It’s early May, and Pomona students are stressing out in droves over final papers and upcoming exams. But never fear—help is near, with a wagging tail and a droopy ear. During the annual “De-Stress” event on the Smith Campus Center lawn, students take a little time off from studying to do something that is medically proven to reduce stress—that is, pet a puppy. For those allergic to doggie fur, the event also includes games, frozen snacks and plenty of pizza and camaraderie.

It’s early May, and Pomona students are stressing out in droves over final papers and upcoming exams. But never fear—help is near, with a wagging tail and a droopy ear. During the annual “De-Stress” event on the Smith Campus Center lawn, students take a little time off from studying to do something that is medically proven to reduce stress—that is, pet a puppy. For those allergic to doggie fur, the event also includes games, frozen snacks and plenty of pizza and camaraderie.

Articles Written By: Nate Stazewski

Puppy Love

A View Through the Bars

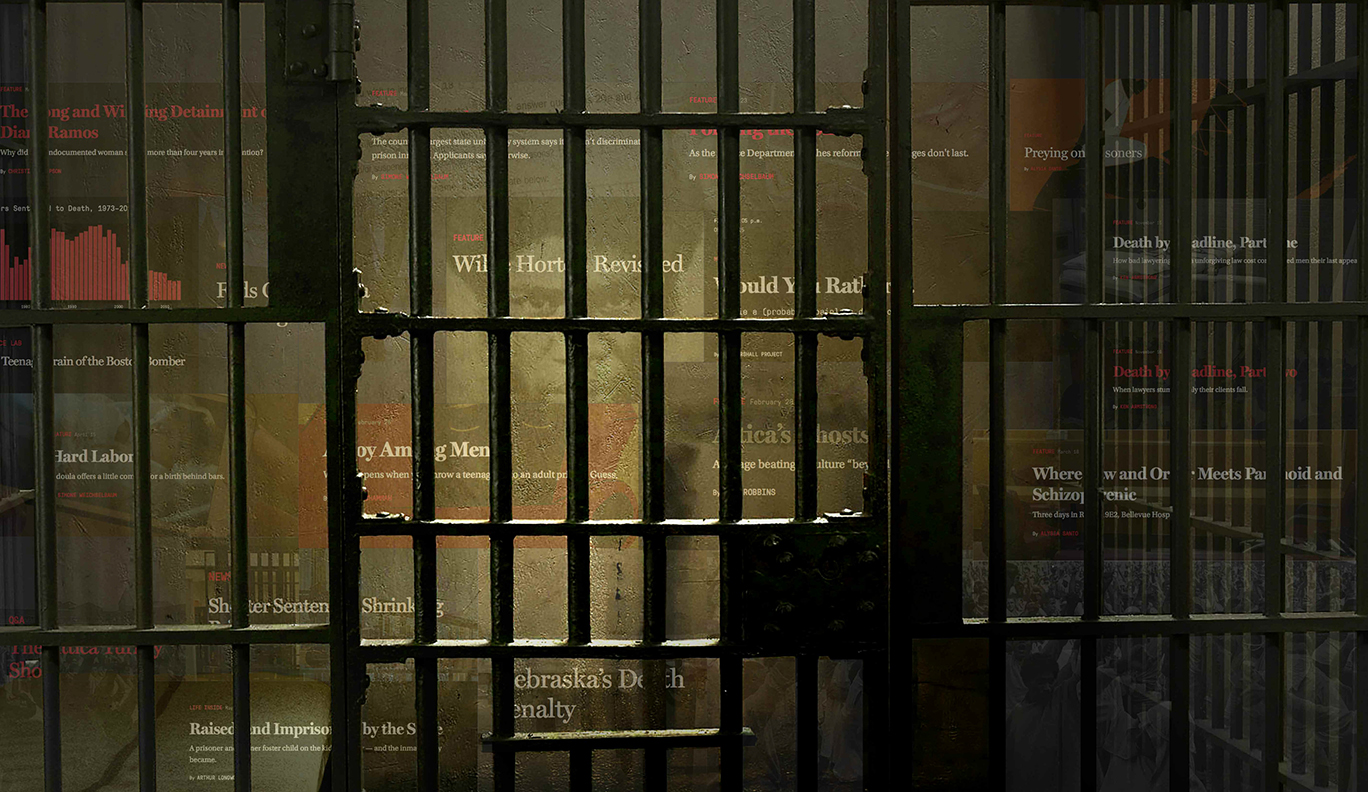

IT’S A CHILLY MARCH morning in Manhattan—the kind of grey, slushy Wednesday that can make even the most optimistic New Yorker wonder if winter will ever end. But for Bill Keller ’70, it might as well be spring.

IT’S A CHILLY MARCH morning in Manhattan—the kind of grey, slushy Wednesday that can make even the most optimistic New Yorker wonder if winter will ever end. But for Bill Keller ’70, it might as well be spring.

The previous weekend, Keller’s former employer, The New York Times, ran a 7,500-word article about the brutal beating in 2011 of an inmate by guards at the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York. Three of the guards were scheduled to stand trial on Monday for multiple felonies, including first-degree gang assault. All had rejected plea bargains.

The story was reported by investigative journalist Tom Robbins for The Marshall Project, the nonprofit digital news outlet dedicated to criminal justice issues that Keller has edited since it launched in November of last year; and it was posted to the Times and Marshall Project websites before appearing on the front page of the newspaper’s Sunday print edition, complete with striking photos by Times photographers Chang Lee and Damon Winter. (Keller, who has been a trustee of the College since 2000, says he spent “a lot of time” dashing in and out of a board meeting in Claremont the previous Friday, shepherding the piece through publication.) On Tuesday, Robbins and Times reporter Lauren D’Avolio filed another story: all three guards had suddenly accepted a deal from prosecutors, pleading guilty to a single misdemeanor and quitting their jobs in order to avoid jail time.

From a purely journalistic perspective, the two articles packed quite a wallop, reverberating across the Internet and stimulating commentary in a variety of other media. And it’s not inconceivable that the first, lengthy story helped create the environment that made the second, shorter one come to pass; maybe, Keller mused in his Midtown office, a series of masks representing former Russian leaders gazing down at him from the wall, the guards decided to accept a plea deal because the weekend feature made it clear that prosecutors had a strong case against them.

The Marshall Project was founded by Neil Barsky, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, documentary filmmaker, and hedge-fund manager whose interest in criminal justice was piqued a couple of years ago by two books: Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, which examines the mass incarceration of African Americans; and Gilbert King’s Devil in the Grove, about Thurgood Marshall’s defense of four young black men who were falsely accused in 1949 of raping a white woman. (The Marshall Project was named for the late Supreme Court justice.) Barsky was raised in a politically active household—both parents were involved in the civil rights movement—and he retains a belief in the power of journalism to effect social change. He also feels that the American public has become inured to the fact that the nation’s criminal justice system is, as he says, “scandalously messed up.” So he decided to use digital journalism to lend the subject of criminal justice reform the urgency it deserves. “The status quo is not defensible,” Barsky says. “The country needs to see this issue like the house is on fire.”

Barsky didn’t know Keller personally, but in June 2014, he shot him an email to see if he might be interested in signing on as editor-in-chief. The two met for breakfast; Keller agreed; and then, as Barsky puts it, “all hell broke loose.”

“Bill’s hiring put us on the map right away with funders and with other reporters and editors who wanted to work with us,” Barsky says. It also stirred up a great deal of media attention, with articles about Keller, Barsky and The Marshall Project appearing long before the site actually launched.

This should come as no surprise. Keller is one of the most familiar and respected figures in American print journalism: Over the course of his 30 years at the Times, he won a Pulitzer for his coverage of the fall of the Soviet Union; served as bureau chief in South Africa during the end of apartheid; held the position of executive editor for eight years; and ended his run at the paper as a columnist. His decision to move to a nonprofit digital enterprise evoked comparisons with Paul Steiger, who left his job as managing editor of the Wall Street Journal to found ProPublica, now the largest and best-known nonprofit digital newsroom in the country; and it generated a commensurate amount of buzz.

