In November of 1718, the colonial governor of Virginia, Alexander Spotswood, received some disturbing news about an old nemesis.

The pirate known as Blackbeard was fortifying a beachhead in the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The governor there had granted Blackbeard a pardon on the promise of good behavior. But Spotswood smelled a rat. Without telling his neighbors, he personally bankrolled a flotilla of ships to root out the threat he saw to Virginia’s southern flank.

In the ensuing bloody and brutal battle, Blackbeard was killed. Fifteen of his crewmen were tried on piracy charges in Williamsburg, and most went to the gallows. On Spotswood’s orders, Blackbeard’s severed head was perched on a tall pole on a point at the confluence of the Hampton and James rivers, where it stood for years as a warning to would-be buccaneers and marauders.

The clash marked the beginning of the end of what was considered the golden age of piracy, when the real pirates of the Caribbean plundered the Atlantic coast and other points.

But now, the pirates are back.

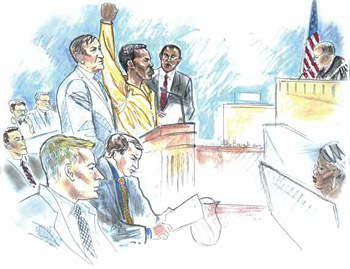

It’s July 2011. Three young men dressed in gray prison garb shuffle into a federal courtroom in Norfolk, Va. They stand accused of hijacking a U.S.-flag vessel a half a world away and summarily executing the four Americans aboard while the military was attempting to negotiate their release. The dead include Jean Hawkins Adam ’66 and her husband Scott, the owners of a 58-foot sloop they called the Quest, and two friends.

Dusting off a statute that dates to the early 19th-century, prosecutors have charged the men with “piracy under the law of nations,” as well as kidnapping, hostage-taking and murder. Eleven of their shipmates have already pleaded guilty to piracy, which carries a mandatory sentence of life in prison. If convicted, the three alleged triggermen could face the death penalty.

The prosecution by the U.S. is a response to an eruption in modern day piracy in the Horn of Africa, where young Somali men have since the mid 2000s largely succeeded at holding the world at bay as they prey upon unarmed merchant ships and other vessels. In the lawlessness of Somalia, piracy has become an organized industry, institutionalized to the point where syndicates sell shares in planned attacks in exchange for a correspondent share of ransoms paid.

Despite heightened international awareness, and patrols from navies across the globe, the scourge has continued, largely unabated. While international law and treaties give countries the right to try pirates they capture in their own domestic courts, they have shown little disposition to do so except in cases that involve their own citizens or ships.

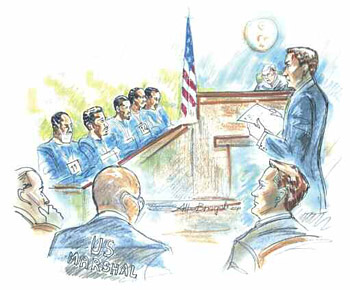

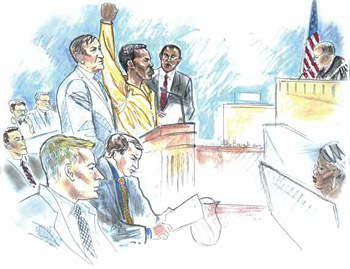

Accused pirates appear before a federal judge. (Courtroom sketches by Alba Bragoli.)

A few have resorted to an old-style sort of summary justice. In a 2010 case, Russian authorities, after apprehending 10 Somali pirates who had seized an oil tanker, decided to cast the suspects adrift in the Indian Ocean, in an inflatable boat. Without navigational equipment, the men likely perished.

But in the vast majority of cases, captured pirates are returned home. Suffering few consequences, they try again and again, a cycle that the United States has until recently helped perpetuate.

As a result, piracy continues to escalate. Attacks on the world’s seas rose 35 percent in the first half of 2011 compared with a year earlier, with Somali pirates accounting for the majority of incidents, according to the London-based International Maritime Bureau. At mid-year, Somali pirates were holding 20 vessels and 420 crew members from around the world, demanding ransoms in the millions, the bureau said.

