AS HE RETIRES from the Board of Trustees this spring after a tenure of almost 30 years, including nine years as chair, Stewart Smith ’68 has found himself doing a few calculations. Between his father, the late H. Russell Smith ’36, and himself, he estimates that the Smiths have been active members of the College family—as students, engaged alumni and trustees—for roughly two-thirds of the College’s 130-year existence, including more than half a century with at least one Smith on the Board of Trustees and a grand total of 27 years as chair. And that family history remains open-ended since he’s also the father of two Pomona graduates—Graham ’00 and MacKenzie ’09.

AS HE RETIRES from the Board of Trustees this spring after a tenure of almost 30 years, including nine years as chair, Stewart Smith ’68 has found himself doing a few calculations. Between his father, the late H. Russell Smith ’36, and himself, he estimates that the Smiths have been active members of the College family—as students, engaged alumni and trustees—for roughly two-thirds of the College’s 130-year existence, including more than half a century with at least one Smith on the Board of Trustees and a grand total of 27 years as chair. And that family history remains open-ended since he’s also the father of two Pomona graduates—Graham ’00 and MacKenzie ’09.

“So it runs really deep in the family,” he notes with a wry smile. “We bleed Pomona blue—there’s no question—and for many, many, many, many decades.”

It’s a connection, however, that almost didn’t happen. “My dad had applied to Pomona, and was admitted, but realized that he could not afford $300 tuition, plus $400 room and board, so he set out to drive to the University of Redlands to accept its offer, which included financial aid,” Smith says. “On the way he stopped at Pomona. Trustee Clarence Stover happened to be in the Admissions Office at the time, and overheard Dad explaining that he needed to withdraw his application because he couldn’t afford Pomona. On the spot, Mr. Stover offered Dad a job as a carpenter’s assistant and, based on that generosity, Dad entered Pomona. A lot of things might have been different had this chance encounter not occurred. For example, it was in Claremont several years later that Dad met R. Stanton Avery ’32, and one consequence of that partnership is the Smith Campus Center.”

It’s perhaps ironic that Smith will be the first trustee to leave the board because of the mandatory term limits that he proposed and succeeded in passing some years ago—but he also believes it is fitting. When asked how he feels about leaving the board after so many years of service, he quotes Pomona’s seventh president, David Alexander: “The essence of Pomona College is constant renewal.”

It’s a perspective, he believes, that comes with the long view of Pomona’s history that he’s been privileged to gain over the years. “We come here. We do the best we can for the College. We try to provide it with additional resources and improve it in whatever ways we can. And then the wheel turns, and we move on. And others now, other very competent trustees are in place. And it’s a process that is far bigger than any one trustee, even with 30 years of service.”

While he was growing up, Smith was aware of his dad’s deep affection for his alma mater, but he says he never felt any pressure to attend Pomona himself. In 1964, however, after a visit to campus, he decided to apply for early admission. “I can’t remember any thought process I had at the time,” he says. “It just sort of happened.”

But he has much clearer memories of what happened after he arrived. “I’m an example of someone who was an insecure high school student when I came here, and I was able to find outlets,” he says. “I was class president and chair of the student court and some things that I wouldn’t have thought were in my wheelhouse coming into college. And I graduated with considerably more self-confidence and self-assurance, as well as a very good education.”

In particular, he remembers how Professor of Politics Hans Palmer, now emeritus, took him aside and pushed him to do his best. “He wasn’t letting me off the hook—a B-plus wasn’t good enough if I could do better—and that was one of the best things that could have happened to me,” he recalls. “I ended up realizing that I had an obligation to myself—if I’m going to spend the money to come to Pomona, I should maximize what I get out of it.”

It was after graduation, when he went on to Harvard Law School, that Smith would realize just how much he had gotten out of his Pomona education. “It boosted me on to a really great law school where I found the work to be less intensive than it was here at the College,” he explains. “So I certainly did well there, and it’s also served me throughout my life.”