For Keller, running an editorial staff of 20 after several years of solitary column writing represented a welcome return to what he calls the “adrenaline and collegiality” of chasing news. Just as importantly, it meant working in an area where there was a real opportunity to effect change—there is broad bipartisan support for criminal justice reform these days—and to practice accountability journalism, probing public institutions to see if they are fulfilling their responsibilities. This, he adds, is distinct from advocacy: The Marshall Project does not promote specific legislative reforms, nor does it take a moral stand on issues like drug policy or capital punishment. (He does admit, however, that walking the line between advocacy and accountability can sometimes be uncomfortable, and says that he must occasionally keep his staff from crossing it; but as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once memorably said of pornography, Keller claims to know advocacy when he sees it.)

Bill Keller ’70 at the New York office of the Marshall Project

There was also, Keller says, a certain appeal to building an organization from scratch, without the ample safety net afforded by The New York Times, and in managing a relatively small operation. “I can talk to pretty much everyone on my staff if I want to, which is nice,” Keller says—and presumably quite different from the Times, where he edited a staff of 1,250.

In fact, Keller had just come from The Marshall Project’s weekly editorial meeting. A clutch of reporters and editors crowded into Barsky’s office in his absence, some sitting on the floor, others taking up positions on top of a low-slung filing cabinet. Keller presided with genial authority, asking questions, soliciting opinions, and sifting the criminal justice news of the day for potential stories.

That news, as anyone with eyes to see or ears to hear can attest, has been coming thick and fast of late. The Marshall Project was conceived before Eric Garner died while being subdued by police officers in New York City; before Michael Brown and Walter Scott were fatally shot by police officers in Ferguson, Mo., and North Charleston, S.C.; and before Freddie Gray died of injuries sustained while in police custody in Baltimore. And it came into being as those and similar events sparked what has been described as the most significant American civil rights movement of the 21st century, inspiring a concomitant deluge of stories about crime, punishment and America’s failure to manage either one particularly well.

But criminal justice has always represented an unusually rich vein of material for investigative journalists, and that, too, appealed to Keller. The sheer scope of the topic was evident at the Wednesday meeting: Andrew Cohen, who edits “Opening Statement,” the site’s morning e-newsletter, talked about the release of a report by the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing; news editor Raha Naddaf described a possible collaboration with a highly regarded print magazine on deteriorating conditions at New York City’s Rikers Island jail complex; and Keller brought up the case of the Kettles Fall Five, a group of medical marijuana growers in Washington State who face federal drug charges. There was talk of immigration law, of data-driven reporting, and of recent revelations regarding just what kinds of information federal prosecutors are obliged to share with defense attorneys.

Several of those stories would make their way onto the site over the next month or so, as would a dizzying array of others. Indeed, in a single week in late April, The Marshall Project ran pieces that dissected the career of Baltimore police commissioner Anthony Batts; examined the treatment of transgender inmates and investigated standards of care for diabetic ones; considered the miserable record of the FBI’s forensics labs and the long-term efficacy of reforms imposed on local police forces by the Department of Justice; and invited readers to take a quiz to find out which are killed more humanely: pets or prisoners. (Answer: pets.) “For a niche subject, this is a very big niche,” says Keller, who together with staff writer Beth Schwartzapfel filed a story in mid-May about Willie Horton, the convicted murderer and rapist whom George H.W. Bush used to pummel Michael Dukakis in the 1988 presidential election.

Much of the site’s original reporting covers topics that remain underreported elsewhere, or provides added context to ones that are already trending. There’s no denying that the latter have proliferated wildly over the past year or so: “Opening Statement” typically includes links to pieces produced not only by other criminal justice outlets like The Crime Report and The Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, but also by publications such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Guardian; a host of independent blogs and progressive news sites; and just about every major newspaper in the United States.

The attention currently being paid to criminal justice represents a sharp reversal following years of declining coverage. That decline, says Stephen Handelman, who edits The Crime Report and directs the Center on Media, Crime and Justice at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, resulted from two principal phenomena: falling crime rates, which made the topic a “spectator sport” for many middle-class Americans; and turmoil in the news business, which led to a reduction in resources, including the number of reporters with the knowledge and experience required to tackle complex criminal justice stories. Despite the proliferation of digital tools for gathering and distributing news and information, solid investigative reporting still requires old-fashioned shoe-leather, which in turn requires both time and its correlate, money. And investigative reporting that focuses on criminal justice stories that may unfold over weeks or months or even years—stories that require reporters to scrutinize sprawling institutions like the federal court system or state correctional facilities and that involve untangling the complex web of legal, social and political factors at play in issues like the mass incarceration of black men, the detention of undocumented immigrants, the war on drugs and the use of prisons as holding pens for the mentally ill—requires a lot of both.

Which brings us, inevitably, to the “nonprofit” part of “nonprofit digital news outlet.” The word is by no means a synonym for impoverished; some of the most robust news organizations in the country (NPR, The Associated Press) are nonprofits. Nonetheless, there are concerns about the long-term prospects of the smaller digital nonprofits that sprouted like mushrooms in the wake of the Great Recession, when the short-term prospects of traditional news media appeared to be particularly dismal. A 2013 study of 172 nonprofit digital news outlets by the Pew Research Center suggested a guardedly optimistic attitude, with most reporting that they were in the black. But the study also found that many of those same outlets were reliant on one-time seed grants from foundations, and lacked sufficient resources to pursue the marketing and fundraising activities that could help them become more financially stable. “Nonprofit journalism isn’t going away any time soon,” says Jesse Holcomb, a senior researcher at the center who worked on the report. “But that doesn’t mean there’s been a tipping point in terms of achieving a sustainable approach.”

Research by the Knight Foundation indicates that the most successful nonprofit news organizations seek to diversify their funding; invest in marketing, business development and fundraising; and build partnerships with other organizations to expand their audiences and bolster their brands. Judging by those criteria, The Marshall Project appears to be on solid footing. The site has a long list of donors, some of whom have committed funds for two or three years, and a dedicated business staff. Keller and Barsky are considering a wide range of alternative revenue sources, including memberships, conferences, and sponsorships—though advertising might be a tougher row to hoe. (“Advertisers aren’t dying to advertise their products next to stories about prison rape,” Keller says.) And thanks no doubt in part to the Keller Effect, the site is not hurting for partners.

In addition to the Attica piece, The Marshall Project has published stories in conjunction with The Washington Post, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and Vice, which Keller describes as “a direct pipeline to a younger audience.” It also has projects in the works with 60 Minutes and This American Life, and is in talks with several other outlets, including Stars and Stripes, The Weather Channel, and the statistics-driven news site 538.org.

In some ways, Keller says, it’s easier to do everything yourself. But collaborations with other outlets help build the site’s credibility, and allow it to leverage the resources of different organizations. (The Times, for example, contributed photography to the Attica piece, which can be costly, while other partners might provide legal services or help cover travel expenses.) Most importantly, such partnerships ensure that The Marshall Project’s reporting, which Keller describes as “journalism with a purpose,” will reach the largest possible audience.

“The aim,” says Keller, “is to get these issues onto the larger stage. And for that, you need a megaphone.”