“There is this race between the pirates and the international community, and progressively that race is being won by the pirates,” said Jack Lang, United Nations Special Adviser on Somali Piracy, in an address to the U.N. Security Council last January.

WHY AND HOW THE QUEST CASE landed here in southeast Virginia, an area rich in pirate lore and naval history (the Civil War battle of the ironclads Monitor and Merrimac was fought in the same waters that Spotswood’s men sailed a century before to go after Blackbeard) is in part an accident of history.

Two U.S. ships that pirates attacked in separate incidents in April 2010 while on patrol in the Gulf of Aden are part of the Norfolk-based Atlantic fleet, the largest naval operation in the world. The pair of attacks, nearly a year before the Quest incident and Jean Adam’s death, helped spur the U.S. government to get back into the business of trying foreign pirates on U.S. soil.

The federal judicial district that includes Norfolk has been the scene of a growing number of international cases in recent years, including a number involving alleged acts of terrorism. Because the district includes the Pentagon, it had jurisdiction over some of the first cases related to the 9/11 attacks. The district is also known as the “rocket docket” because of the speed with which judges move cases along, making it an ideal venue for a government looking to send a signal to the world that it is finally getting serious about piracy.

Last November, prosecutors here won the first piracy conviction in two centuries, against five Somalis in connection with the 2010 attack on the U.S. Navy frigate Nicholas. The last conviction under the federal piracy statute was in 1820, when Thomas Smith was convicted of plundering a Spanish ship from a private armed vessel he commandeered known as the Irresistible.

But the legal cases are not slam dunks. While it is one of the oldest laws on the books, the federal piracy statute is also one of the least used. That has lawyers on both sides plumbing the law books and ancient precedents in an attempt to discern the intent of Congress at a time when an infant U.S. Navy was trying to fend off pirate attacks on U.S. merchant vessels off the Barbary Coast of Africa. The two federal judges here that have had piracy cases have reached different conclusions about the scope of the law, and the issue is now before a federal appeals court.

THE ADAMS—she a dentist, he a film and TV producer in Hollywood—had retired and embarked and on a multi-year trip around the world. They were both highly skilled and experienced sailors, as well as people of faith. They delivered Bibles to residents of remote villages in the Fiji Islands and French Polynesia, among other exotic locales. After more than six years of roaming the globe together, however, they had decided to participate in an organized rally of ships for a leg of their journey from southeast Asia to the Mediterranean, in part for the added security it offered for the trek through the pirate-infested Gulf of Aden.

In January, the Adams joined the new group in Thailand, and took aboard two kindred spirits, Phyllis Macay and Bob Riggle of Seattle, who had been on another boat. Together, they passed through Galle, Sri Lanka and Cochin, India, making a brief refueling stop in Mumbai before heading across the Indian Ocean.

Next stop: Oman. “I have NO idea what will happen in these ports,” Jean had written on a website she had created to chronicle the adventure, “but perhaps we’ll do some local touring.”

They never made it that far.

Organizers for Blue Water Rallies have said the Quest chose to take “an independent route” from Mumbai to Oman, leaving the organized rally on Feb. 15. But family members question that account. Bill Savage ’64, Jean’s first husband, points out that both Jean and Scott were highly skilled sailors.

“There is nothing that they did that was spur-of-the-moment … or not carefully thought through,” he says. “The notion that they would leave the protection of a professionally established routing service to go off on their own … is not credible to the family.”

“It is sad to learn that the family doubt our account,” says Richard Bolt, a Blue Water director, in an email. “We steadfastly maintain our true version of events that the crew on Quest left Mumbai on their own, on a route of their own, which was not recommended by Blue Water Rallies Ltd.” He adds: “There were no members of the company present in Mumbai when this occurred and we can shed no further light on why they took their decisions.” Blue Water announced in March that it was suspending operations, citing the economic downturn and rising piracy in the Indian Ocean.

