Members of the Alumni Association Board include: (from left, front row) Emma Fullem ’14, Jared Mathis ’94, LJ Kwak ’05, Onetta Brooks ’74,Cathie Moon Brown ’53 P’75, Kyle Hill ’09, (second row) Jahan Boulden PZ’07, Jon Siegel ’84, Guy Lohman ’71, (third row) Anne Bachman Thacher ’75 P’07, Diane Ung ’85, Mac Barnett ’04, Nico Kass ’16, Maggie Lemons ’17 (intern), Mary Raymond, (fourth row) Lisa Phelps ’79 P’12, (fifth row) Roger Reinke ’51 P’80 GP’14, Emma Marshall ’14, Jordan Pedraza ’09, Brenda Barnett ’92, Matt Thompson ’96, Professor Lisa Beckett, (sixth row) Ward Heneveld ’64 P’92, Craig Arteaga-Johnson ’96 and Taziwa Chanaiwa ’95 P’17. Not pictured are: Conor O’Rourke ’03 and Peggy Olson ’61.

The Alumni Association Board held its first meeting of the year, led by Alumni Association President Onetta Brooks ’74, on October 4. President Oxtoby shared an informal “State of the College” and members were joined by parent and student guests for the following committee meetings:

- Athletic Affinity (alumni co-chair Jared Mathis ’94)

- Alumni Career Services (alumni co-chair Matt Thompson ’96)

- Young Alumni Engagement (alumni co-chair Emma Fullem ’14)

- Giving/Service Days (alumni co-chair Lisa Phelps ’79 P’12)

- Current Matters of Concern (alumni co-chair Cathie Brown ’53 P’75)

To nominate someone for the Alumni Association Board, email alumni@pomona.edu.

Winter Break Parties

Celebrate the new year with a Pomona College Winter Break Party, coming to a city near you January 2–15, 2016! Held while students are home for winter break, this Pomona College tradition is one of the best ways for alumni to connect with students in their hometowns and to meet fellow Sagehens living nearby.

2016 Winter Break Parties are currently being planned for Boston, Chicago, Kansas City (Missouri), Los Angeles, Menlo Park, New York City, Philadelphia, Phoenix, Portland, San Francisco, Seattle and Washington, D.C.

Don’t miss out—check out our listings at pomona.edu/alumnievents for details and updates about the Winter Break Party nearest you.

4/7 Celebration of Impact

Civic-minded Sagehens: Make sure you are part of Pomona’s second Celebration of Sagehen Impact, scheduled for April 7 (yes, 4/7), 2016. Last year, more than 150 Pomona students and alumni flooded the College’s Alumni Facebook group and Instagram feeds with pledges, shout-outs and stories about the many ways Sagehens are “bearing our added riches” on campus, in our neighborhoods and around the globe. Organize with fellow Sagehens or find your own ways to contribute your time, talent or treasure to the causes that mean most to you. Our community will be ready to celebrate your good work on April 7.

Budenholzer Heads List for Hall of Fame

Mike Budenholzer ’92 with Mens’ Basketball Coach Charles Katsiaficas.

National Basketball Association Coach of the Year Mike Budenholzer ’92 and former Athletic Director Curt Tong were among the honorees when the Pomona-Pitzer Hall of Fame inducted six new members this fall. Also honored during the 58th annual induction ceremony were Scott Coleman PO ’05 (soccer); Joy Haviland PZ ’03 (water polo, swimming); Kevin Hickey PO ’99 (baseball); Lucia Schmit PO ’03 (water polo, swimming). Budenholzer was inducted as an honorary member (basketball) and Tong was honored for his years of distinguished service as athletic director.

Want to keep up with our sports teams and engage with the Athletics community? Follow @Sagehens on Twitter and like “Pomona-Pitzer Sagehens” on Facebook.

Ladd Named Inspirational Young Alumna

Jessica Ladd ’08

Jessica Ladd ’08 has been selected as the recipient of the 2015 Inspirational Young Alumni Award. Ladd, who was featured in the summer 2015 issue of PCM, is the founder and CEO of Sexual Health Innovations (SHI), a non-profit dedicated to creating technology that advances sexual health and wellbeing in the United States. At SHI, she spearheaded the creation of the STD partner notification website So They Can Know, the STD test result delivery system Private Results, and the college sexual assault reporting system Callisto.