Little Bridges at 100

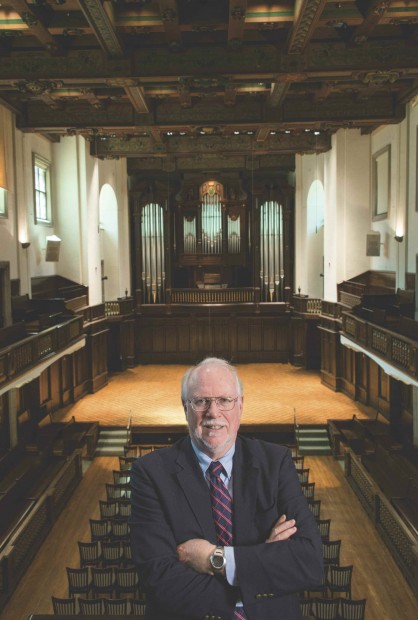

BRIDGES HALL OF MUSIC—Pomona’s signature building that turns 100 this year—has been a part of my life for half of that span, since I first arrived on campus as a freshman in the fall of 1965.

Bridges Hall of Music

In the days before the construction of the Thatcher Music Building, the College Choir rehearsed in the hall daily during the lunch hour; the Band rehearsed on Monday and Wednesday afternoons; the Orchestra and the Men’s and Women’s Glee Clubs rehearsed in the evenings. Large classes were also scheduled there, and I remember taking Professor Karl Kohn’s Music 54 in Bridges during my second semester. The College Church, in whose choir I also sang, met there on Sunday mornings, and I took organ lessons from “Doc” Blanchard on the Moeller Organ. And, of course, all concerts were given there.

Professor Graydon Beeks ’69 recalls singing with the Choir at the 50th anniversary of Little Bridges in 1966. A member of the music faculty since 1983, Beeks has also served as building manager since 1984.

My freshman year witnessed the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the opening of Little Bridges, which culminated in a performance of Mozart’s Requiem, K626 by the Choir and Orchestra. I did not realize the significance of this celebration at the time, even though there is a note about it in the program. I remember the event mainly as one of the last concerts conducted by Professor Kenneth Fiske, the conductor of the orchestra since 1936, before his retirement the following year.

Over the next four years I attended or participated in innumerable rehearsals, concerts, classes and church services in Little Bridges, but in many ways the most remarkable event was the appearance of “The Web.” This was an intricate assemblage of thin wire strung between the railings of the balcony by a number of students—many of them my classmates—working in secret during the wee hours of the morning and sprung on an unsuspecting public. Professor William F. Russell, the long-serving choir and band director and chair of the Music Department, had an impish sense of humor himself and was pleased with the ingenuity and execution of the project. Since it seemed to improve the acoustics of the hall, it was left in place for some time, until it collected a substantial amount of dust and the wire began to break, at which point it was removed.

Shortly after I graduated in June 1969, a report on the state of College buildings that was prepared for President David Alexander during his first months in office revealed that Bridges Hall of Music did not meet current standards with regard to earthquake safety, and the building was closed. Thought was apparently given to demolition because of the anticipated cost of bringing the building up to code. Fortunately, Trustee Morris Pendleton was able to find the original plans and discovered that the building was built well above code in 1915, reducing the cost of retrofitting by a substantial amount. The funds were raised in 90 days, primarily from loyal alumni, many of whom had been married in the hall; their names are preserved on large panels in the lobby and on small plaques attached to the bench seats.

Professor Tom Flaherty (here performing with his wife Cynthia Fogg), has composed dozens of pieces to be performed at Little Bridges, including “Millenium Bridges” a crowd-participation piece written to celebrate the reopening after the 2000–01 renovation.

In addition to seismic retrofitting, acoustical work was done to increase reverberation and prevent the loss of bass frequencies. The stage was enlarged to better accommodate collaborations by the Choir and Orchestra, which had become an annual feature since 1962. A loading dock was added on the west side, eliminating the need to load pianos and other large instruments via a temporary ramp. The hall also gained air conditioning, a new lighting system and new chairs on the main floor.

This was the state of Little Bridges when I returned to Claremont in 1981 and resumed playing in the Band and singing in the Choir. In 1983, I was hired to conduct the Band, and the next year I also took over the supervision of the scheduling and maintenance of the Music Department facilities, including Little Bridges, which I have continued to do until the present.

Many things had changed while I was away. The College Church was no more, and classes were no longer held in Little Bridges. Because of the installation of air conditioning and the threat of vandalism to valuable instruments, the building was no longer left unlocked in the daytime. The Choir and Glee Clubs now rehearsed in Lyman Hall, the smaller auditorium in the new Thatcher Music Building, and the instrumental ensembles, which now included a Jazz Band, rehearsed in Bryant Hall (although the Orchestra and the Concert Band were soon to move back to Little Bridges for evening rehearsals). Most of the student ensembles continued to perform in Little Bridges, and their number was increased in 1993 with the addition of a Javanese Gamelan, using rented instruments, followed in 1995 by the acquisition of the College’s own Balinese Gamelan, “Giri Kusuma” (“Flower Mountain”).

Noted composer and Professor Emeritus Karl Kohn and his wife, Margaret Kohn, came to Pomona in 1950 and gave their first two-piano recital in Little Bridges 65 years ago.

Convocations were now held in Little Bridges rather than Big Bridges, but overall, fewer students had extensive contact with the building, and the number of alumni weddings steadily declined. Finally, most organ practice and performance had moved to the new von Beckerath instrument in Lyman Hall, and despite some reconfiguration in the 1970s and re-leathering in the 1980s, the organ in Little Bridges was beginning to show its age.

There have been many distinguished concerts in Little Bridges in the years since my return to Claremont, but what stands out most clearly in my mind are the concerts related to the celebration of the College’s Centennial in 1987–88. These included performances of newly composed works by Pomona College alumni and a performance by the Pomona College Choir and Orchestra of the Requiem by Maurice Duruflé and of a new work, “To the Young,” commissioned from Pomona alumnus Vladimir Ussachevsky ’35, who had also written the work commissioned to celebrate the College’s 50th anniversary. The Centennial concert was conducted by distinguished alumnus Robert Shaw ’38 and featured Professor Gwendolyn Lytle as soprano soloist.

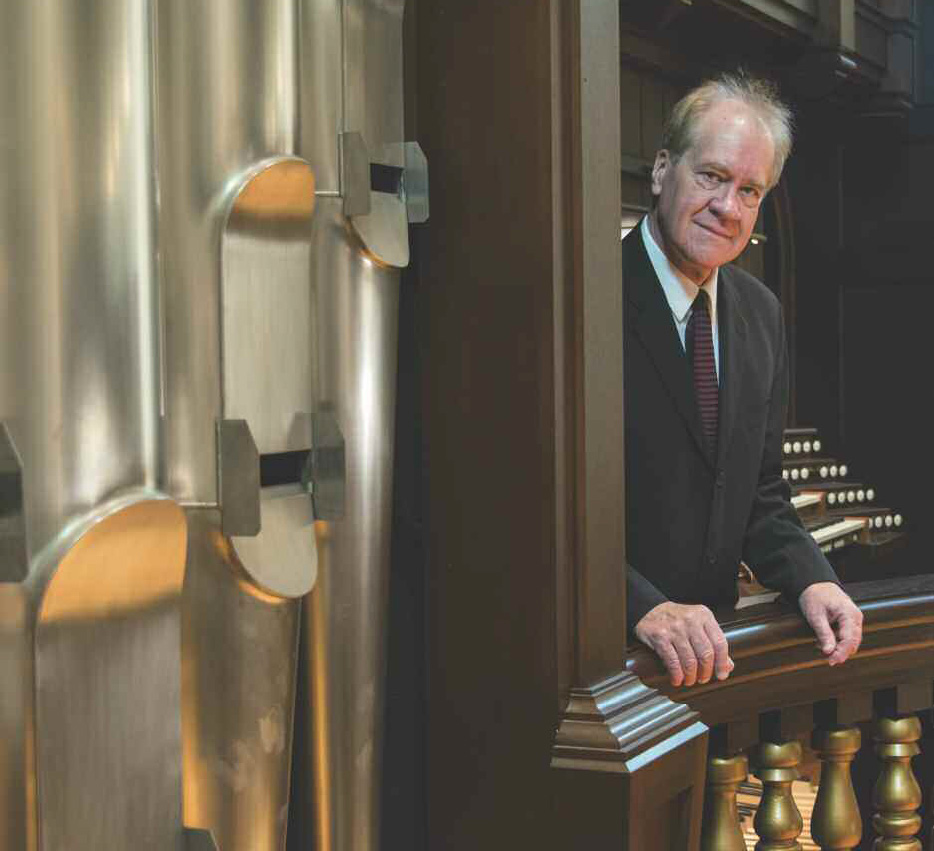

Professor and College Organist William Peterson oversaw the installation of the C.B. Fisk pipe organ, in 2000–01 as part of a full renovation. The instrument has 3,519 pipes ranging from a half-inch to 32 feet long.