AROUND THE SAME TIME the Quest departed Mumbai, court documents allege, 19 men pushed off in a skiff from Xaafuun in northern Somalia looking for a merchant ship to snatch. Like many before them, they were young, with little or no schooling, and little or nothing to lose. They were provisioned with bags of beans and rice, barrels of fuel and the tools of the modern pirate’s trade: ladders for boarding larger vessels, a cache of weapons including AK-47 assault rifles and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher.

The onboard leader was a 33-year-old former Somali police officer, Mohamud Hirs Issa Ali, a first-time pirate looking for money to support his two wives, five children and a father in poor health, according to his lawyer, Jon Babineau of Norfolk. The ex-cop had approached a pirate boss in Somalia for a loan, but was persuaded to make a career change. “‘I will make you more money than you can imagine. You will never have to work again,’” Ali was told, Babineau says. “‘You can take care of all of your family. Just make one trip for me.’”

A motivated Ali assembled a crew and set out on his piratical voyage, the first order of business being to find a bigger boat. After two days at sea, he and his mates found one, hijacking a Yemeni fishing trawler.

Six days later, on Feb. 18, a few hundred miles off the coast of Oman, the paths of the Quest and the pirate ship converged. “My guy said he saw the big masts on the horizon and thought it was the mast of a merchant ship,” says Babineau. “They should have turned around and gone the other way. But they didn’t.”

The pirates commandeered the Quest, took their four hostages, and brought aboard their arms and equipment. They allowed the four Yemeni crewmates to take their trawler and leave. The pirates steered the Quest towards northern Somalia.

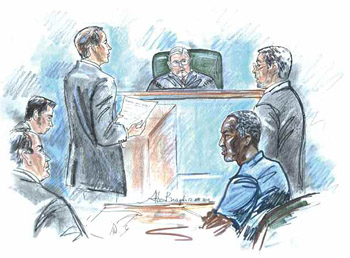

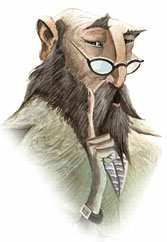

Defendant Mohamed Salid Shibin appears in court.

The first word of the hijacking broke within hours of the siege. Scott Adam had transmitted an emergency SOS to the other boaters in the rally, who apparently alerted nearby merchant ships. The U.S. Navy was soon on the case; news outlets around the world broke the story. A four-day, prime-time drama at sea began. Four warships from the Navy’s Fifth Fleet were re-routed to make contact with the pirates and try to negotiate the release of the hostages. According to court documents, the pirates insisted they would negotiate only when they had returned with the Quest to Somalia.

According to the Navy, on the morning of Feb. 22, a pirate later identified as “Basher” fired a rocket-propelled grenade in the vicinity of the U.S.S. Sterett, the lead ship trailing the Quest. The Navy said the move was unprovoked and a surprise, since two of the pirates had boarded the Sterett to negotiate. An eruption of small-arms fire from the yacht followed the rocket-propelled grenade. In response, a party of 15 Navy SEALs raided the Quest. Two pirates were killed. Two were found already dead, killed by fellow pirates as they attempted to shield the hostages from gunfire. Jean and Scott Adam and their two new friends from Seattle were found mortally wounded. Fifteen suspects were captured.

While not disputing that the pirates fired first, Babineau and other lawyers for the defendants contend that the Navy took steps that compounded the situation. They say the Navy refused to allow the two pirates who had boarded the Sterett to return to the Quest, which angered their cohorts. They also contend that the Navy SEALs were already in the water approaching the Quest as part of a middle-of-the-night rescue attempt when the pirates saw them and began firing.

“The Navy took them on the ship and said, ‘Now you are ours. We are not letting you guys go back,’” Babineau says. “Unfortunately, that started to escalate things.” A spokesman for the U.S. Naval Forces Central Command declined comment.

The suspects were jailed in a brig aboard the aircraft carrier Enterprise, another Norfolk-based vessel, where they were interrogated by FBI agents and housed for two weeks while a decision was made where to send them and what to charge them with. One of the suspects, a juvenile, was returned to his family.