In fact, looking back, he attributes his extensive volunteer service in a number of wide-ranging fields to the breadth of his Pomona education. Pomona, he says, left him conversant and interested in a variety of areas beyond his economics major or his law degree. “I’ve served as chair of an art museum, a college, a university library, chair of the Huntington Library,” he says. “I’m on the board of a dance company and a theatre company. I was president of a children’s museum and of the Little League. I’m missing a couple, but the point is that they’re varied. It’s a perfect example of the liberal arts making everything more interesting throughout your life.”

He doesn’t recall who asked him to join Pomona’s Board of Trustees in 1988, but he assumes it must have been President Alexander. What he does remember clearly is that he was “flabbergasted that they would ask me to do such a thing. I’d been involved in Torchbearers and so forth, but I didn’t think of myself as a trustee. But I instantly accepted. And I’ve certainly never regretted it.”

During the ensuing three decades, he’s seen lots of changes, not only at the College but on the board itself. “The board used to meet downtown,” he recalls. “We met 10 times a year—eight of them not on campus. Now we always meet here on campus. Somehow, just that change seems symbolic—that this is really all about the College and how we’re doing, rather than having trustees off in their own world.”

Asked what he’s proudest of from those years, he pauses to think. “The things that jump out at me are the truly transformational activities that the board was able to support,” he says finally. “Policies on diversity and sustainability, for example. Or on accessibility to the College and the financial resources to ensure that, like the no-loan policy. Or the decision that faculty salaries should be competitive with the best in the country. Or decisions around the endowment—our role was just supportive, but the growth of the endowment has been impressive. I think it was $230-something million when I joined the board, and today it’s over two billion and obviously has helped bring the College to the very forefront.”

Most recently, Smith helped add to that total as chair of the highly successful Daring Minds Campaign, which concluded at the end of 2015 with a total of more than $316 million raised.

During those 30 years, he’s worked with only three presidents—two of whom he helped to hire. “That was a particular privilege,” he says, to have the opportunity to participate in those two searches. And we came up with two really great presidents, I believe, so it was all quite worthwhile.”

On a more personal note, he remembers the pride and pleasure he took in presenting two of his children with their Pomona College diplomas, though he also recalls some nervous moments leading up to those events. “One of the roles of the board chair here, unlike many other institutions, is to personally sign every diploma,” he says with a laugh. “And in the early days, we used a fountain pen, or kind of a quill pen. And when you’re not used to using that kind of pen, it can be very difficult. You would get halfway through somebody’s name, and it would run out of ink. Or you had too much ink, and it would get really bloody. And you’ve got 300 of these to sign. So when I got to sign my son’s diploma, I was a nervous wreck. I’m sitting and I’m looking—‘Graham Russell Smith’—and I somehow have to sign with this pen with just the right amount of ink and without my hand quivering and so forth. So when my daughter came through, I resolved that I would just sign them and I wouldn’t look at the names so that when I signed hers, I wouldn’t be aware that I was about to sign my daughter’s diploma.”

The story also prompts a confession from an earlier phase in his life. “When I graduated from Pomona,” he says, “the board chair was—who? I’ve forgotten. But it wasn’t my dad. But several years later, he became board chair, and so—I’m ’fessing up here—I informed the College that I had lost my diploma. I hadn’t, actually, but I said I had and asked if I could have another one. They said, ‘Of course—we have a procedure for that.’ And so, I ended up with a diploma signed by my father, and it’s hanging on the wall of my office. If you were to open the frame of the picture, you would find behind it my actual, original diploma, but the one that you can see is the one signed by H. Russell Smith.”

PSYCHOLOGY: Assistant Professor Ajay Satpute

PSYCHOLOGY: Assistant Professor Ajay Satpute HISTORY AND CHICANA/0 LATINA/0 STUDIES: Associate Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval

HISTORY AND CHICANA/0 LATINA/0 STUDIES: Associate Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval I received my Pomona College Magazine yesterday, opened it this morning to the last page and came unglued to see Virginia Crosby’s beautiful smiling face.