I would argue that the single most important event to take place during my 32 years on the Music faculty was the installation of the Hill Memorial Organ, built by C.B. Fisk of Gloucester, Mass., as part of another renovation in 2000–01. This project, spearheaded by College Organist William Peterson, required many years of detailed planning. It involved extensive acoustic alterations, including a quieter air conditioning system and the installation of mass above the ceiling to prevent sound from escaping into the attic (where some enterprising students used to go to listen to concerts). The addition of wings on either side of the building allowed for the installation of an elevator, an accessible restroom and additional storage. The repositioning of air conditioning ducts made it possible to remove some walls added in 1970 and reopen four windows that had been closed off at that time, while the ingenuity of the architect permitted the addition of musician’s galleries above both sides of the stage. Finally, the imaginative design of the new organ case maintains several significant aspects of the original case. All these things, taken together, mean that the current configuration of Little Bridges actually resembles more closely the interior layout of the hall as originally designed by Myron Hunt, while also incorporating the improvements made in 1970 and 2000.

It has been a great privilege for me to work in Little Bridges for what has now been just over half my life. I have appeared on the stage as a conductor, singer, percussionist and harpsichord player. In the course of facilitating appearances by others, I have also made appearances as an announcer, a gaffer, an audio engineer, a lighting technician and a caretaker—jobs that are generally done these days by far more qualified people. In the early years, the light settings would occasionally change of their own accord—sometimes during concerts—and we attributed this to the ghost of Mabel Shaw Bridges 1908. Her ghost has not been as active in recent years, and I hope that is because she is happy about the current state of the hall and the way the College maintains and uses this gift that her parents provided in her memory just over a hundred years ago. I hope to have the opportunity to oversee that legacy for a few more years.

LetterBox

In Defense of Amazon

In “Preston vs. Amazon” (PCM Spring 2015) Douglas Preston makes some good points, but in at least some respects his viewpoint is based on an outmoded author/publisher model.

He states: “If authors couldn’t get advances, an awful lot of extremely important books wouldn’t get written.” While this may be true of some books, it is also true that many great books have a terribly difficult time getting past the gatekeepers at publishing houses, who are increasingly looking for blockbusters and who are increasingly unwilling to nurture beginning authors. The list of highly-rated authors who spent years receiving rejection letters before getting published is a lengthy one. These authors weren’t getting advances, and they had to spend countless hours struggling to get published instead of researching and writing books. (William Saroyan, for example, received 7,000 rejections before selling his first short story; Marcel Proust got so many rejections that he gave up and self-published.)

Publishing on demand (such as is offered by Amazon and other publishers) has solved this problem: there are no gatekeepers. Beginning authors can publish anything they want, and see it listed for sale on a variety of sites, including Amazon. Yes, a lot of dross gets published this way. On the other hand, a glance at the books for sale in airports or on various “best seller” lists demonstrates that a lot of dross gets published the old-fashioned way. In the end, for better or for worse, the market—not a publishing house—will decide what lives and what fades away.

If publishers are “venture capitalists for ideas,” venues like Amazon are virtually cost-free incubators for individual thinkers and entrepreneurs (i.e., writers) trying to get their concepts produced and marketed without having to impress a patron. This is not a bad thing.

—David Rearwin ’62

La Jolla, Calif.

Museum Musings

The College has preliminary plans to build an art museum at Second and College where the cottages now stand, across the street from the Seaver Mansion/ Alumni Center where the Claremont Inn, a real community center, used to be located. As a planner and a donor with a long interest in the College, I would like to see a transparent planning process in which this building project serves the broadest possible cultural goals. We have been constructing single-purpose buildings, and they have created a banal, sometimes isolating cityscape of a college, which for the most part hasn’t deployed architecture to generate a cultural edge. I would argue that Pomona students suffer from this deficit. As a college, we need more cultural energy: a Medici city palace with artist residencies, Claremont fellows, comfortable places for visiting dignitaries and scholars should generate this kind of cross-fertilization and nourish the art of conversation. Maybe we would produce more Rhodes Scholars with this conversational energy and the self-confidence it breeds.

Close to the city center, this site is too important just to be an art museum housing a modest collection, including many Native American artifacts now stored at Big Bridges. With the largest endowment per student in the country, Pomona is rich enough to build new buildings without soliciting big donors or their advice. But I would argue that rather than giving administrators the credit for a single-purpose building that can be done quickly, this site is strategically important for constructing a stronger culture with ties to the community and to the other colleges. It requires real leadership to build those ties and a cultural confidence that many academics lack. An elegant dining room serving the trustees, literary and artistic societies (yet to be formed as they are at Harvard and Yale), community leaders and donors, a cinema café (acknowledging that filmic literacy is part of a Pomona education), community rooms that host endowed lecturers, as at the CMC Athenaeum, and perhaps a used book store will give the site a more dynamic spirit.

It took protests from Yale students in the 1960s to change the plans of the award-winning architect, Louis Kahn, and the donor, Paul Mellon, to transform the Yale Center for British Art on Chapel Street into a lively street presence, with café and book store. Pomona is less urban and, I would argue, less urbane, and there may not be a student constituency that could demand more of the building than an architectural prize or many trustees that care about these values, but let’s try with at least an open discussion. Culture is a sense of mutual responsibility between centers of power. It is time that these centers started having a conversation at Pomona. Now, that is a project for “daring minds,” the current slogan used to raise money for that conservative and safe goal of scholarships. Let’s go further. Let’s make Pomona a scintillating place. Mixed-use buildings are a beginning.

—Ronald Lee Fleming ’63

Cambridge, Mass.

Remembering Jean Walton

The latest issue of PCM introduced Professor Ami Radunskya and a story about women and math. I wonder if she knows the name, Dean Jean Walton, a woman of major importance to Pomona College and its education of women? Part of me wants to write a long piece, but if I try, this will never get sent. Besides, just a quick review of old issues of your magazine will provide information as to how old I am and how old the story of the unique issues of women and the College truly is: Pomona Today Illustrated for July 1973 has an article called “Choices,” and the summer 1990 issue of Pomona College Today has an article called “Rethinking Roles: Women’s Studies Challenges Belief Systems.” My files also include an article from the Winter 2005 PCM titled “End of the Weigh-In,” by Helen Hutchison ’74, remembering a Jean Walton experience.

What I have tended to forget, partly because I never took a math class at Pomona, is that Jean Walton’s Ph.D. was in mathematics from the University of Pennsylvania. I actually have a copy of her thesis. Although it is unreadable to the likes of me (words like “and,” “but” and “to” were the few I recognized), I love having it. If any of you, including Professor Radunskya, are curious about Dean Walton, (she retired as a vice president, but during my years as a student and when we did the early Choices weekends, she was Dean) one interesting book that has a whole chapter written by Jean is: The Politics of Women’s Studies; Testimony from 30 Founding Mothers, edited by Florence Howe. The heading of her chapter, which is in Part I, is “‘The Evolution of a Consortial Women’s Studies Program,’ Jean Walton (The Claremont Colleges).” I write all this because somehow it is important that these sorts of connections don’t get lost. It might make the newer faculty a little wiser and more compassionate about their aging ground-breakers.

