Our story begins with a long-ago knock on a door on a balmy June evening. The door is in France, at the apartment of a very young Kimball Jones, just a year out of Pomona where he was known as a nice guy who could often be found playing the grand piano in the lounge at Walker Hall or performing with his small jazz group for school dances.

But at this moment, Jones is simply an American in Paris. He is living the continental life thanks to the largesse of the French government, which awarded him a scholarship for this year following his 1960 college graduation. In return, three days a week he teaches conversational English at a lycée in suburban Paris. Much of the rest of his time he spends sitting on the iconic green chairs in the Jardin des Tuileries outside the Louvre. There, during an unusually warm February, he reads the entire works of Camus and Gide in French. In the evenings he goes to the cafés to drink good beer and better wine. He is living the life.

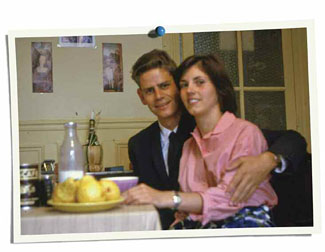

As befitting a young man living in the most romantic city in the world, he has fallen in love with a Swiss woman, Margrith. On this particular night in June, it is 10 o’clock. Jones and Margrith are engaged in the most ordinary of activities—cleaning the kitchen in his apartment from top to bottom. They have no way of imagining that, in a moment, the knock on the door will come, drawing Jones into a cascade of events that will change the balance of power in Africa.

Kimball Jones ’60 and Margrith in Paris.

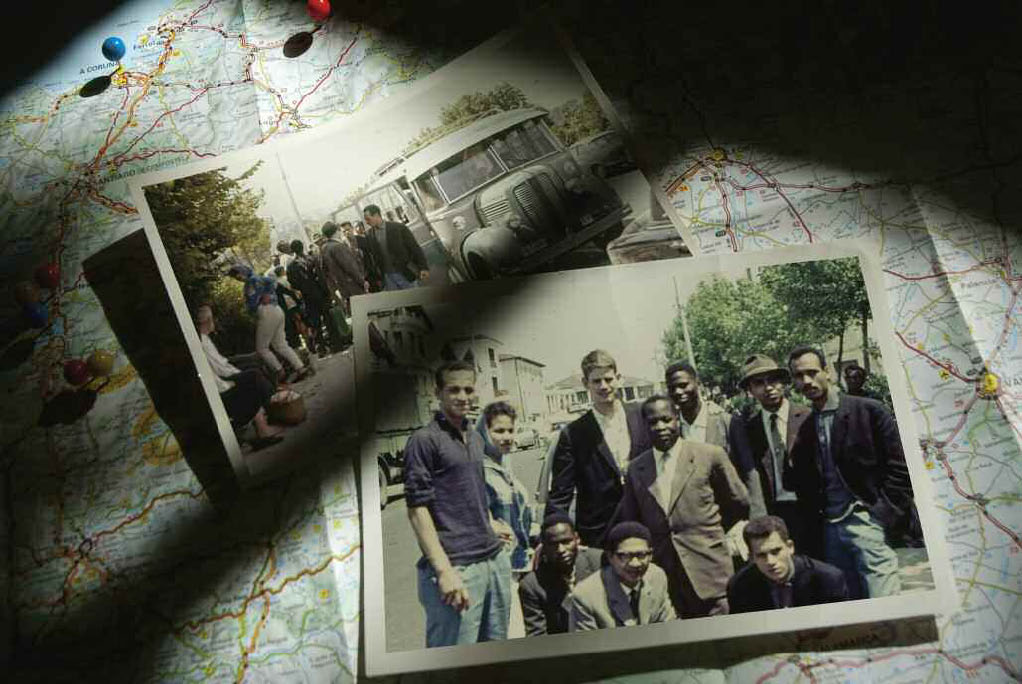

Fifty years later, Jones is recounting this tale, sitting at the table of his sunny New York apartment with newspaper clippings and 8-by-10 black-and-white photographs spread out in front of him. Margrith brings in the worn brown leather diary he carried with him those many years ago and in which he kept an account of his remarkable experience that began on this one early-summer evening in Paris.