Before founding Sexual Health Innovations, Ladd worked in the White House Office of National AIDS Policy, as a Public Policy Associate at The AIDS Institute, and as a sexual health educator and researcher for a variety of organizations. She also co-founded The Social Innovation Lab in Baltimore and a chapter of FemSex at Pomona College. Ladd has also recently been recognized as a Fearless Changemaker by the Case Foundation, an Emerging Innovator by Ashoka and American Express, and as the Civic Hacker of the Year by Baltimore Innovation Week.

Video Corner

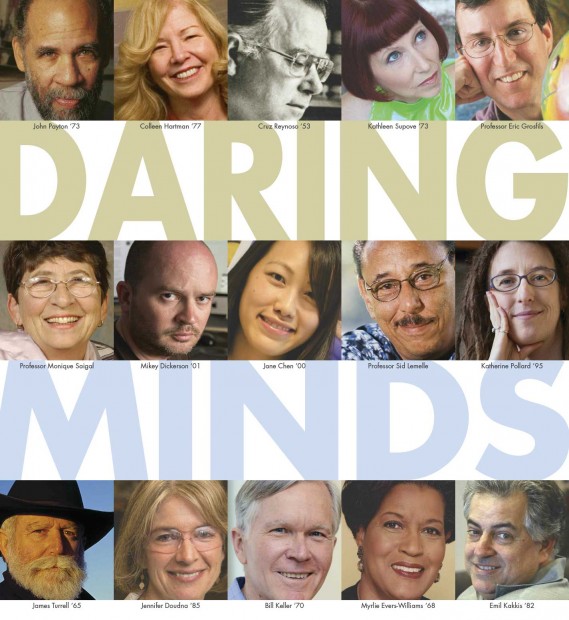

Daring Minds Talks

Tune in to a series of thought-provoking online lectures withmembers of our alumni community, including James Turrell ’65, EdKrupp ’66, Mary Schmich ’75, Bill Keller ’70 and Gabe London ’00. To find the Daring Minds playlist, and for more inspirational speakers and enriching stories from campus, visit youtube.com/pomonacollege and click “Playlists.”

Travel/Study

From Angles to Angels: The Christianization of Barbarian England

With History Professor Ken Wolf

May 18–29, 2016

The eighth in a series of alumni walking trips with a medieval theme, this is the first involving the United Kingdom. Its purpose is to appreciate the fascinating history (captured by the Venerable Bede) of the conversion of the barbarian conquerors of England, starring the Irish and Roman missionaries. In Scotland, you will visit Kilmartin, Dumbarton and Loch Lomond; in England, Lindisfarne, Hadrian’s Wall and Durham Cathedral.

For more information, contact the Office of Alumni and Parent Engagement at 1-888-SAGEHEN or alumni@pomona.edu.

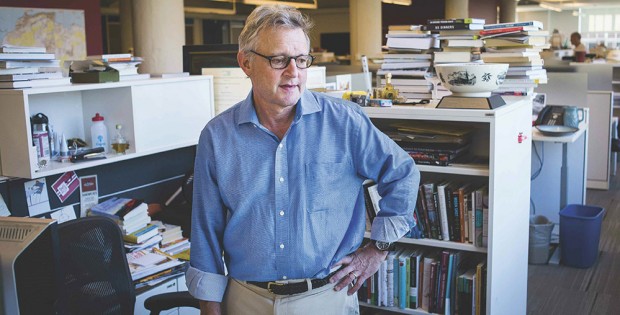

Joe Palca’s cubicle in NPR’s Washington, D.C., headquarters is strewn with bicycle gear from his daily commute, assorted piles of books about science, and random objects: a can of mackerel, a leaf-shaped bottle of maple syrup. From this cluttered perch, the longtime science correspondent has the power to shape what becomes news. If Joe Palca ’74 decides a story is worth putting on the air, roughly a million listeners hear it. And if he misses a story, well, some of those listeners may never hear about it.

