Most of the people gathered around the card tables at the Senior Center in Longmont, Colo., this morning seem to be my age or older—in their 60s or 70s. They sit three or four to a table and peek at their cards, as I do at mine.

Most of the people gathered around the card tables at the Senior Center in Longmont, Colo., this morning seem to be my age or older—in their 60s or 70s. They sit three or four to a table and peek at their cards, as I do at mine.

Unlike most card games, GoWish gives each player a full deck—cards bearing no diamonds or spades, no aces or deuces. Just words. Words like: “To be mentally aware.” And “Not to be connected to machines.” And “To be at peace with God.”

The object here isn’t winning—it’s understanding. By organizing our cards into numbered priorities, we’re all seeking to come to grips with the nitty-gritty of our own mortality—that is, to decide how we would prefer to die.

As I shuffle through my cards and grapple with my own priorities (Do I want to be free from pain more than I want the chance to see my close friends one last time? Should I rank having my financial affairs in order above having a doctor I trust?), my host, Peggy Arnold ’65 wanders from table to table, asking probing questions and offering nuggets of information about the world of modern death. Just starting the process of talking about the subject, she says, is therapeutic—taking us back to a day when death was a visible part of life.

“Death in our culture has become a medical event, not a personal experience,” she says. “It used to be that children would run in and out of the parlor when the body was lying there. Or people grew up on farms, where life and death were always present.” Modern death, she says, is often hidden away behind hospital curtains, and most people have no clue what awaits them there.

At my table, one person picks as her top priority “To be free from anxiety.” Another chooses “To have an advocate who knows my values and priorities.” I settle on “To have my family with me.”

In each case, it soon becomes clear that there are personal experiences behind the choice. The person who wants to be free from anxiety explains that her mother spent weeks before her death in a terrible state of fear. The person who hopes for an advocate worries about having no one she can trust. It only occurs to me afterward that my own choice might have something to do with the fact that both my parents died suddenly, without a chance to say goodbye.

“What’s really interesting about that game,” Arnold says, “is what happens when people have a discussion about why they chose what they chose. Really, it’s a values clarification game.”

Taking Back Dying

For Arnold, the program coordinator for Longmont United Hospital’s AgeWell program, this game, and the reflections and conversations it prompts, are also part of a larger movement—a grass-roots crusade that has been spreading across the country for the past few years. The goal: to reclaim death from the medical establishment and empower people to make choices about how they wish to spend their final days.

“To me, what’s exciting is that people are starting to take back their own death and dying process,” she says. “Look at everything that goes on around birth—all the joy and the care, the respect and the dignity that goes on. But on the other end of the conveyor belt, this hasn’t been happening.”

Today, medical technology can prolong life almost indefinitely, but as Arnold points out, in too many cases that has simply prolonged suffering and turned the end of life into a horror show. “Most people—there are always exceptions, but most people—are not going to want to go out of this life hooked to beeping machines, with tubes everywhere,” she says.

Like the Advanced Directives class she teaches at the Senior Center, this game of GoWish is intended to help participants think clearly about their options while there’s still time. Arnold likes to quote Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ellen Goodman, the founder of The Conversation Project, who said: “It’s always too soon, until it’s too late.”

Since 2010, The Conversation Project has been focusing on encouraging people to have a conversation with their loved ones about their end-of-life wishes. That, however, is only one of the visible prongs of this burgeoning movement. Another is the Death Cafés, which sprang up in the United Kingdom, also in 2010, and have now spread across the United States, offering people a forum for freewheeling discussions of death and dying over cookies or a slice of cake. Then there’s the Green Burial movement, which seeks to reclaim the long-lost right of natural burial, without embalming or caskets or concrete vaults to inhibit the natural recycling process. And at the heart of it all, there’s an increasing number of activist physicians like Dr. Angelo Volandes, author of The Conversation, and Dr. Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal, who are seeking to change the ethos of end-of-life care by pulling back the curtain on hospital death and challenging both their fellow doctors and the public to look at the subject differently.

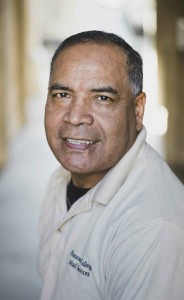

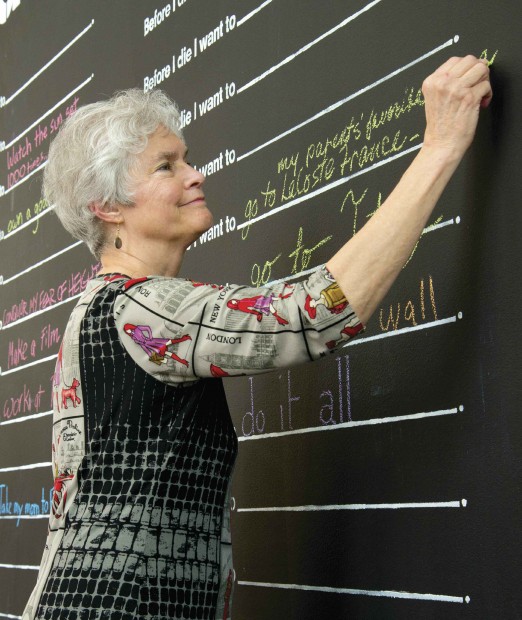

Peggy Arnold ’65 adds her wish to the “Before I Die” Wall at the Art Museum of the University of Colorado, Boulder.