Down on the street in the Place d’Italie is a fellow by the name of Bill Nottingham whom Jones has met only once before, in an interview at the French refugee organization Cimade. Nottingham doesn’t know Jones’ exact address, so he stops people on the street, asking if they know where the tall American lives. Eventually, someone waves him in the direction of Jones’ apartment, where he interrupts their cleaning that night—along with their lives for a time.

Nottingham can’t discuss the urgent matter that has brought him there in front of Margrith, so he asks Jones to come down and talk to him in his car. Much later that night, Jones describes their conversation in his journal, crowding the words onto the pocket-sized pages:

I am almost hesitating to write this down, as it is very important and must be kept secret. Bill asked me if I could leave Paris tomorrow for a week. The story is as follows: There has been much trouble in Angola (Africa) recently. Out of 16 Methodist missionaries, 13 are dead or missing. There are many Angolese students in Lisbon, Portugal. The Portuguese government has taken their passports, immobilizing them. There is a good chance that a follow-up of the Angolese affair could occur in Lisbon, directed against these students. In fact, the possibility of a mass slaughter is not an exaggeration. These students are in hot water!

Before the month is over, Jones will end up in his own hot water, in the confines of a Spanish prison. But he’s not thinking about the possibility. Perhaps when Nottingham asks him to drive a car across Spain and back to clandestinely transport these fugitive students, he might have been wise to mull it over for a moment or two. But he is swept up in the drama and intrigue of it all. He answers in less time than it would have taken him to pick out a shirt to wear. He doesn’t think of himself as a hero. He doesn’t see himself playing a role in a historic moment. Truth be told, he sees it as an adventure, a great story to tell in years to come.

Clinging To Empire

Portugal had been a presence along the coast of Africa since the late 15th century as the first European nation to establish settlements and trading posts. The European colonization of Africa’s interior would begin in earnest at the grandiose behest of Belgium’s King Leopold II, who sat down with other European leaders in 1884 and blithely divvied up the continent not unlike the way the modern-day game of Risk begins. But while one after another African colony claimed its independence in the aftermath of World War II, Portugal, under the dictatorship of António Salazar, had held tightly to its holdings in Africa, including Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Principe.

Long-simmering tensions in Angola, on the western coast of Africa, had come to a head six months earlier when peasants who worked in the cotton fields protested their low wages and deplorable working conditions. The protest turned into a revolt. Portuguese traders were attacked. A month later in retaliation, the Portuguese military bombed villages, killing many thousands of the indigenous population.

The African students believed to be at risk in Portugal were among the first to complete a university education there. Salazar, fearing the political and intellectual leadership they might contribute to their homelands, had not only detained them by taking away their papers, but also had them tailed by his secret police, the PIDE (pronounced pee-day).

The leaders of the Methodist Board of Missions and World Council of Churches (WCC) had decided to secure false papers for these students and smuggle as many of them as they could across Spain—which had its own dictator—and into France where they would be given political asylum. Because of Cimade’s experience with this kind of endeavor, the WCC asked that organization to plan and carry out what would later become known as “the Fuga” (meaning escape or flight in Portuguese).

Jones will leave Paris in 24 hours. The first thing in the morning he procures his international driver’s license. It happens to be the final week of the school where he teaches, but under Nottingham’s advisement, Jones simply doesn’t show up. Later he is too embarrassed to go back and explain. For all the head of the lycée ever knew, he had fallen off the face of the earth.

To Margrith he confides only that he is going on a secret mission for Cimade. If anyone asks, he says, tell them I’ve gone off to Geneva for a conference. That cover story is so convincing that when he tells Mrs. Hauser, for whom he has been doing some house painting, she pulls out a Swiss watch that wasn’t working and asks him to get it repaired while he is there. He pockets it, not knowing what to do with it. Like so many other things, he’ll figure it out later.

Paris, France — June 14, 1961

The “big adventure,” as Jones calls it in his diary, gets underway that evening. Jones and two of the other drivers meet up for a relaxing dinner in the Latin Quarter. Dick Wyborg and Dave Pomeroy are students from Union Theological Seminary in New York who just happened to visit Cimade the day before and were pounced on by Bill Nottingham when he found out they had driver’s licenses and some free time.

