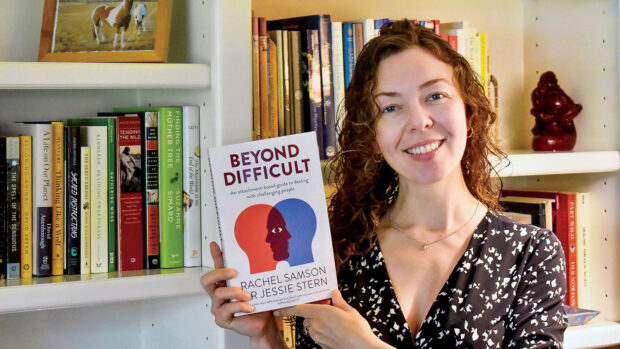

Last summer Assistant Professor of Psychological Science Jessica Stern ’12 published Beyond Difficult: An attachment-based guide to dealing with challenging people. An expert in attachment theory, close relationships and child development, Stern spoke with PCM about how she hopes the book will help readers.

Last summer Assistant Professor of Psychological Science Jessica Stern ’12 published Beyond Difficult: An attachment-based guide to dealing with challenging people. An expert in attachment theory, close relationships and child development, Stern spoke with PCM about how she hopes the book will help readers.

Who is this book for?

It’s for anybody who has had a difficult relationship—whether that’s in your family life, dealing with a difficult kid as an educator or as a parent, or navigating difficult work relationships. Most [of us] have had at least one relationship where we wished we had a guide we could pull out and say, “What do I do?” We wanted the book to be accessible, even to people who had never read a research paper before. We wanted them to know that there’s a fascinating science of how to build stronger marriages, friendships and workplace relationships.

You spend a lot of time focusing on highly sensitive and neurodivergent people. Why do you highlight these two groups?

These groups are often misunderstood and mislabeled, either as a bad kid or as a difficult adult. Everybody’s nervous system is wired a little bit differently [and] is not something we can change. But what we can do is provide a supportive environment that doesn’t overstimulate these kids so that they either act out or shut down. The same principle is true for adults—understanding that the person next to you might be more reactive to the context that they happen to be, we might look at the environmental circumstances that [lead] them to act in this way.

We also look at people’s relationship histories and attachment style. One major reason behind difficult behavior is that someone is feeling threatened, insecure or triggered. Usually that comes from a place of not having had secure, safe relationships as a child or as an adult. One nice thing about that framework is, first, it inspires a little bit more compassion, rather than combativeness, toward the person. But second, there are certain strategies that we can then use to help the relationship feel safe enough that the person can calm down and have a constructive conversation.

Secure vs. Insecure Attachment Styles

- Secure Attachment: Comfortable with intimacy and independence. Trusts partners.

- Anxious Attachment: craves closeness but fears abandonment, may appear clingy

- Avoidant Attachment: Values independence over intimacy. May appear distant.

- Disorganized Attachment: Desires connection but fears it. Sends mixed signals.

How did you and your co-author team up for this book?

Rachel [Samson] is a clinical psychologist in Australia. She and I met at a professional training many years ago and discovered that we had similar interests, but I was doing more of the scientific work and she was putting those ideas into practice with clients. It’s very easy for me, as a researcher, to say, “Here’s what people should do” in theory, but it’s a very different thing to be a practitioner who’s seen it in action with real people.

The book is divided into three parts. The first part is about understanding difficult behavior: getting a better grasp of what’s really going on when someone rubs you the wrong way. The second part is about working on oneself. Based on your own temperament and attachment style, what are the things that you’re bringing to this interaction that you can strengthen or improve? Part three is about the relationship. How do you strengthen it? What are specific things that you can do, like giving feedback in an effective way, not letting things stew? And what do you do when another person is just not going to change?

In his debut YA novel, Andrew Extein ’07 tells the angsty story of a bullied straight teenage boy who comes out as an act of retribution.

In his debut YA novel, Andrew Extein ’07 tells the angsty story of a bullied straight teenage boy who comes out as an act of retribution. This sci-fi crime novel by Greg Hickey ’08 follows a private detective hired by a space tech CEO to investigate a rival for illegal hydrocarbon combustion.

This sci-fi crime novel by Greg Hickey ’08 follows a private detective hired by a space tech CEO to investigate a rival for illegal hydrocarbon combustion. The fourth book of poems by Garrett Hongo ’73 draws inspiration from Hongo’s life journey and weaves in memories of various shorelines.

The fourth book of poems by Garrett Hongo ’73 draws inspiration from Hongo’s life journey and weaves in memories of various shorelines. This collection of Prof. Jonathan Lethem’s short stories spans 35 years of writing, serving as a career survey and retrospective.

This collection of Prof. Jonathan Lethem’s short stories spans 35 years of writing, serving as a career survey and retrospective. Nancy Matsumoto ’80 reports on women who are building local and regional supply chains, offering the reader a blueprint for eating sustainably.