—Judy Tallman Bartels ‘57

Lacey, Wash.

Remembering Jack Quinlan

Professor Quinlan was appointed Dean of Admissions in 1969, a critical time in the college’s history. Chicano and African American students felt we were vastly underrepresented in the enrollment at the time. Members of MECHA, including myself, and the Black Students Union were pressing the College to increase its diversity. I had the privilege of serving on a subcommittee on Chicano admissions with Dean Quinlan. Although our relationship was initially adversarial, I soon found John to be genuinely committed to the goal of diversity.

The fact that the enrollment of Pomona College today roughly mirrors that of the nation as a whole is in great part due to Dean Quinlan’s commitment to “quality and diversity,” first demonstrated all those decades ago.

—Eduardo Pardo ‘72

Los Angeles, Calif.

Athletes and Musicians

The PCM reported in the Spring 2015 issue that Kelli Howard ’04 has been inducted into the Pomona-Pitzer Athletic Hall of Fame, a well-deserved honor. It is worth noting that Kelli and her doubles partner, Whitney Henderson ’04, were also four-year members of the Pomona College Band, playing tenor saxophone and trombone respectively. Combining intercollegiate athletics and serious music-making is difficult at a school like Pomona, with its heavy academic demands, but as Kelli and Whitney demonstrated, it can be done.

—Graydon Beeks ’69

Professor of Music and Director of the Pomona College Band

Claremont, Calif.

[Alumni and friends are invited to email letters to pcm@pomona.edu or “snail-mail” them to Pomona College Magazine, 550 North College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711. Letters are selected for publication based on relevance and interest to our readers and may be edited for length, style and clarity.]

Champion Times Nine

A FAMILIAR CLICHÉ for highly successful athletes is that they may need bigger mantelpieces to hold their many trophies. Vicky Gyorffy ’15 may need an extra fireplace.

As a member of the women’s swimming and diving and women’s waterpolo teams, Gyorffy was a part of nine SCIAC Championships. Her 800-yard freestyle relay team took first at the SCIAC Championships three years in a row. As an individual, she swept the 100- and 200-yard freestyle events in her senior year. Meanwhile, her women’s water polo team won at least a share of the SCIAC title in all four of her seasons.

And that’s not all. Gyorffy also advanced to the NCAA Division III Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships in 2014 and 2015, earning honorable-mention All-America honors, and she was an honorable mention All-America selection in water polo, while helping the Sagehens to the NCAA Championships in 2012 and 2013.

It is easy to see how Gyorffy got hooked on water sports. Her older sisters were swimmers and water polo players in high school, with Janelle graduating from Pomona in 2009 after playing both sports and Rachele graduating from Princeton in 2013 after focusing solely on water polo. Both competed in the NCAA Women’s Water Polo Championships in 2012 and 2013.

With a strong background in aquatic sports, and from a high-achieving family academically, Gyorffy had a lot of options, but ended up following in Janelle’s footsteps at Pomona, although sports wasn’t a major part of her decision.

“I wasn’t even sure I wanted to compete in sports in college, which is sort of ironic since I ended up competing in two of them,” she says. “I was just looking for a small school that was great academically, and I didn’t want to be too close to home. I think Janelle probably convinced me that the 5C environment was unique and that choosing Division III sports was a nice way to go. It’s really competitive, but not the super-intense environment than larger schools can be.”

In addition to all the athletic championships, Gyorffy has prospered academically, graduating in May as an economics major with a computer science minor. In 2014, she had a unique chance for a summer internship at Twitter headquarters working with the Girls Who Code immersion program, a six-week course in which she taught computer programming to high school girls.

“The Girls Who Code internship came about through the [Career Development Office’s] Claremont Connect program,” says Gyorffy. “Pomona was amazing, the way they helped fund that internship and make it a reality. The internship only offered a small stipend and the Bay Area is expensive, so I don’t think I could have done it without Pomona’s assistance.”

Gyorffy will start a full-time job next year as a tech consultant with a software company, which will allow her to apply both her economics degree and her passion for technology. “The job is sort of a hybrid between the business side and the software side. You need a tech background, but you can act as sort of a bridge between the software developers and the clients.”

Some people find balancing one sport and academics to be difficult. Gyorffy competed in two sports, which overlapped in the spring, and still achieved great things in the classroom. But she insists it wasn’t as challenging as it seems.

“Balancing academics and athletics wasn’t too difficult,” she says. “I like being busy and doing different things, and the coaches are great here at allowing you to focus on your academics first. What was difficult was balancing the overlap between swimming and water polo, especially the last couple of years. Going to nationals in swimming extended the winter a little more.”

The time spent swimming paid dividends her senior year with her 100-200 sweep at the SCIAC Championships. “I think this year I just wanted to get on the podium really badly, since it was my last chance, and I ended up winning. I think winning the 200 may have been my favorite moment of my athletics career, since I wasn’t expecting it.”

She won the 200 by just four-hundredths of a second, as she finished in 1:53.77, almost a second and a half ahead of her finals time from a year before. The next day, she added a more comfortable win (by 2/3 of a second) in the 100 with a time of 52.67, a full second faster than a year prior.

Gyorffy had a storybook ending to her swimming season, but she ended her water polo career with the opposite feeling. After winning the SCIAC title outright their first three seasons, she and her six classmates all had visions of making it four in a row and returning to the NCAA Championships. But after going undefeated in the SCIAC during the regular season, they were upset in the finals of the SCIAC Tournament by Whittier 7–6. The two teams were officially co-champions, but the loss brought Pomona-Pitzer’s season to a premature end.

“Of course, we were all disappointed, but we are not going to think of one game when we look back,” she says. “It’s going to be all about the journey of the whole four years. Maybe it wasn’t the storybook ending we had hoped for, but we’ve been on the other side of those close games many times, so maybe it was only fair that it came back around.

“For me personally,” she says, “I think losing one maybe makes me appreciate the three we did win even more now. It’s hard to win a championship, and a lot of athletes give it their all and never get the chance to experience it.”

Much less nine times.

Pomona-Pitzer Cracks Top 50 in Director’s Cup Rankings

For the first time in almost 20 years, Pomona-Pitzer Athletics reclaimed its spot in the top 50 nationally in the 2014–15 Learfield Sports Director’s Cup.

The Sagehens ranked 49th nationally (out of 332 NCAA Division III institutions) jumping from 63rd last year and 117th in 2012-13 and placing them second among SCIAC institutions. It is the highest finish for Pomona-Pitzer Athletics in the Director’s Cup standings since a 33rd-place finish in 1996–97.

Sponsored by the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics (NACDA), the Director’s Cup is a program that honors institutions maintaining a broad-based program and achieving success in many sports, both men’s and women’s. The standings are calculated via a points system based on how teams finish in their national tournaments.

Pomona-Pitzer had a successful academic year from start to finish, with five teams, as well as numerous individuals, qualifying for the NCAA Championships.

In the fall, men’s soccer won the SCIAC Postseason Tournament to advance to the NCAA Division III Championship for the first time since 1980. Men’s cross country earned a team qualification to the nationals for the third year in a row, by taking a second-place finish in the NCAA West Regionals, and ended in 17th place, the team’s highest finish since 1982. Maya Weigel ’17, meanwhile, earned All-America honors for the women’s cross country team with a 22nd place finish, after claiming first place at the West Regionals.

The winter saw a strong season from the men’s and women’s swimming and diving teams, which both finished second in the SCIAC and had national qualifiers. In his first year, Mark Hallman ’18 earned All-America honors by qualifying for the finals in the 200-yard freestyle. For the women’s swimming and diving team, the 800-yard freestyle relay team of Vicky Gyorffy ’15, Maki Tohmon ’17, Kelsey Thomas ’18 and Victoria Vanderpoel ’18 earned All-America honors as well.

The Sagehens made their biggest leap in Director’s Cup standings during the spring semester, thanks to three teams that advanced to the round of 16 in the NCAA Division III tournaments.