The bodies of Jean, Scott, Phyllis and Bob were brought to the Enterprise, where an honor guard watched over their caskets for three days, according to Savage. A memorial ceremony was held on the deck of the carrier attended by several thousand sailors and officers in full dress before the bodies were flown back to the United States. The 14 prisoners were flown on a U.S. Air Force plane to Norfolk. The next day, a federal grand jury indicted them on piracy charges.

FOR CENTURIES, PIRATES were dealt with not in the courts, but at sea, summarily executed or cut adrift in a boat.

“Pirates were considered beyond the pale. They were outlaws. You could basically string them up … and nobody was going to ask any questions,” says Lindley Butler, a historian and author of the book, Pirates, Privateers, and Rebel Raiders of the Carolina Coast. They were universally condemned as “enemies of mankind,” attacking outside the territorial waters of states, without regard to the nationality of ships or crews, he says.

Blackbeard himself got something of a raw deal, Butler says, because the preemptive strike Gov. Spotswood launched was illegal. While he cultivated a murderous reputation, there is no evidence the infamous pirate ever actually murdered anyone, at least outside of combat, says Butler, who has participated in dives that have located artifacts from Blackbeard’s flagship, the Queen Anne’s Revenge, off the Carolina coast.

But due process for pirates also has a surprisingly long history.

In colonial America, accused pirates and necessary witnesses had to be shipped back to Britain for trial in admiralty court, as was the case with Captain William Kidd (who had made a fortune plundering French shipping as a privateer for the King of England until he got sideways with some of his colonial investors).

That changed in 1700 when Parliament authorized trials abroad before seven-member “commissions.” The statute provided explicit due process guarantees: commissioners had to swear an oath of impartiality, and defendants had explicit rights, including the right to produce witnesses. Under the law, any conviction as a pirate required either the testimony of two witnesses or a confession.

In 1819, relying on language in the Constitution that gave it the power “to define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas,” Congress adopted a version of the British statute. The law authorized “public armed vessels” to seize “piratical vessels” and permitted trials of those who committed “the crime of piracy, as defined by the law of nations,” on the high seas, if they are “brought into or found in the United States.” This language remains essentially intact in the U.S. criminal code to this day.

Two centuries later, however, the scope of the law remains unsettled, in part because there have been so few piracy cases over the years. Before 2009, the last pirate trial in the U.S. involved the captain and 11 crew members of the Confederate vessel Savannah who were captured after attacking a Union warship in 1861 during the Civil War. The jury deadlocked.

Two judges here in Norfolk have come out differently on exactly what constitutes piracy in separate cases involving groups of Somali pirates that fired on the Nicholas and the U.S.S. Ashland, while the ships were patrolling the Indian Ocean in April 2010.

U.S. District Court Judge Raymond A. Jackson threw out the piracy charges against the group that fired on the Ashland, an amphibious landing ship, ruling that the definition of piracy in the federal law must be limited to the definition understood at the time the law was enacted—in 1819—when piracy was limited to robbery on the high seas. Since the attack on the Ashland was unsuccessful—no robbery took place and the pirate ship was destroyed after the Ashland returned fire—the judge dismissed the piracy charge.

But Judge Mark S. Davis of the same federal district court reached the opposite conclusion in the Nicholas case. He held that the original law was written in broad enough terms that Congress must have intended that the meaning of piracy would evolve over the years. Piracy today, he ruled, unquestionably covers attacks on the high seas that do not include the taking of hostages or goods.

Davis cited a 1958 convention adopted by the United Nations Law of the Sea that incorporates a sweeping definition of piracy to include “any illegal acts of violence, detention or any act of depredation.” Davis ruled that the attack on the Nicholas could be prosecuted as piracy. The five defendants were subsequently convicted in a trial last November, and sentenced to life in prison.

Federal public defenders representing some of the accused pirates have criticized Davis’s reasoning. By referring in the original statute to piracy “under the law of nations,” their argument goes, Congress meant to include only crimes that were rooted in natural law, and were thus immutable.