That night, they all board an overnight train from Paris to Bayonne, a town north of the waistline border between France and Spain. Almost immediately, they get behind schedule. There are two trains to Bayonne that night—the express they are supposed to be on that arrives around 6 a.m. and another one that takes a more leisurely route, arriving at 11. When they disembark some five hours late, they find the gentleman from Hertz International who has waited for them the entire time.

During the next several days, Jones’ journal seems like something of a travelogue, as the drivers meander their way along the French coast. (Each of the four have their own rental cars, but they travel the route in tandem.) They are looking for a border crossing into Spain with few checkpoints, but not so small that they will stand out when they return with the African students. They settle on Hendaye, a resort town on France’s Atlantic coast. Then they begin their trek following secondary roads primarily along the Spanish coastline. The rendezvous near the Spain-Portugal border is 600 long and bumpy miles away. Cimade has encouraged them to look the part of tourists by staying at good hotels and eating fine meals. (In Spain, they can get an excellent meal for the equivalent of $2.) Jones, relishing the opportunity provided, has no trouble complying. He has a new 35 mm camera and enjoys taking photographs of the picturesque towns and sweeping coastline views. He buys some souvenirs as well—a leather bag for himself and a purse for Margrith—marveling at the inexpensive prices.

Towns along this route later become a litany to them—a tick for another leg of an endless journey. But on that first passage, when his heart isn’t pounding from moments like a near head-on with a truck on one of the hairpin curves through the mountains and his bottom isn’t aching from the long stretches of tremendous ruts on unpaved roads, Jones marvels at the sights, including the elaborately ornate cathedral in the city of Santiago, shown to them by a young Spanish hitchhiker. It doesn’t occur to them until later that picking up hitchhikers—they even picked up soldiers along the road—could compromise them. “They say that ignorance is bliss,” says Jones these many years later, as he speculates that his political naïveté may have kept him from a nervousness that might have given him away.

No matter how long the day behind the wheel, Jones still takes time every night to record observations:

Though today was a fatiguing day filled with much tension from trying to drive “as fast as possible,” it was also an enjoyable day—for we drove through some beautiful countryside. The people along the road are also very interesting. There were many places where we wanted to stop and take pictures or to watch something that was going on, but we couldn’t take the time. On one spot we saw a traditional funeral procession—women in black robes and veils, men with the casket on their shoulders, marching to the slow chimes of the little church.

After three days of traveling, and a final push of 60 miles, they arrive at their destination of Pontevedra, a town north of the Portuguese border. The next day their covert work will begin in earnest.

Spain-Portugal Border — June 18, 1961

While Jones and his fellow drivers have enjoyed something of a sojourn as they make that first run across Spain, the Portugal side of the operation has been fraught with tension and intrigue. Cimade officials Jacques Beaumont and Chuck Harper are coordinating that part of the escape, slipping African students out of Portugal, hopefully before the PIDE catches on. In one case, they spirit two young men away from a bar right under the noses of plainclothes PIDE, who have been tailing them for days. The men innocently get up to use the restroom where they jump out a small window, and are whisked away while the PIDE enjoy their wine.

Nineteen Africans are brought to the banks of the Minho River, which marks part of the northern border between Portugal and Spain. There, a notorious coffee smuggler with land on both sides of the border and family connections to Portuguese and Spanish customs police runs his well-oiled operation. The Fuga crew gave him the nickname “Edward G.” because of his gruff, no-nonsense manner, which reminded them of the gangsters portrayed by American actor, Edward G. Robinson. Beaumont and Harper wait with the students in the tall brush above the river until the first light when they slip and slide their way down to the water and clamber into a small rowboat three or four at a time.

The river has a treacherous current. At any time, it could have carried them around a bend and into view of the border patrol on either side. But the crossings turn out to be blessedly uneventful. Up above the steep riverbank on the Spanish side is a windowless barn where they will wait in stifling heat and in complete silence until the arranged pick-up at mid-day. “During that Spanish siesta time when ordinary Galicians, guards, dogs, every living thing and time stopped,” Harper wrote in a recollection, “four spacious automobiles, one after another, came to a stop in front of the barn door facing the dirt road, with their American drivers.”