Joe Palca’s cubicle in NPR’s Washington, D.C., headquarters is strewn with bicycle gear from his daily commute, assorted piles of books about science, and random objects: a can of mackerel, a leaf-shaped bottle of maple syrup. From this cluttered perch, the longtime science correspondent has the power to shape what becomes news. If Joe Palca ’74 decides a story is worth putting on the air, roughly a million listeners hear it. And if he misses a story, well, some of those listeners may never hear about it. Of course, not all subjects have such inherent drama. Still, Palca says, scientists are not the cold-blooded, calculating creatures they are often presumed to be. “I’m sick of the caricature, of the white lab coat. The lab coat says ‘I’m an expert, not a person.’”

Of course, not all subjects have such inherent drama. Still, Palca says, scientists are not the cold-blooded, calculating creatures they are often presumed to be. “I’m sick of the caricature, of the white lab coat. The lab coat says ‘I’m an expert, not a person.’”

If you are ever offered a tour of the new Millikan Laboratory and Andrew Science Hall with David Haley as your guide, take it. A 21-year veteran of physics departments, he has an enthusiasm for his subject that is nonstop and infectious. Completely at ease in the corridors of Millikan’s new underground laboratory, he misses no opportunity to point out the fascinating creations of Pomona students and faculty.

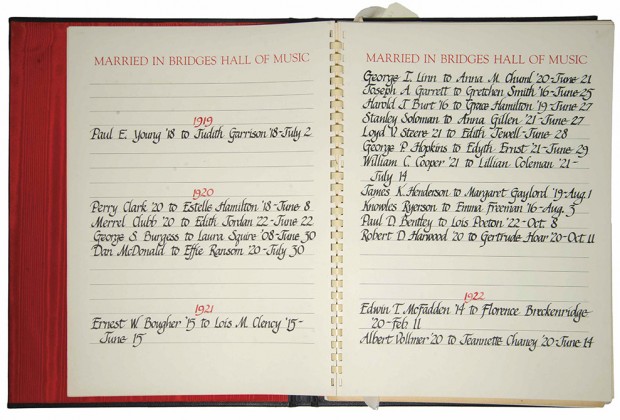

If you are ever offered a tour of the new Millikan Laboratory and Andrew Science Hall with David Haley as your guide, take it. A 21-year veteran of physics departments, he has an enthusiasm for his subject that is nonstop and infectious. Completely at ease in the corridors of Millikan’s new underground laboratory, he misses no opportunity to point out the fascinating creations of Pomona students and faculty. As Bridges Hall of Music celebrates its centennial, many Pomona alumni look back fondly at the place where they said “I do.” The Little Bridges Wedding Register is a historical record of marriages that took place in the building, starting with Howry Warner 1912 and Mary Roof 1912, married June 1, 1916. Compiled in the early 1970s, the register was maintained and updated through 1992 and includes the names of 453 couples.

As Bridges Hall of Music celebrates its centennial, many Pomona alumni look back fondly at the place where they said “I do.” The Little Bridges Wedding Register is a historical record of marriages that took place in the building, starting with Howry Warner 1912 and Mary Roof 1912, married June 1, 1916. Compiled in the early 1970s, the register was maintained and updated through 1992 and includes the names of 453 couples.

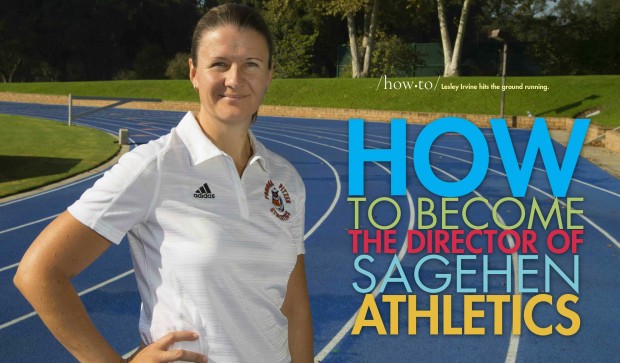

There’s nothing particularly surprising in the fact that Pomona-Pitzer’s new athletic director has hit the ground running. Lesley Irvine has been moving fast ever since she was a child—first as a multi-sport athlete, then as a high-profile coach and finally as an athletic administrator. At Pomona, she has assumed a newly created full-time position as chair of Pomona’s Physical Education Department and director of the joint athletic program of Pomona and Pitzer colleges.