The idea that law comes from a transcendent authority has long been in disrepute. But the intent of the writers and thinkers of that era is still relevant in understanding what Congress had in mind when it came to piracy, the lawyers contend. They have cited such authorities as Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language and the works of 17th-century theorist and philosopher Hugo Grotius as proof that piracy had a limited meaning.

Other legal experts say both law and common sense militate against defining piracy narrowly. “A legitimate Somali fisherman might carry one AK-47 for protection,” says David Glazier, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, and a specialist in international law. “But a legitimate fisherman does not carry boarding ladders, rocket-propelled grenade launchers and a dozen AK-47s.” Any vessel found in international waters with that kind of gear should be presumed a pirate vessel, and anyone on board should be presumed a pirate, Glazier says.

A federal appeals court in Richmond heard arguments on the Nicholas case this fall. A defeat would be a blow to the U.S. anti-piracy effort, although it would not be expected to affect cases such as the Quest where the perpetrators succeeded in actually commandeering a vessel and the people on board.

TRUE TO THE COURT’S “rocket docket” reputation, the government secures agreements with 11 of the defendants in the Quest case to plead guilty to piracy and hostage-taking, barely two months after they land in the United States.

The price is a steep one: the deals mean each faces a mandatory life sentence, but they also avoid the possibility of being tried on murder-related charges that could bring the death penalty.

The interrogations have already yielded one central figure, a man named Mohammad Saaili Shibin, an onshore operator based in Somalia and experienced negotiator in piracy cases, whose specialty is divining the ransom value of hostages on the Internet.

The government alleges that, the day before they were killed, Shibin was doing research on the Americans to identify family members he could contact about a ransom. He was also to have been the point man in negotiations with the Navy if the hostages had made it back to Somalia alive. Shibin was arrested in Somalia in early April, following a joint U.S. military-FBI investigation.

Besides piracy charges related to the taking of the Quest, Shibin is also charged with acting as a negotiator in the case of a German vessel that was pirated in May 2010, and with extracting from the owners of the ship a ransom that was dropped from an aircraft into the ocean for the pirates to retrieve. The charges related to the German hijacking are among the first the U.S. has charged against a foreigner for piracy where neither the hostages nor the vessel had connections to the United States.

On July 20, the three accused triggermen in the Quest case are arraigned on murder charges before a magistrate judge in a Norfolk courtroom that is filled with lawyers, the bulk of whom represent the defendants. A superseding indictment alleges that the three “intentionally shot and killed” the four Americans “without provocation.” Their 11 co-conspirators have agreed to testify against their fellow pirates in exchange for leniency.

Mohamud Hirs Issa Ali in federal court.

“We have 11 cooperating witnesses in this case,” Benjamin L. Hatch, the lead prosecutor, says at the hearing. One of them is the former Somali cop who convinced prosecutors that he was ousted as the leader of the group before the firing began and did not participate in the shootings. Hatch also reveals that the Navy has video of the events surrounding the hostage ordeal that could be introduced into evidence at a trial.

The Quest itself, the government says in a court filing, has returned to the United States after being sailed to Djibouti by the Navy after the attack. It is to remain in the custody of the Navy, a crime scene made available for defense lawyers to inspect at the Naval Base in Norfolk, until the end of September. After that, arrangements are to be made to return the yacht to the Adams’ family.

With little or no ability to read and write, the defendants have the indictments read to them by translators. Polite, clean-shaven and quietly defiant, they each profess their innocence.

“This is not a crime I have committed,” Shani Nurani Shiekh Abrar, at 29, the oldest of the three, says through a translator. “It is just an allegation. I have never killed anyone.” Abrar is also charged with firing a warning shot over the head of Scott Adam, and ordering him, through another pirate who spoke some English, to tell the Navy that if they came closer the Americans would be killed.

The prosecutors agree to put off further proceedings until April. Among other things, the government needs to go through a process at the Justice Department to decide whether it will ask for the death penalty if the men are convicted. The chances are considered good that such a request will be approved; the prosecution has recently added a lawyer to its team who won the last death penalty verdict in Virginia, in a murder-for-hire plot that resulted in the death of a Navy officer.