Jones and Pomeroy get their first taste of the cloak-and-dagger maneuver when they pull up alongside the barn where the fugitives are hidden and five figures dart out, eyes blinking as they adjust from the radical darkness to full sunlight, faces filled with trepidation. As soon as they jump into the car, Jones gives them the papers with their false identities that have been supplied by the Senegalese and Congolese embassies in Paris. They are to immediately memorize the information in case they are stopped somewhere along the way.

The tension in the car is palpable. Jones drives many hours with barely a word uttered. Even had there been, he wouldn’t have understood much. The students, for the most part, speak Portuguese, Spanish and their native African languages. A few know a little French. They don’t plan to stop much as they hasten back towards San Sebastian, 600 miles away near the French border. But late that afternoon, the right rear axle slips out of joint on Jones’ car. It is a Sunday. They are in the mountains. Two of the students who know Spanish hitch a ride into the next town and, miracle of miracles, find mechanics—two brothers— who know how to fix Chevys. But to everyone’s consternation, when the students arrive back with the mechanics, they are accompanied by two guards ominously armed with machine guns— Franco’s men, says Jones in his diary, referring to Spain’s autocratic head of state, General Francisco Franco. To make matters worse, a student has left one of his documents where it can be seen through the window—and where it is duly noticed. “Oh,” says the mechanic off-handedly. “These are Angolese students from Portugal. You never know what these Americans will do for a thrill.” The comment is enough to raise the hairs on the back of everyone’s necks. But the policemen say nothing. They don’t even ask to see passports.

In the end, Jones saw this delay as a bonding moment. The mechanics fix the car enough to get it to town where they have to work on it for a few more hours. Meanwhile, they lead the group to a dirty stucco building across from the garage where they can get some dinner while they wait:

There we encountered “Pepita” who served us a wonderful meal of some wild bird. We had great time talking and laughing, kidding Pepita. For the first time, everyone really seemed to relax—and it was at this point that I really developed a warm feeling toward these fellows.

Pepita’s place was like something out of the middle ages, yet we wouldn’t have found Maxim’s to be half so enjoyable. Outside her place was a little “place” where three pigs were running around loose, oinking. A little old lady was sitting there watching over them.

This incident proved to be more a blessing than a hindrance for it served to loosen up everyone. We wouldn’t have missed this evening in Mondoñedo for anything.

Shortly before midnight, they get back on the road. In one of the sweeter moments, the students sing Angolese freedom songs. One in particular catches Jones’ fancy—the haunting Muxima, which is the name of an Angolan town. It means heart in Kimbundu, one of the native languages of Angola. Fifty years later, Jones can still sing it.

Northern Spain — June 19, 1961

The drive becomes a punishing exercise for an exhausted Jones, who nonetheless plows on through the night. In the mountains outside of Oviedo in northern Spain, they run into thick fog. By then, Jones is almost dreaming as he drives, he is so tired. On one curve he doesn’t leave enough room. When he slams on the brakes, the car spins around, nearly smashing into the side of the mountain. That is a wake-up call, so to speak. As soon as there is a place to stop, he pulls over and sleeps for an hour-and-a-half.

By now, dawn is almost breaking. The nap doesn’t do much for his fatigue, though. He stops to get some coffee, but he is still dangerously groggy. Further down the road, he starts seeing things. It is the only time in his life, he says now, that he ever hallucinated. Giant, animated rabbits hop across the road in front of him. He can’t think clearly. When he stops the car and gets out for a breath of fresh air, he can hardly stand up. He feels drunk. But still he continues the marathon. One hour fades indistinguishably into the next, until they finally arrive in San Sebastian. By then, another day has passed. It is 5 o’clock in the evening.

The next day the group approaches the Spanish border crossing. Bill Nottingham has to meet with the commissariat of police and explains that the group has been on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela and is now returning to France. The Spanish official is nervous and suspicious, sensing that things are not what they seem. However, he allows them to cross.