Women’s lacrosse reached the round of 16 with its first-ever NCAA tournament win, defeating SCIAC rival Occidental at home after winning its first-ever SCIAC title by four games. Men’s and women’s tennis both moved on to the NCAA Regional Finals in May after earning top-10 rankings in the regular season, with the men reaching as high as third and the women as high as seventh. Men’s tennis defeated Texas-Tyler in the regional semifinals to reach the round of 16, while women’s tennis earned a win over Whitman. In addition, Connor Hudson ’15 qualified for the NCAA Division III Championships both in singles and in doubles after he and doubles partner Kalyan Chadalavada ‘18 reached the finals of the ITA Small College nationals in the fall, earning All-America honors. On the women’s side, Lea Lynn Yen ’16 and Grace Hruska ’18 qualified for the NCAA Championships in doubles.

Women’s water polo, which is not calculated in the Director’s Cup standings due to the small number of participating teams, added to the spring success for Pomona-Pitzer by tying for the SCIAC title with a 10-1 league record, the fourth year in a row that it has earned at least a share of the conference crown.

In addition to team successes in the spring, Weigel completed a fall-spring All-America sweep by finishing in seventh place nationally in the 800 meters for the women’s track and field team, while John Fowler ‘16 earned a top-10 finish (ninth) in the 5,000 meters. Tiffany Gu ’16 also earned a national qualification for the women’s golf team, finishing 30th out of 110 at the NCAA Division III Championships.

The late push in the spring enabled the Sagehens to pass Redlands (56th place) among SCIAC schools.

Not Your Ordinary Help Desk

IF YOU WANT a sneak peek into the personality of Pomona’s Desktop Support Specialist Melanie Sisneros ’94, you might start by visiting her workstation.

Clustered in rows that fan out across every surface are dolls, toys and figurines—a stuffed Fix-It-Felix Jr. plush can be spotted alongside Cruella DeVille. Harry Potter posters paper the walls above her wildly colorful desk.

“I had to downsize when I moved from my old office,” says Sisneros. She points out several well-dressed Bratzillas and explains their rivalry with Monster High dolls.

Also surrounding her work area are boxes and boxes of the latest Apple computers, waiting to be opened and tested. Sisneros is as serious about her work as she is about staying true to herself. A member of the Class of 1994, Sisneros has been working for ITS since she first began work study at Pomona.

“The first job application somebody handed me was for the computer center,” she recalls. “I didn’t know anything about computers, but I needed to fulfill my work study, and it was a job application.”

If you had asked that younger Sisneros whether she thought her career would involve computers, she’d have laughed. “I hated computers when I was little!” she exclaims. “We had this horrible Tandy 1000 RadioShack-brand piece of junk that I could never get to work right. When I got to college, I was quite surprised that I ended up liking computers.” She attributes this interest in part to the late Professor of Psychology William Banks, who was responsible for the acquisition of Sisneros’s first computer of her own, an all-in-one black-and-white Mac with a power supply problem. “That’s when I really started to play and discover,” she recalls.

Sisneros’s method of discovery was entirely her own. “My high school job was working at Long John Silver’s, a fish shop, where I started drawing a comic strip about these little cartoon fish,” she explains. “So once I discovered SuperPaint, an illustration software on my Mac, I started making it on the computer instead. I would print it out and tape it on the door of my dorm room, and people would walk by and read the latest installment.”

Sisneros took to working with computers like one of her cartoon fish to cartoon water. She worked for ITS for four years as an undergraduate before accepting a post-graduation internship, which she held for several years before being hired full-time.

Now, she works as part of ITS’s six-person Client Services team, where her job includes providing desktop support for several academic departments. One of these is the Department of Classics, in which Sisneros was a major. “I’ve always felt that at liberal arts colleges, you learn how to think,” she says. “Regardless of what you study, you learn how to look at things critically. I use that training every day in doing IT support.”

Sisneros spends a big part of her day answering the phone at the ITS service desk, taking walk-ins and responding to help requests submitted through the College website. Much of her job consists of configuring computers, which can either mean connecting remotely or taking time to visit the offices of professors and administrators across campus.

In Sisneros’s eyes, technology is just a tool. One of the joys of her job, she says, is helping users understand the tools at their disposal and match them to their needs. She recalls a brief stint at Computer City in the mid-’90s, where customers would come to her for help “learning computers.”

“What does that mean?” she laughs. “You don’t ‘learn computers;’ you use them for something. I don’t want to learn vacuum cleaners. I want to clean my floor.”

However, what keeps Sisneros excited about her job isn’t just her love of technology and of helping others fit it to their individual needs. “People have jobs where they’re in a rut, day in and day out,” she says. “For me, every phone call is something new. Every person that walks up to the desk brings a new challenge, a new problem to solve. There are new versions of software, new viruses to fix, new everything.”

Raw Truth and Optimism: Chris Burden ’69 (1946-2015)

A yellow and black sculpture in Pomona’s Lyon Garden stands as a silent testimony that artist Chris Burden ’69, who died of cancer at his home in May, started his artistic life as he finished it—as an amazing sculptor. Originally a part of Burden’s senior show, the work was recreated for the 2011-12 exhibition, “It Happened at Pomona: Art at the Edge of Los Angeles 1969-1973.” Burden once said this piece “held the kernel for much of his subsequent work,” says Pomona College Museum of Art Director Kathleen Howe.

In the decade after his graduation from Pomona, Burden was most famous (or maybe infamous) for a series of controversial—and often dangerous—performance art pieces that tested the limits of his courage and endurance. For “Shoot” (1971), an assistant shot Burden in the arm with a rifle while a Super-8 camera recorded the event on grainy film; and in “Trans-fixed” (1974), Burden was nailed face-up to a Volkswagen Beetle in a crucifixion pose. For his master’s thesis at the University of California, Irvine, he locked himself for five days inside an ordinary school locker. Other performance pieces found him shooting at a jet passing overhead, crawling through glass and lying down in heavy traffic on a crowded street.

As Kristine McKenna noted in a Los Angeles Times memorial, “Burden operated like a guerrilla artist, staging his pieces with little advance word. Many of the early performances took place in his studio, documented only by his friends. As artworks, they were experienced largely as rumor—and Burden did manipulate rumor as a creative material. When you heard about a Chris Burden performance, an image would streak through your mind like a blazing comet. That was part of the point.”

In 1979, “The Big Wheel”—in which an eight-foot flywheel made from three tons of cast iron was powered up by a revving motorcycle, then allowed to spin in silence for several hours—marked a dramatic shift in Burden’s artistic approach, combining performance with the kind of witty, inventive and monumental sculptural creation for which he would later become best known. Today, “The Big Wheel” remains in the collection of Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

“The Big Wheel” was followed by other monumental works, almost always involving some jaw-dropping surprise, such as “The Flying Steamroller” (1996), in which a counterbalanced steamroller did exactly what the title suggests, and “What My Dad Gave Me” (2008), a 65-foot skyscraper made entirely of parts from Erector sets.

Perhaps his most iconic work is the ongoing “Urban Light,” an array of restored, antique cast-iron street lamps at the entrance of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The Los Angeles Times notes that it “rapidly became something of an L.A. symbol.” LACMA director Michael Govan told the Times that Burden “wanted to put the miracle back in the Miracle Mile” and said his work “combines the raw truth of our reality and an optimism of what humans can make and do.”

Back at Pomona, where it all started, that yellow and black sculpture now looks fairly tame. And yet, Howe notes, “In this early work you can see the interplay of his engagement with sculpture and aspects of performance. It is a remarkably assured piece from a young artist who was working through the issues that would engage him for the rest of his career.”

Back at Pomona, where it all started, that yellow and black sculpture now looks fairly tame. And yet, Howe notes, “In this early work you can see the interplay of his engagement with sculpture and aspects of performance. It is a remarkably assured piece from a young artist who was working through the issues that would engage him for the rest of his career.”