There’s nothing particularly surprising in the fact that Pomona-Pitzer’s new athletic director has hit the ground running. Lesley Irvine has been moving fast ever since she was a child—first as a multi-sport athlete, then as a high-profile coach and finally as an athletic administrator. At Pomona, she has assumed a newly created full-time position as chair of Pomona’s Physical Education Department and director of the joint athletic program of Pomona and Pitzer colleges. Grow up in Corby, a steel town in central England where most people are of Scottish descent and speak with a Scottish brogue. Develop into an active child, always sporting a scraped knee. Get involved in athletics with the encouragement of your dad, an avid soccer player, coach and fan.

Grow up in Corby, a steel town in central England where most people are of Scottish descent and speak with a Scottish brogue. Develop into an active child, always sporting a scraped knee. Get involved in athletics with the encouragement of your dad, an avid soccer player, coach and fan. Join a track and field club at the age of 9 and, since you excel in a range of athletic events, specialize in the heptathlon. In high school, find yourself playing almost every sport, from basketball to volleyball to soccer. Discover the game of field hockey and fall in love with it.

Join a track and field club at the age of 9 and, since you excel in a range of athletic events, specialize in the heptathlon. In high school, find yourself playing almost every sport, from basketball to volleyball to soccer. Discover the game of field hockey and fall in love with it. Accept an invitation to play on the English junior national field hockey team at the age of 16, while also competing internationally in the heptathlon. Play for England in a victory over Scotland in the Six Nations field hockey tournament and have to explain to your teammates why your dad, a proud Scot, is rooting against you.

Accept an invitation to play on the English junior national field hockey team at the age of 16, while also competing internationally in the heptathlon. Play for England in a victory over Scotland in the Six Nations field hockey tournament and have to explain to your teammates why your dad, a proud Scot, is rooting against you. Become the first member of your family to go to college, playing field hockey at prestigious Loughborough University. While there, win five national championships. During your second year, teach tennis at a summer camp in Maine (though you’ve never touched a tennis racquet before) and find yourself at home in American sports culture.

Become the first member of your family to go to college, playing field hockey at prestigious Loughborough University. While there, win five national championships. During your second year, teach tennis at a summer camp in Maine (though you’ve never touched a tennis racquet before) and find yourself at home in American sports culture. After graduating, come back to the U.S. for graduate school, attending the University of Iowa and playing competitive field hockey for one more year, scoring the only goal in a 1–0 victory over Stanford University in your first trip out West and leading your team to a Final Four appearance. Earn your master’s degree in health, leisure and sports studies.

After graduating, come back to the U.S. for graduate school, attending the University of Iowa and playing competitive field hockey for one more year, scoring the only goal in a 1–0 victory over Stanford University in your first trip out West and leading your team to a Final Four appearance. Earn your master’s degree in health, leisure and sports studies. Return to Stanford as assistant women’s field hockey coach. Discover that you love working with committed student athletes who love sports as much as you do. After two years, succeed the retiring head coach and spend eight years at the helm of Stanford’s elite program, guiding them to three straight NorPac championships.

Return to Stanford as assistant women’s field hockey coach. Discover that you love working with committed student athletes who love sports as much as you do. After two years, succeed the retiring head coach and spend eight years at the helm of Stanford’s elite program, guiding them to three straight NorPac championships. Leave Stanford to enter sports administration, spending five years at Bowling Green State University and rising to the rank of senior associate athletic director. Decide the job at Pomona-Pitzer is a perfect match for your abilities and your desire to help build something special for talented and motivated student-athletes while promoting wellness for a whole community

Leave Stanford to enter sports administration, spending five years at Bowling Green State University and rising to the rank of senior associate athletic director. Decide the job at Pomona-Pitzer is a perfect match for your abilities and your desire to help build something special for talented and motivated student-athletes while promoting wellness for a whole community