Jubilation! The Africans will board the next train to Paris. As for the four chauffeurs, they return to their hotel for a celebratory meal and a good night’s rest before their own return to Paris the next day.

But that is not to be. While they are still enjoying their dinner, Nottingham is called to the phone. It is Jacques Beaumont in Portugal. He speaks in code, saying that the “picnic” went so well he wants them to return the next day. They are going to do it again.

This is not what Jones has expected. By now, the tedium of driving has replaced some, although not all, of the romance of the adventure. But he is more familiar with the roads, and has the greater wisdom to stop and sleep in the car for longer than a catnap when he gets tired. Still, it’s no picnic for him.

Spain-France Border — June 30, 1961

Two more trips across Spain and back deliver 41 additional Africans from the troubles in Portugal to the Spanish side of the border crossing with France. Because the original group had gotten over the border into France with no real trouble, Nottingham decides to expedite matters and take this much larger group of “pilgrims” across en masse. This time, though, things don’t go as hoped.

First of all, everyone, including, apparently, the commissariat, is celebrating at a huge festival. The streets are filled with music, parades and dancing. The anxious group sits at a café, watching the revelry and biding their time until Nottingham comes back with permission to cross the border. They wait through most of the day.

When the commissariat returns, it is a different official than the first one. The new commissariat wants to talk with each student individually, so he has them arrested and taken to the governor’s palace in San Sebastian. The students are searched and interrogated. Everyone manages to hide the papers from Cimade allowing them to seek political asylum in France—with the exception of one individual. That’s all it takes. The guard who is questioning this unfortunate soul runs out into the hallway, waving the paper and calling loudly to his comrades. Soon the students are all handcuffed and everyone, including Nottingham and Jones, are put in military vehicles and taken to the prison in San Sebastian. Amazingly, despite the exhausting reality of the past three weeks, Jones savors even this moment, which he records later:

I’ll never forget that ride, under armed guard, across San Sebastian in the back of a Land Rover.

My attitude was perhaps a bit of a stupid one, for I was carried away (as was Dave) by the romantic conception of spending a night in a foreign prison.

… Our cell had bars on the windows and door, a small crucifix on one wall. There was a room with several washbasins on the right-hand side of the door, and a room with several “Turkish-style” toilets on the left-handed side. Looking out the door you could see an enclosure which stretched around a square, with a long hall extending from the other side, and at the commencement of this hall was a statue of Mary, lit by candles. Our mattresses were very smelly (of sweat and dirt, probably hadn’t been washed for months!).

He manages to hang onto the feeling he is on an adventure even when dinner is served—a half loaf of thick bread with smelly cheese and unidentifiable brown glop. It is only when other prisoners come in the next morning with instructions to assemble 44 beds that Jones began to appreciate the serious ramifications of the circumstances in which he found himself.

The night before, the students had sung the Angolese freedom songs until well after midnight. But now spirits are so low that many of them simply lie back down and go to sleep to try to keep from worrying about what will come next.

For Jones, it is a moment of reckoning. Margrith and the plans he was making for the future loom large. Now he feels pinned in place while everyone else in his life is free to move forward. His three weeks on the road seem less the romantic adventure, and more the serious matter that it has always been. Would he have chosen to get involved had he known it would land him in prison in a foreign country? Probably, but that is little consolation at this moment.

And then, miracle of miracles, they are awakened late in the afternoon by a guard telling them to get their things and get out. They are leaving. Don’t ask questions. Don’t look back. Just get out of here, get out of Spain, and don’t come back.

Over the Years

Kimball Jones never has. He never returned as a tourist to the lovely coastal towns that had enchanted him. But several years after the operation—after Jones had married Margrith, attended Union Theological Seminary and become pastor of a church in Antwerp, Belgium—he was visited by a minister with ties to Africa. Melvin Blake, who oversaw the Methodist Church’s missionary work in Angola, had been the one to get the ball rolling on the Fuga. Blake let Jones in on the secret of how they were all sprung from prison, as reported to him in a debriefing from the CIA. When Portugal’s Salazar learned that 60 of his political de- tainees had slipped out of the country without the PIDE noticing, and that 41 of them were now being held in a Spanish prison, he demanded them returned immediately. Spain’s ruler, Francisco Franco, took offense at the request. Thus it was that after a few exchanges between the two countries, Franco settled it all by opening the prison gates and letting them all go.