Pomona College Museum of Art senior curator Rebecca McGrew worked closely with Burden on the “It Happened at Pomona” exhibition, spending many hours with him in his studio. “Meeting Chris Burden and getting to know him is one of the biggest honors of my career,” McGrew says. “In addition to being brilliant, warm and amazingly easy to work with, Chris is one of the most important artists of the 20th and 21st centuries because his visionary and internationally renowned artwork challenges viewers’ beliefs about art and the contemporary world. I am so sorry to not be able to work with him again.”

Helping Out With Speaking Up

GET HER GOING, and Jessica Ladd ’08 will talk effusively about her many positive Pomona memories, from late-night sponsor-group discussions about free will to sunny study sessions on Walker Beach.

In many ways, Pomona directly inspired her career path. She created her own major in public policy and human sexuality, writing her thesis on condom distribution in California prisons and jails. She turned The Student Life’s often-lewd sex column into a thoughtful exploration of topics such as virginity, safe sex and consent.

Perhaps most pivotally, and certainly most traumatically, Pomona was also the place where she was sexually assaulted.

The incident itself was harrowing, but its aftermath was in some respects even more traumatizing. Ladd found herself unsure of how to go about doing basic things like finding emergency contraception and confidentially getting tested for STDs. Worse still, in reporting the assault she felt like a passive and helpless participant, from the tone of campus security’s questioning to uncertainty about how her answers would be used.

“Instead of feeling empowered, I left the situation on the verge of tears,” she says. “It made me realize that many of the tools for improving the process didn’t exist, and sowed the seeds for wanting to create a better way.”

As founder and CEO of Sexual Health Innovations (SHI), Ladd has developed a tool called Callisto that is aimed at making survivors feel more comfortable reporting their experiences. This fall, two institutions will adopt the technology, including the very place where Ladd’s frustrating but illuminating journey first started.

Sexual assault is consistently one of our country’s most under-reported crimes, with upwards of 80 to 90 percent of incidents going undocumented. The reasons range from logistical, to social, to psychological. Victims may be afraid people will think they are lying or exaggerating; they may worry that accusing their acquaintances will ostracize them from social circles; and they may be scared to publicly re-live the experience in a trial where their credibility and character are continuously questioned.

“Because survivors have had their agency stripped in such a severe way, they often feel hesitant to give information to authorities if they think they might lose that agency all over again,” says Ladd, who herself took over a year to report. “We’re trying to create a trauma-informed system that gives them total control over the process.”

Callisto- a tool to help with reporting sexual assault

Callisto lets users file an incident report that can be sent directly to authorities or archived for later. Users can also choose a third option: saving the report such that it only gets filed if their attacker is separately reported by another user.

It’s a clever feature, and not a trivial one. Ladd often cites a 2002 study which found that 90 percent of campus assaults are committed by repeat perpetrators; she’s confident that Callisto has the potential not only to improve the reporting process, but perhaps even to reduce the number of assaults that happen in the first place.

“If authorities could stop perpetrators after their second assault, 60 percent of assaults could be prevented,” Ladd says. “Callisto isn’t the complete answer, but I think it can be a valuable piece in the puzzle.”

One reason to bet on Callisto is that it was developed with direct input from more than 100 college sexual-assault survivors and advocates, in the form of several months’ worth of surveys, focus groups and interviews.

Among the participants was Zoe Ridolfi-Starr, who last year organized a Title IX federal complaint against Columbia University arguing that the institution treats survivors and alleged assailants unequally. She says that, with Callisto, it was clear from the start that SHI truly understood its audience’s needs.

“Survivors can find it overwhelming enough to try to maneuver through all that red-tape before you even add things like PTSD and depression into the mix,” she says. “SHI has shown that they want to go about the process in a way that’s inclusive, intuitive and intentional.”

Callisto’s sleek interface is designed to make it easy to wade through the murky waters of bureaucracy. Questions have explanatory “help text” to clarify why they are being asked and how answers will be used, while the language is chosen with care and sensitivity. For instance, a question about how much the victim had been drinking is couched in reassurances that such answers do not put her or him at fault and will not, say, get her or him in trouble with the school for violating its alcohol policy.

The system’s development has coincided with sexual assault emerging as perhaps the most-discussed issue in all of higher education, from President Obama’s recent “It’s On Us” initiative to the Columbia University student who carried a mattress all year to protest the school’s handling of her assault allegations.

“As far back as 2013, we realized that if there ever was a time for schools to change their programs, it’s now,” Ladd says. “In the past, adopting this might have seemed like an admission that assault is prevalent on campus. Today, it’s seen as forward-thinking.”

The issue has gained prominence even beyond academia, particularly with the many allegations against comedian Bill Cosby. Ladd says that, while such visibility can be valuable, the growing list of women who have spoken out only further highlights the importance of systems like Callisto for survivors who don’t want to go public, or whose assailants aren’t famous entertainers.

“People shouldn’t have to out themselves to the world to get justice,” she says. “Callisto is a service that we’d eventually like to make available to anyone who needs it.”

Ladd’s interest in sexual health evolved from her upbringing on San Francisco’s Castro Street, where she says that it “always seemed like the city around me was dying of AIDS.” An early clouds-parting moment happened in a high school production of “The Vagina Monologues,” when she first learned that there was such a thing as a clitoris.

“It felt as though the world had been conspiring to not let me know about it,” she says. “It made me wonder, ‘what else are they hiding from me?’”

Since then she has dipped her toes into several different sexual-health-related sectors—as an educator, an academic, a policy advocate and even a White House intern—but says that she became disenchanted with all of these approaches as means to actually effect change.

Instead, she looked at companies like Facebook and Google, and realized that a key way to influence people was through technology.

“The Internet allows people to do things that they would normally find socially awkward, from looking at porn and buying sex toys to propositioning threesomes on Craigslist,” she says. “We’ve harnessed that power to make ourselves happier, but why not use it to make ourselves safer and healthier, too?”

Callisto is the flagship initiative for SHI, which Ladd founded while enrolled full-time in Johns Hopkins’ public-health MPH program. SHI has grown from a makeshift website coded by volunteers to a full-fledged 501(c)(3) nonprofit with bi-coastal offices and more than a quarter-million dollars in funding from Google.

This fall, in efforts that are more than a year in the making, Ladd will launch Callisto at two “Founding Institutions”—Pomona and the University of San Francisco.

“We want to make sure that students feel comfortable reporting sexual assaults when they happen,” says Pomona Associate Dean and Title IX Coordinator Daren Mooko. “Callisto is a very creative mechanism for doing so, in a way that puts a lot of control in the survivor’s hands.”

Ladd says she didn’t come into SHI with particularly entrepreneurial intentions, but simply with a problem that she wanted to solve.

“This is something that I have long believed should exist in the world,” she says. “At a certain point I realized that, while I can’t change what happened to me, what I can do is build something that will hopefully help the next person who’s in that same situation.”

Retiring But Not Shy

Rick Hazlett

WHEN ASKED IF PCM could interview him about his retirement, Professor Rick Hazlett suggested that the writer would “have to rappel in to my interview, suspended over a pit of molten lava in a bat cave (or something like that!), where of course I’ll be doing research just for the ‘hell-uvit.’”

He was joking—sort of.

Hazlett is starting his retirement in style: He’s moving to Hawaii. A geology professor at Pomona since 1987, he’s trading Claremont for the Big Island, giving him a prime spot from which to pursue one of his greatest passions: volcano research. u

Hazlett calls the move a “bittersweet denouement” because of his deep affection for Pomona College and its students. But he has a long-running connection to Hawaii, having done many research projects there over the past 40 years, stretching back to the time he was a student.

“In a sense, I’m not really moving to a new landscape or an entirely new social circle,” he says. “It’s a bit of going home, in a way.”

