SAGEHENS ARE COMING together in record numbers—both in person and online—to learn, mingle and make a difference.

Alumni Weekend 2015

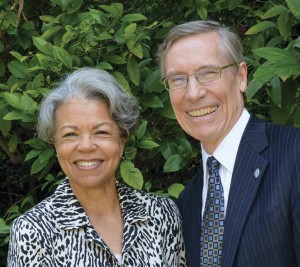

This year’s Alumni Weekend brought together more than 1,600 alumni and guests for a weekend of for a weekend of fun, celebration and hundreds of campus activities, including performances, open houses and lectures. Highlights included the Daring Minds Speakers Series, featuring Blaisdell Award winners James Turrell ’65, Bill Keller ’70 and Mary Schmich ’75, the first-ever 47th Reunion, held by the Class of 1968 (see story on page 47), and a Claremont in Entertainment and Media panel featuring Richard Chamberlain ’56. At the gathering in Little Bridges preceding the Parade of Classes, Alumni Distinguished Service Award winners Jeanne Buckley ’65 P’92 and Stan Hales ’64 were recognized, class volunteers were celebrated and over $3 million in reunion class gifts were announced. (For more photos, see Last Word, page 64.)

Winter Break Parties

In January, Sagehens around the world flocked together in growing numbers to take part in a favorite community tradition. Winter Break Parties brought nearly 1,000 Pomona alumni, parents, students and friends together in 15 cities from Kansas City to Shanghai for laughter and libations, stories and Sagehen spirit. Interested in hosting a Winter Break Party in your city this season? Contact Kara Everin in the Office of Alumni & Parent Engagement at kara.everin@pomona.edu for more information.

Daring Minds Events

Pomona’s yearlong celebration to wrap up Campaign Pomona: Daring Minds kicked off last spring with a series of events designed to help Sagehens learn, mingle and make a difference. Highlights this spring included:

- Daring Minds Lectures: On campus (including nationally noted poet Professor Claudia Rankine in April) and across the nation (including the East Coast lecture series in March, featuring Professors Amanda Hollis-Brusky and Char Miller).

- 4/7: A Celebration of Sagehen Impact: This social media-driven effort celebrated the good work and good will of a community full of “everyday Daring Minds.” More than 150 civic-minded Sagehens and friends posted about their good deeds, and the good deeds of Pomona friends, while hundreds more chirped their encouragement through “likes” and comments. Community members also pledged and performed service as part of the celebration, including 16 Seattle Sagehens who came together on a rainy Saturday to plant 447 trees at a local nature preserve. It’s not too early to start planning: What will you do to make a difference by next 4/7?

- Senior Send-Off: For 47 hours leading up to Class Day and Commencement, hundreds of alumni, parents, faculty, staff, students and friends rallied for the College’s first Senior Send-Off, a mini-campaign to honor the graduating Class of 2015 and support Pomona education for all current students. Nearly 500 donors gave more than $80,000, and dozens more alumni, students, faculty and friends took to social media and the campaign web site to offer their “sage advice” to graduates as they make their life-changing transition.

- Daring Minds Videos: Watch for your invitation to tune in for a series of Daring Minds videos to be made available starting in September. On the playlist are Professor Claudia Rankine and alumni James Turrell ’65, Bill Keller ’70 and Mary Schmich ’75.

Career Networking Events

Alumni volunteers across the country organized and hosted a series of career networking events this spring and summer. From Los Angeles to Chicago and New York, more than 100 members of the Pomona community came together to connect with fellow Sagehens and share industry-specific and general career stories and advice, and the program continues to grow! Interested in hosting a career networking event in your region? Contact the Alumni and Parent Engagement team at alumni@pomona.edu.

To make sure you hear about exciting events and opportunities yet to come, update your contact information by emailing alumni@pomona.edu or calling 1-888-SAGEHEN.

Travel/Study

Hawaiian Seascapes

(Big Island to Molokai)

With Professor Emeritus Rick Hazlett

Dec. 5–12, 2015

Board the Safari Explorer for a seven-day cruise from the Big Island of Hawaii to Molokai, with stops on West Maui and the “private island” of Lanai. Enjoy dramatic volcanic backdrops and marine life sightings. (NOTE: At publication, there was only one cabin left on this cruise.)