The defense lawyers—who will have the right to appear before Justice to argue against death—say they need time to prepare. Some have started contacting private investigators with contacts in Somalia who may be able to find out mitigating information about their clients they could use to argue against death. But for now the lawyers are operating with a blank slate.

“This case is so much different than anything we are used to facing,” says Stephen Hudgins, a lawyer for Abrar.

In his office in Alexandria, Va., Neil H. MacBride, the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, says he hopes such prosecutions will send a message about the resolve the U.S. now has for dealing with piracy, as well as provide a degree of closure to families of the victims.

“It is our hope that stiff sentences will get the attention of would-be pirates, and stop the attacks,” he says in an interview. “Piracy is a dangerous, deadly business. My kids love Pirates of the Caribbean, but that swashbuckling, romanticized notion of Hollywood movies bears no resemblance to the cases that we are seeing today.”

SIDEBAR:

OFF ON ANOTHER ADVENTURE: a brief biography of Jean Hawkins Adam ’66

The day before she died at the hands of Somali pirates, Jean Hawkins Adam ’66 wrote a short letter to her two grown sons, Brad and Drew. On a sheet of yellow legal paper, Jean told them she didn’t know how the situation was going to turn out, but she wanted them to know that she and Scott loved each other, had had wonderful lives and were doing exactly what they wanted to be doing, according to their father and Jean’s first husband, Bill Savage ’64.

Having the presence of mind to pen that succinct letter was very much in character for Jean, who was always focused and had a tremendous ability to get things done, says Savage.

Born in 1944 and raised primarily in Indio, Calif., Jean made it through Pomona through work and scholarships. Savage remembers the time a classmate asked Jean how she was able to take part in all the social events while everyone else had their noses to the grindstone. “She very blithely looked up and said ‘I learned how to study and pay attention in class,’” recalls Savage.

The pair wed in 1965. While Savage finished his M.B.A. at The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Jean took a position with an anthropologist studying early childhood cranial bone development, which sparked her interest in dentistry. The couple returned to California, and Jean went on to dental school at UCLA, establishing a practice in Santa Monica. She became involved in the California Dental Association, American Dental Association and the California State Board of Dental Examiners, for which she served as president for two terms.

Jean was widely admired and well liked, says Savage, adding that the one “exception would be people uncomfortable with women in positions of power and influence.” No matter: “She would just plow right through them like a steamroller,” recalls Savage. “That was Jean. Enormous focus. Enormous ability to execute.”

Even after they divorced in 1991, Jean and her ex-husband remained friends and spent holidays together with the boys.

Through the years, Jean also remained close with a group of four other Pomona classmates, who called themselves the Sagechicks. Her decisive, outspoken side was balanced by her “inclusive and caring and very giving” nature, says Jackie Showalter ’66, who recalls that Jean would provide free dental work to low-income kids.

Jean had taken up piano and she would host “talent nights” at her home to give friends a chance to perform. She had a distinctly ebullient laugh. “You knew it was Jean” when you heard it, says Showalter.

There was depth as well. “A key thing for my memory of Jean in college, religion was very important to her,” says Showalter. “She would do her devotional every evening. I remember her sitting on her bed and doing her Bible reading.”

When Jean met Scott Adam in the mid-’90s, both were already avid boaters. After they wed, they took their journeys to more distant waters. Jean got her captain’s license and their 58-foot sloop, Quest, logged more than 200,000 miles as the couple sailed the globe for adventure and to deliver Bibles to remote places. Jean was constantly updating the Quest website (still at www.svquest.com) and emailing updates to friends. “You would open it with anticipation,” says Margaret Haberland Noce ’66.

Noce also recalls Jean’s enthusiasm when she joined the couple on excursions to places such as Catalina and Santa Cruz islands. “She would say ‘OK, we’re off on another adventure,’’’ says Noce. “And we were. You always learned something when you were with Jean.” —Mark Kendall