I received my Pomona College Magazine yesterday, opened it this morning to the last page and came unglued to see Virginia Crosby’s beautiful smiling face. “The Cane Mystery” article in the PCM summer 2016 issue was interesting and reminded me of the cane which I now have. The cane belonged to my father, Robert Boynton Dozier (1902–2001), Class of ’23.

“The Cane Mystery” article in the PCM summer 2016 issue was interesting and reminded me of the cane which I now have. The cane belonged to my father, Robert Boynton Dozier (1902–2001), Class of ’23.

The play, written by Valdez, is based on the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial and the Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in early 1940s Los Angeles. The play tells the story of Henry Reyna and the 38th Street gang, who were tried and found guilty of murder, and their subsequent journey to freedom.

The play, written by Valdez, is based on the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial and the Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in early 1940s Los Angeles. The play tells the story of Henry Reyna and the 38th Street gang, who were tried and found guilty of murder, and their subsequent journey to freedom.

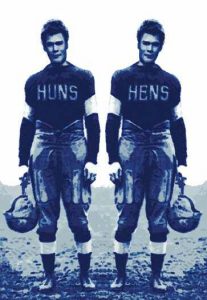

1. Huns to Hens

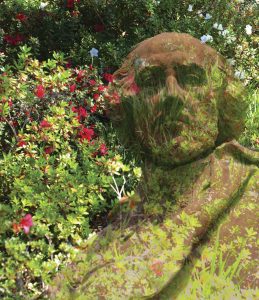

1. Huns to Hens 2. The Shakespeare Garden

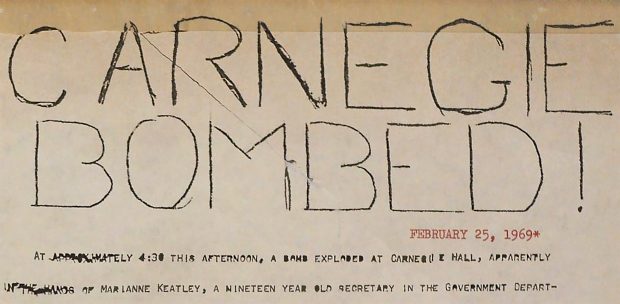

2. The Shakespeare Garden 3. Things That Go Bump

3. Things That Go Bump 4. The Flying Sailboat

4. The Flying Sailboat 5. The Duke and the Madonna

5. The Duke and the Madonna 6. The Borg and the Borg

6. The Borg and the Borg

8. The Roosevelt Shovel and Oak

8. The Roosevelt Shovel and Oak 9. All Numbers Equal 47

9. All Numbers Equal 47

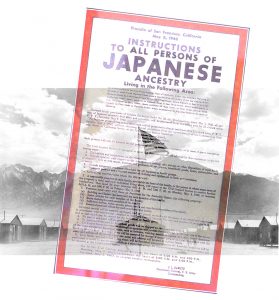

Desai: “… By now, we can accept as historical fact that the Japanese internment happened in the United States, and most people agree that it’s one of the darkest periods in American history. But the root causes of why the government so explicitly targeted Japanese Americans can be hard to parse out, so we talked to Pomona History Professor Samuel Yamashita. He said that the causes of the internment can be traced back to four distinct historical contexts, starting with the advance of European and American imperialism in the 19th century.”

Desai: “… By now, we can accept as historical fact that the Japanese internment happened in the United States, and most people agree that it’s one of the darkest periods in American history. But the root causes of why the government so explicitly targeted Japanese Americans can be hard to parse out, so we talked to Pomona History Professor Samuel Yamashita. He said that the causes of the internment can be traced back to four distinct historical contexts, starting with the advance of European and American imperialism in the 19th century.”