In the area around Longmont and Boulder, Arnold is at the center of a small but determined community of end-of-life reformers whom she dubs, with affection and “M*A*S*H”-style humor, “the Deathies.” There’s Kim Mooney, an experienced end-of-life counselor and certified thanatologist (death scholar) who recently started her own company, called Practically Dying. There’s Bart Windrum, who, following the disastrous hospital experiences of his two dying parents, was moved to write Notes from the Waiting Room, a guide book for families of the terminally ill. There’s retired emergency room physician Jean Abbott, who is urging her fellow doctors to get over their squeamishness about removing patients from life-prolonging equipment when the outcome is no longer in doubt.

What the Deathies all have in common is that they’re passionate about returning control over the end of life to the dying and their families.

One Death

For her part, Arnold says death has always seemed an integral part of her life. Her mother’s father died two months before she was born, and she suspects that her mother’s grief may have affected her in the womb. One of her first playgrounds in her hometown of Oberlin, Ohio, was a cemetery where she played among the tombstones of runaway slaves. Then there was her grandfather’s suicide by walking in front of a train here in Claremont. “I could go on and on with all these experiences of death,” she says. “So it’s really no surprise that it’s been a theme for me. Maybe not THE theme, but it’s definitely been part of the story.”

Having worked as a hospice volunteer before taking her current job 15 years ago, she says the part of her work that relates to “the death trade” just evolved naturally. “You could call it ‘unbidden,’” she says. “It just appeared, and I was the one who was asked to do it.”

First she was designated as the hospital representative to a short-lived organization called the Front Range End of Life, which focused on creating resources for the terminally ill. Then the hospital decided to do a video about planning for the end of life, and guess who got the job? Then they needed someone to teach a class on advanced directives… “It’s like the underground of aspen groves,” she says. “Their root systems go on for acres and keep shooting up new stems. The time for this had come, and I happened to be in the middle of the grove.”

Then, five years ago, her focus on death and dying took a turn for the personal. An old friend, Mogens Baungaard Thomsen—a Danish exchange student in her high school who had become a vascular surgeon in Sweden—revealed that he was living with a death sentence—kidney cancer that had metastasized to his lungs.

“We just started Skyping a lot and had the most fascinating conversations,” Arnold says. “At some point, I said, ‘Mo, I’d love to record what you’re saying. I think it is so wise.’ He was a physician. He was a widower. Now he was facing his own end.”

So they made a video together about his experience of dying. “He talked about all the adventures he’d had in his life, like being with headhunters in New Guinea, and how everything he did was just a new adventure,” she says. “Sometimes it was scary, but he knew that was part of who he was. He loved all those adventures. And so, he was looking at death as the next adventure.”

Peggy Arnold ’65 at her desk with a photo of Mogens Thomsen and his granddaughter.

At the time, Thomsen didn’t expect to live long enough to see his new grandchild, but he outlived his own prognosis. “There’s a picture of them together,” Arnold says, pointing to a photo pinned above her desk of Thomsen holding his granddaughter. “And he actually lived almost two years longer.”

During that time, they made two more videos together. The first, prompted by Thomsen’s terrible experiences with the Swedish healthcare system, is aimed at his fellow doctors, giving them heart-felt advice on how to relate to people who are dying.

The second, made shortly before his death, is less philosophical, more practical and more emotionally raw—what he wants for his last meal (a cheeseburger or maybe fish and chips); what music he would like to hear on his deathbed (a piece by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy that he listened to with his wife while she was dying); what he wants on his epitaph (“I don’t want one”).

The exchanges between Thomsen and Arnold sound at times like an interview, at times like old friends chatting, at times like therapy. “Although I’ve seen so many people die, I still don’t know what goes on at the end,” Thomsen reflects at one point. “As long as I’m aware of what’s going on, I would probably want to cling to my relatives and have them with me, but that’s a very egoistic way of thinking. I don’t think it’s a pleasure for them to see me die.”

“You could ask,” Arnold gently suggests. “It may not be a pleasure, but it may be important.”

“You’re right,” Thomsen says. “I hadn’t even thought of asking. Thank you.”

Four months later, when Thomsen finally reached what he called his “expiration date,” both of his sons were at his side.

“As it turned out, he had a medical emergency, went to the hospital, and though he would never have wanted to die there, that’s exactly what happened,” Arnold recalls. “And it was probably the best thing, as it turned out, because a really good friend who was a doctor was able to be there to make sure everything was going to happen the way Mo would want it. And it meant that his two sons could actually be there.”

It’s About Life

In the end, Arnold says, her experience with Thomsen taught her something important—not about death, but about life.

“What we learned from him is that, first of all, we do need to be looking at death face to face. No one should tell anybody else how to do this, but I think there’s a lot to gain from looking at it—not just at the end, but in relation to the end. What is life about? What is today about? Tomorrow isn’t here yet, so what do I want my life to be about today? That, to me, is the goal of doing this work.”

In the end, as much as we may avoid the subject, we all have our own expiration dates—we just don’t know what they are yet. Arnold sometimes wonders how she would respond to a terminal diagnosis herself. Would her work still have meaning? Would she find joy in little things, as her friend Mo did at the end?

In the meantime, she continues to teach her classes and organize events and counsel seniors who come to her for advice. And she continues to let her involvement with death inform her thinking about life.

“Advanced directives are just documents,” she says. “The medical people need them. But what’s interesting to me is the thought that has to go into them. So that means people have to look at what their values are, what their beliefs are, what their goals in life are, what quality of life means to them, all of these things. If they’re really thinking about it and taking it seriously, they’ve got to look death in the face and figure out what their relationship is to it. And that means, ‘What’s your relationship to life?’”