Jones’ brief career as a secret operative was over—and not a moment too soon.

Over the years, Jones wondered what had become of the students. He got his answer last summer when, out of the blue, he was invited to a 50th reunion of the Fuga as guests of Pedro Pires, the president of Cape Verde, who had been in the Fuga.

Some of those students settled in France, others in Switzerland and Russia. They were physicians and engineers and, as Salazar had worried, political leaders who played roles in the liberation of Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde and other nations. The reunion, Jones says, was a veritable Who’s Who of Portuguese- speaking Africa. Among the 60 African students that Cimade helped to rescue were three who would go on to be presidents of their newly independent countries, four prime ministers, five ministers of defense, a minister of health and a Methodist bishop.

Jones himself has spent close to 40 years as a pastoral psychotherapist with the Psychotherapy and Spirituality Institute in New York City. On the side, he is a gifted jazz pianist who has performed with his group at Birdland and other jazz clubs in New York. But one of his most recent gigs may stand out as the highlight of his career. At a nightclub one of the evenings in Praia, the capital of Cape Verde, he took a turn as a guest musician, playing an original jazz composition, which he renamed, in honor of the occasion, “Bossa de Fuga”—the music of the flight.

1) Cape Verde

2) Guinea-Bissau

3) Sao Tome and Principe

4) Angola

5) Mozambique

Flight into History

Last summer, Kimball Jones ’60 found himself on a plane heading for Africa—and 50 years into the past—after President Pedro Pires of the island nation of Cape Verde called a reunion of people who took part of the 1961 Fuga. The theme for the event was “The Flight toward the Fight” (“A Fuga Rumo à Luta”) in recognition of how many of the African students who escaped went on to be leaders in their countries’ struggles for independence from colonial rule.

On the flight from Lisbon to Praia, capital of Cape Verde, Jones was reunited with Joaquim Chissano, who was part of the Fuga and served as president of Mozambique from 1986 to 2005. Chissano, in first class, learned of Jones’ presence and came back to find him.

“Margrith and I were napping,” Jones remembers, “when Chissano suddenly took my hands in his and said, ‘Kim, Kim, do you realize what we achieved together, my friend?’” Reminded of the Angolese freedom songs they had sung together during the drive, Chissano began to sing a favorite, called “Muxima,” and Jones joined in. The photo above was taken right after they finished singing.

In all, three of the six original rescuers—Jones, Chuck Harper and Bill Nottingham—along with 16 of the original 60 escapees were able to attend. Among those were Pascoal Mocumbi, a medical doctor who was prime minister of Mozambique from 1994 to 2004; Manuel Boal, who led the World Health Organization in Africa; along with three others who served as prime minister of Angola. Along with sharing memories, participants reported to the group on the political development of their nations since the Fuga. The conference was well covered by African news media and drew film crews from Angola and Portugal, each working on documentaries about the Fuga.

Running back Luke Sweeney ’13 led all of NCAA Division III football in rushing this season, averaging 177.4 yards per game for Pomona-Pitzer and setting both single-game and single-season school records along the way. Featured in the Los Angeles Times and USA Today for his standout season, Sweeney’s path to Sagehen sports stardom began half a continent away in the suburbs of Tulsa.

Running back Luke Sweeney ’13 led all of NCAA Division III football in rushing this season, averaging 177.4 yards per game for Pomona-Pitzer and setting both single-game and single-season school records along the way. Featured in the Los Angeles Times and USA Today for his standout season, Sweeney’s path to Sagehen sports stardom began half a continent away in the suburbs of Tulsa.

I hadn’t wanted to go to racing school. I’d rather not go fast, and I’m not the physically adventurous type. The only boundaries I like to push are how many books I can read in a week. But I’d had the idea to write a mystery series set in the car racing world after working in corporate marketing for a racing series sponsor. The fact that I’d never written a mystery—that I’d written fiction for the first time in my life only a few months prior—hadn’t stopped me from pitching my nascent idea to a published author. She encouraged me, with one caveat: My sleuth, who I’d seen as a woman in corporate marketing, had to be the racecar driver.