A four-time winner of the Wig Distinguished Professor award, Hazlett chaired Pomona’s Geology Department for nine years. He helped establish the school’s Environmental Analysis Program and became its pioneer coordinator.

Hazlett is moving into a historic house in north Hilo, 30 miles away from the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. His research will likely involve “looking at a prominent fault zone near the summit of the [Kilauea] volcano.”

“That sounds like work, but honest to God, it’s recreation for me,” he says with a laugh.

In addition, Hazlett will be working on two book projects. One is a new edition of a popular textbook, Volcanoes: Global Perspectives, that he co-wrote in 2010. He was also appointed senior editor for a research encyclopedia of environmental science, to be published by Oxford University Press. His focus will be the impact of agriculture on the environment.

“I’m really quite concerned about, and deeply committed to, solving environmental issues that I can impact. I figured this was a great way for me to pursue that mission while moving into retirement.”

Jud Emerick

AFTER TEACHING ART history at Pomona for 42 years, Jud Emerick says he still has as much interest in the field as ever.

“I’ll be doing art history for the foreseeable future,” Emerick writes in an email from Rome, where he’s spending the summer. The current focus of his research, he says, is “how architecture from early Christian and early medieval times in the Euro-Mediterranean world set stages for worship.”

Emerick’s areas of expertise are wide-ranging. As a professor, he taught courses on subjects such as prehistoric and ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Green and Roman art; classical art in the Mediterranean; and painting in Italy during the 14th century.

Emerick and his wife have made Rome “a kind of second home” for the last 46 years. You can sense his passion for the place as he describes attending lectures at landmark sites, eating in local restaurants with friends, and talking art. After all these years, he says, he and his wife “still find that being in Rome is tantamount to being at the center of our art historical world.”

Emerick is also a music buff and says one of his greatest joys is his home music center. (His eclectic musical interests range from American blues to European chamber music to Seattle grunge.) In an age of digital recordings, the self-described audiophile says he hopes to do some online reviewing of new recording formats and equipment.

Honing his language skills is another goal. Emerick says he plans to “learn modern Italian verb tenses (how does one use the subjunctive?), get better at deciphering medieval Latin and even start the study of ancient/medieval Greek.”

Sidney J. Lemelle

AS SIDNEY LEMELLE heads into the future, he’s also revisiting his past. Specifically, Lemelle, a professor of history and black studies, is delving back into his 1986 Ph.D. thesis to expand it into a new manuscript.

His thesis chronicled the history of the gold-mining industry in colonial Tanzania, from 1890 to 1942. Now he’s exploring the post-colonial period, taking the subject up to the present. “I originally looked at gold, for the most part; now I’m looking at gold, diamonds and gemstones,” says Lemelle.

He adds that it’s difficult at times to re-examine his earlier work. “You’re going back to something you’ve written many years ago, and your ideas have changed since then. It takes a little humility.”

Lemelle joined Pomona’s faculty in 1986. A four-time winner of the Wig Distinguished Professor award, he chaired the Intercollegiate Department of Black Studies from 1996 to 1998 and the History Department from 2002 to 2004. His areas of expertise include Africa and the African Diaspora in North America, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Lemelle says he’s also looking forward to teaming up with his son, Salim Lemelle, a 2009 graduate of Pomona College, who is a screenwriter and writing intern at NBC/ Universal. The two plan to collaborate on screenplays.

“I hope we can write historical dramas and that sort of thing,” says the senior Lemelle. “We’ve been tossing ideas back and forth for a long time. Now I’ve got the time where I can actually do it. I’m excited about it, and so is he.”

Laura Mays Hoopes

LAURA MAYS HOOPES is writing a second act to her long career in science: She’s transitioning from biology professor to novelist.

In her retirement, Hoopes plans to put the finishing touches on a novel she penned while earning her MFA at San Diego State University in 2013. The book’s working title is The Secret Life of Fish, and it’s about a girl growing up in North Carolina who develops an interest in science and environmental issues.

“It’s not really autobiographical but it has certain things in common with my life, because I grew up in North Carolina, and I love the beauty of the state,” says Hoopes. “And I know a lot of strange stories about North Carolina history that I was able to weave in.”

Besides exploring the topic of women in science, she tackles issues of ethnicity and Native American identity in the book. There’s also a love story.

Hoopes came to Pomona College in 1993 and served as vice president for academic affairs and dean of the college until 1998, when she moved full time to the faculty. She taught both biology and molecular biology. In 2010 Hoopes wrote a memoir, Breaking Through the Spiral Ceiling: An American Woman Becomes a DNA Scientist.

Hoopes is also working on a nonfiction book. It’s a biography of two major female figures in science: Joan Steitz, a professor at the Yale School of Medicine, and Pomona graduate Jennifer Doudna ’85, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The two entered science about 20 years apart—Joan when there was a lot of discrimination against woman, and Jennifer when pretty much all the doors were open and everyone was just enchanted with her,” says Hoopes. “The whole idea is to look at key stages in their careers. It’s kind of a fun project.”

Ralph Bolton ’61

JUST AS HE DID 53 years ago in the Peace Corps, Ralph Bolton ’61 will be spending his post-Pomona years helping impoverished people in Peru.

The anthropology professor, who began teaching at Pomona in 1972, is president of the Chijnaya Foundation, which aids people in poor, rural communities in southern Peru. Created by Bolton in 2005, the organization designs and builds self-sustaining projects in health, education and economic development. Bolton does the work entirely on a volunteer basis.

“It’s extremely gratifying,” he says. “The people are very grateful. Many of these communities where we work are totally abandoned by any other nonprofit organizations or by the government agencies, and it’s one of the poorest areas of South America.”

His powerful connection to Peru first took root when he was a 22-year-old in the Peace Corps. In the small highland village of Chijnaya, he brought agrarian reform to the farming families, improving their lives dramatically. Hands-on service has always been part of Bolton’s approach as an applied anthropologist, whether he’s helping the destitute or advocating for HIV prevention.

His very popular Human Sexuality class at Pomona pioneered undergraduate discussions on AIDS and HIV when he began teaching it in the late 1980s. In 2010, he was honored with the Franz Boas Award for Exemplary Service to Anthropology, considered the most prestigious award in his profession.

Bolton says he’ll be spending about half the year in Peru, where he’s also working with fellow anthropologists and helping develop anthropology programs in universities.

“I can barely sign in to Facebook without having a Peruvian student or colleague begin to chat with me. So while I regret the loss of my Pomona students, the slack has certainly been taken up by other students of anthropology elsewhere who are very eager to continue to benefit from whatever I have to offer.”

James Likens

JAMES LIKENS SPENT 46 years teaching economics at Pomona. In his retirement, he’ll focus more on family than finance.

“I’m very big into family history. I have more than 17,000 names in my file,” he says. “Genealogy is fun for me perhaps because it’s so different from economics. Economics is driven by numbers and theory; genealogy is driven by documents and stories.”

Likens also served as president and CEO of the Western CUNA (Credit Union National Association) Management School, a three-year program spread over two weeks each July on the Pomona College campus. Since he joined the school in 1972, its annual enrollment has more than tripled from less than 100 to more than 300.

Likens, a winner of the Wig Distinguished Professor award, chaired Pomona’s Economics Department from 1998 to 2001. He also directed the yearlong celebration of Pomona’s Centennial. Likens has long been involved in community service—he has served on nonprofit boards and task forces—and says that will continue. “I will always be involved with service. I don’t know what it will be, but I will do something. It could be a board, or it could be a soup kitchen.”

He also plans to pursue his many interests, which include traveling, golfing, painting and spending time with his family, especially his four granddaughters. In addition, he’ll be working on a memoir.

“I have mixed feelings, of course, about retiring,” says Likens. “I have been at Pomona a long time, and it’s very much a part of my life. On the other hand, I now have the opportunity to do new things, and I look forward to that.”