Nancy Matsumoto ’80 reports on women who are building local and regional supply chains, offering the reader a blueprint for eating sustainably. Zelana Montminy ’04 explains the science behind focus and distraction and gives strategies to control our attention and improve our mental clarity.

Zelana Montminy ’04 explains the science behind focus and distraction and gives strategies to control our attention and improve our mental clarity. Krystyn Moon ’97 examines the history of Alexandria’s African American community, focusing on its relationship with the federal government.

Krystyn Moon ’97 examines the history of Alexandria’s African American community, focusing on its relationship with the federal government. In this work of historical fiction, Ginny Kubitz Moyer ’95 tells the coming-of-age story of a young seamstress living in San Francisco during World War II.

In this work of historical fiction, Ginny Kubitz Moyer ’95 tells the coming-of-age story of a young seamstress living in San Francisco during World War II. A deadly asteroid is about to strike Atlantis in this prequel to The Atlantis Grail fantasy series by Vera Nazarian ’88.

A deadly asteroid is about to strike Atlantis in this prequel to The Atlantis Grail fantasy series by Vera Nazarian ’88.

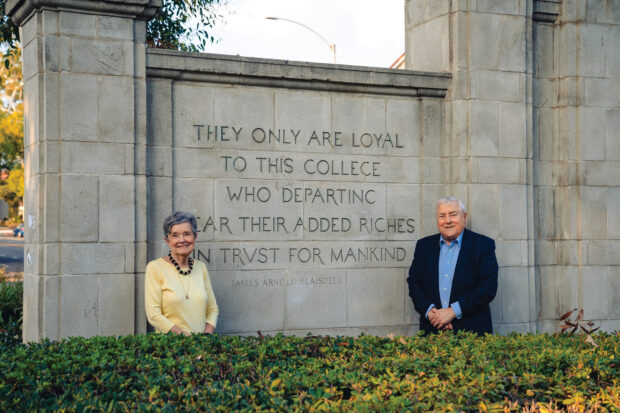

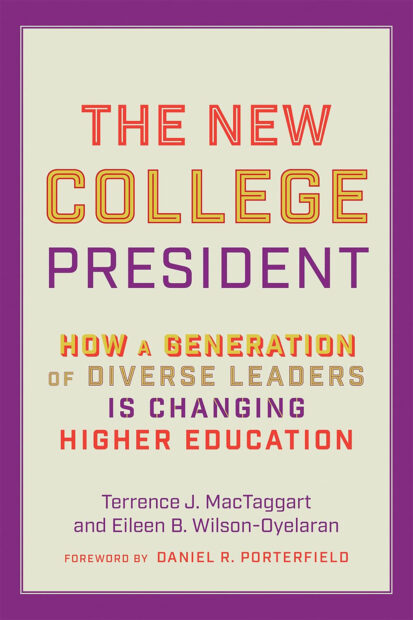

The book, “The New College President: How a Generation of Diverse Leaders Is Changing Higher Education,” co-written with Terrence MacTaggart and published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, profiles seven university leaders and describes the skills and personal qualities they possess that have made them successful.

The book, “The New College President: How a Generation of Diverse Leaders Is Changing Higher Education,” co-written with Terrence MacTaggart and published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, profiles seven university leaders and describes the skills and personal qualities they possess that have made them successful. During her years at Pomona, Wilson-Oyelaran was a galvanizing figure who was instrumental in creating The Claremont Colleges’ first Black Student Union in 1967 and the Black Studies Center in 1969. She says that she’s deeply encouraged by how her generation’s efforts transformed higher education, both in terms of what the student body looks like, and in the expanded breadth of the curriculum.

During her years at Pomona, Wilson-Oyelaran was a galvanizing figure who was instrumental in creating The Claremont Colleges’ first Black Student Union in 1967 and the Black Studies Center in 1969. She says that she’s deeply encouraged by how her generation’s efforts transformed higher education, both in terms of what the student body looks like, and in the expanded breadth of the curriculum.

Moon

Moon

Night

Night Los escritores y el flamenco. La lucha antifranquista (1967-1978)

Los escritores y el flamenco. La lucha antifranquista (1967-1978) I Am We

I Am We Disaster Nationalism

Disaster Nationalism The New Rules of Influence

The New Rules of Influence Hidden Healers

Hidden Healers Abigail and Alexa Save the Wedding

Abigail and Alexa Save the Wedding Animating the Victorians

Animating the Victorians I Trust Her Completely

I Trust Her Completely Deadly Vision

Deadly Vision

Challenging Boys

Challenging Boys This pragmatic guide written by Steven Ferrey ’72 helps legal practitioners navigate the nuanced dynamics involved in shifting policy around renewable energy.

This pragmatic guide written by Steven Ferrey ’72 helps legal practitioners navigate the nuanced dynamics involved in shifting policy around renewable energy. The Sides of the Sea

The Sides of the Sea Intoxicating Pleasures

Intoxicating Pleasures Old King

Old King By the Shore of Lake Michigan

By the Shore of Lake Michigan A Golden Life

A Golden Life Abortion Rights Backlash

Abortion Rights Backlash