From Angles to Angels:

The Christianization of Barbarian England

With History Professor Ken Wolf

May 18–29, 2016

The eighth in a series of alumni walking trips with a medieval theme, this is the first involving the United Kingdom. Its purpose is to appreciate the fascinating history (captured by the Venerable Bede) of the conversion of the barbarian conquerors of England, starring the Irish and Roman missionaries. In Scotland, you will visit Kilmartin, Dumbarton and Loch Lomond; in England, Lindisfarne, Hadrian’s Wall and Durham Cathedral.

Inner Reaches of Alaska

June 4–11, 2016

Join Pitzer Professor of Environmental Analysis Paul Faulstich on an “un-cruise” through the stunning Inner Reaches Coves of Alaska. Aboard a small vessel serving 74 passengers, adventurers will travel from Juneau to Ketchikan, encountering stunning glacial landscapes, old-growth forests and incredible wildlife.

For more information, contact the Office of Alumni and Parent Engagement at

1-888-SAGEHEN or alumni@pomona.edu.

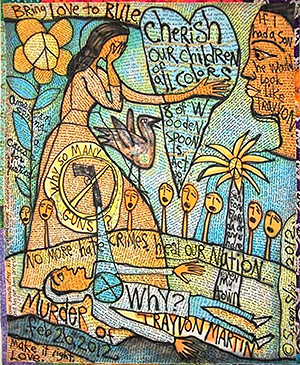

March 6, at Pomona College and Scripps College, invites viewers to contemplate the visceral, spiritual, emotional and political dimensions of diaspora.

March 6, at Pomona College and Scripps College, invites viewers to contemplate the visceral, spiritual, emotional and political dimensions of diaspora. Florida, will be on display at Pomona College, beginning Feb. 23. The quilts come from the Fiber Artists of Hope Network and reveal reactions to Martin’s death in 2012 and hopes for a better America.

Florida, will be on display at Pomona College, beginning Feb. 23. The quilts come from the Fiber Artists of Hope Network and reveal reactions to Martin’s death in 2012 and hopes for a better America.

The number of gallons of water the College expects to save each year due to new pH controllers installed on its 10 water-cooling towers. Purchased last March, the new controllers reduce the number of water replacement cycles in building air conditioning systems.

The number of gallons of water the College expects to save each year due to new pH controllers installed on its 10 water-cooling towers. Purchased last March, the new controllers reduce the number of water replacement cycles in building air conditioning systems. The number of pounds of used appliances, furnishings, books and other items (including 100+ couches) saved from the landfill last May in the College’s Clean Sweep, which picks up items left behind in residence halls for resale the next fall. This year’s sale raised more than $9,500 for sustainability programs.

The number of pounds of used appliances, furnishings, books and other items (including 100+ couches) saved from the landfill last May in the College’s Clean Sweep, which picks up items left behind in residence halls for resale the next fall. This year’s sale raised more than $9,500 for sustainability programs. The number of new low-flow faucets and showerheads installed as part of the College’s Drought Action Plan. The College also reduced irrigation to landscaped areas by at least 20%, timed watering schedules for night-time and prohibited washing of outside walkways.

The number of new low-flow faucets and showerheads installed as part of the College’s Drought Action Plan. The College also reduced irrigation to landscaped areas by at least 20%, timed watering schedules for night-time and prohibited washing of outside walkways. The number of bicycles available to students last year through the College’s Green Bikes program, in which students check out bikes for the entire semester and learn how to repair and maintain them.

The number of bicycles available to students last year through the College’s Green Bikes program, in which students check out bikes for the entire semester and learn how to repair and maintain them. The percentage of produce served in Pomona’s dining halls last year that came from local sources

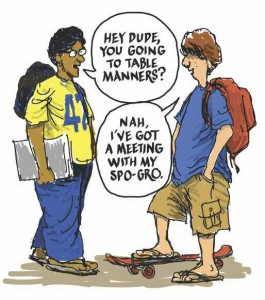

The percentage of produce served in Pomona’s dining halls last year that came from local sources 2) Laughing Matters (Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Jose Cartagena-Calderón) grew out of the professor’s research into the meaning and value of humor in Hispanic literature and art.

2) Laughing Matters (Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures Jose Cartagena-Calderón) grew out of the professor’s research into the meaning and value of humor in Hispanic literature and art.