I hadn’t wanted to go to racing school. I’d rather not go fast, and I’m not the physically adventurous type. The only boundaries I like to push are how many books I can read in a week. But I’d had the idea to write a mystery series set in the car racing world after working in corporate marketing for a racing series sponsor. The fact that I’d never written a mystery—that I’d written fiction for the first time in my life only a few months prior—hadn’t stopped me from pitching my nascent idea to a published author. She encouraged me, with one caveat: My sleuth, who I’d seen as a woman in corporate marketing, had to be the racecar driver. Sooner than I wanted it to, the moment of truth arrived: my first solo laps. I sat waiting in the rumbling car, sweating and terrified, hoping my shaking legs would be able to work the clutch and throttle. I wondered again why I was doing this and why I hadn’t chosen something more normal and less violent to write about besides racing. Tea parties and embroidery, perhaps. And then they waved me out.

Sooner than I wanted it to, the moment of truth arrived: my first solo laps. I sat waiting in the rumbling car, sweating and terrified, hoping my shaking legs would be able to work the clutch and throttle. I wondered again why I was doing this and why I hadn’t chosen something more normal and less violent to write about besides racing. Tea parties and embroidery, perhaps. And then they waved me out. Since she was working for the company putting up the cash, Kaehler got inside access at the track, riding in top-of-the-line Porsches and meeting “everyone and their uncle.” She became fascinated with auto racing: the money, the violence, the rock-star drivers.

Since she was working for the company putting up the cash, Kaehler got inside access at the track, riding in top-of-the-line Porsches and meeting “everyone and their uncle.” She became fascinated with auto racing: the money, the violence, the rock-star drivers. “Nowhere in the public discourse did we see a reflection of the funny, independent and opinionated Muslim women we knew,” says Maznavi, who, with co-editor Ayesha Mattu, thought an anthology could help fill the void. “We decided to compile our faith community’s love stories as a celebration of our identity and heritage, and a way of amplifying our diverse voices, practice and perspectives.”

“Nowhere in the public discourse did we see a reflection of the funny, independent and opinionated Muslim women we knew,” says Maznavi, who, with co-editor Ayesha Mattu, thought an anthology could help fill the void. “We decided to compile our faith community’s love stories as a celebration of our identity and heritage, and a way of amplifying our diverse voices, practice and perspectives.” We knew it was coming. For years, we have happened across little items in other colleges’ alumni magazines about students playing Harry Potter-inspired Quidditch matches. Competitors in “Muggle Quidditch” move the ball down the field while holding broomsticks between their legs in a gravity-bound version of the aerial competitions at Hogwarts. In the absence of real magic, the winged and evasive Golden Snitch (above) is replaced by a tennis ball stuffed in a sock and carried in the shorts of a player known as the snitch runner. The Muggle [that is, non-magic] version started at Middlebury in 2005. Now, via the Student Digester, we learn there is a recently-formed team for students of The Claremont Colleges. They call themselves the Dirigible Plums, and they will compete against UCLA, Oxy and others at the Western Cup tournament in March.

We knew it was coming. For years, we have happened across little items in other colleges’ alumni magazines about students playing Harry Potter-inspired Quidditch matches. Competitors in “Muggle Quidditch” move the ball down the field while holding broomsticks between their legs in a gravity-bound version of the aerial competitions at Hogwarts. In the absence of real magic, the winged and evasive Golden Snitch (above) is replaced by a tennis ball stuffed in a sock and carried in the shorts of a player known as the snitch runner. The Muggle [that is, non-magic] version started at Middlebury in 2005. Now, via the Student Digester, we learn there is a recently-formed team for students of The Claremont Colleges. They call themselves the Dirigible Plums, and they will compete against UCLA, Oxy and others at the Western Cup tournament in March. Since then, Paul has carved out an illustrious career in choral conducting and, this month, will return to the Pomona campus as clinician of the 2012

Since then, Paul has carved out an illustrious career in choral conducting and, this month, will return to the Pomona campus as clinician of the 2012