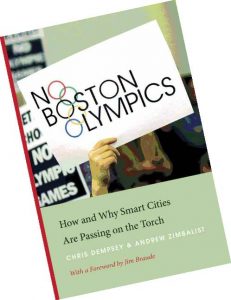

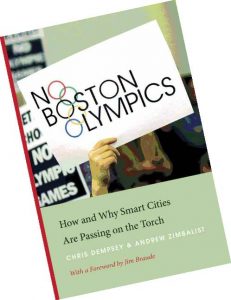

No Boston Olympics

How and Why Smart Cities

Are Passing on the Torch

By Chris Dempsey ’05

ForeEdge 2017 | 232 pages | $27.95

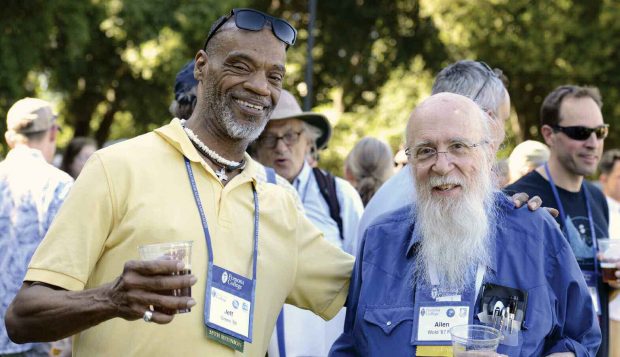

YOU COULD SAY David slew Goliath in Boston—in an Olympian-scale triumph. Christopher Dempsey ‘05 was one of the leaders of the No Boston Olympics campaign that successfully shut down the Boston 2024 Olympics bid. It is a story of how a scrappy grassroots movement beat a strapping, well-armed initiative. In the book he coauthored, No Boston Olympics: How and Why Smart Cities Are Passing on the Torch, Dempsey tells the tale and offers a blueprint that shows how ordinary people can topple extraordinary giants.

Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham interviewed Dempsey. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

PCM: Can you unpack the conventional argument that the Olympics are good for a city? What is hosting supposed to do for a city? What’s the myth, and if you can call it that, the romance behind it?

Dempsey: The International Olympic Committee has often had some success telling cities that hosting the Olympics is an opportunity for them to be seen on the world stage, and to enter an exclusive club of world-class cities that have hosted the Olympics, and to leave a legacy from the investments that are made by Olympic hosts to support the Olympic Games. The reality is that the International Olympic Committee is asking cities, in the case of the Summer Olympics, to spend somewhere between $10 billion and $20 billion in costs for a three-week event. And that event brings in revenues that are typically around $4 billion or $5 billion.

The host city and the taxpayers have to make up the difference. And, at the same time, economists have not found any evidence that the Olympics boosts your city’s economy in the long term, that it makes you a more attractive trading partner, or a place for a future business investment, or that you’re really benefiting your city in any sort of long-term way. So the actual reality of the Olympics is that they’re a very expensive and risky proposition with very little benefit. But, traditionally, the IOC has had some success getting Olympic boosters focused on some of those more ephemeral benefits to get them to ignore some of those costs.

PCM: When did it crystallize for you that you were going to co-helm this grassroots movement?

Dempsey: We came together in the fall of 2013, six months or so after there were initial reports in the media in Boston that a powerful group of people was coming together and forming to try to boost the games. What you saw in Boston, similar to the bidding groups in many cities, is that the people that formed that group were people who stood to benefit personally in some way from hosting the games. So the best example in Boston is that the chairman of the bidding group for Boston 2024 was also the CEO of the largest construction company in Massachusetts. Obviously, the Olympics would have been great for the construction industry in Boston because of all of the venues and stadiums that needed to be built for the games.

But there was a very powerful group of people that included the co-owner of the Boston Celtics, the owner of the New England Patriots, Mitt Romney (the former presidential candidate and former governor of Massachusetts). It eventually included the mayor of Boston himself. So it was a very powerful group of people, and a lot of the institutions in Greater Boston and Massachusetts that would typically ask some tough questions of the bid and be skeptical of a really expensive proposal like this pretty much stayed silent. And we saw that was going to be the case because it turned out that many of the people that were pushing the bid were also people that were on the boards of directors or donors to a lot of these institutions that would typically be the financial watchdogs.

So we saw that this was a real juggernaut, and we also saw that opposition was going to have to come from the grass roots because there was not going to be much institutional opposition. Seeing that, we said, “We think there’s a very good case to make that this is a bad idea for our city’s future. We don’t want to see this region become focused on a three-week event at the expense of some of our long-term goals as an economy and as a society. And so we should form a group to start to raise some of those questions and some of those arguments against the bid.”

PCM: When did the momentum start taking off for you in terms of gathering support?

Dempsey: The high-water mark for the boosters was in January of 2015, when they were victorious in a process that the United States Olympic Committee had run to determine which city would be the U.S. bid. Boston 2024 beat out Los Angeles; Washington, D.C.; and San Francisco.

There was a lot of excitement in Boston about the fact that the United States Olympic Committee chose our city. In fact, the polling in January of 2015 showed that support was around 55 percent, and opposition was only around 35 percent. So we had some pretty daunting odds at that point. I’ll always remember that day of the announcement, President Barack Obama tweeting his congratulations to Boston on winning the USOC bid. That was the kind of influence we were going up against.

Up to that point, the boosters behind Boston 2024 had shared very little information about what the bid entailed and about what the contract with the International Olympic Committee would require. Residents were just hearing the basic talking points that Boston 2024 put out, things like promises about no taxpayer money and glossy photos and images of what the bid would look like.

And that’s very typical for Olympic bids: boosters focus on these happy, positive moments. But over time the boosters were forced, by us and by others, to start sharing more information about the budget and the costs, and the contract with the IOC. And it was a death by a thousand cuts for the boosters—as more and more information came out, Bostonians liked the bid less and less.

As residents got more educated on the pros and cons, they determined that this was not a good idea for our city’s future. And so by February, the polling was pretty much split, where support and opposition were both around 45 percent. And then by March we had successfully flipped the numbers from those January numbers. From there on out, support for the bid hovered between 35 and 40 percent for the remaining life of the bid.

PCM: How were you mobilizing support?

Dempsey: Probably what we did best as an organization was work with the media to make sure that they were telling both sides of the story, arming them with facts and quotes and numbers about what was really going on with this bid.

It was very much a grassroots movement. We had an average contribution size of about $100, compared to Boston 2024, whose average contribution size was north of $40,000. They spent about $15 million on the bid. We spent less than $10,000. A lot of our organizing was social media, where we were able to build communities of supporters. But it was also old-school campaign tactics, such as holding organizing meetings and rallying people to attend a series of public meetings on the bid.

Sometimes it was as simple as making sure that we passed out signs to people at those public meetings so that they could express their opposition to the bid. The cover of the book became kind of the iconic image of Boston’s Olympic opposition—regular citizens expressing their concerns. Our brand became that of representing regular people, whereas Boston 2024 was seen as a group of very wealthy, successful and powerful people who lacked public support.

PCM: Did you find that there’s something unique about Boston citizens?

Dempsey: I don’t know if we’re unique, but I do think we have a proud history of being engaged in these types of civic debates. It is a part of the DNA of the city and the people who live here. The very first public meeting, that became the cover of our book, was held in a building that’s across the street from where some of the patriots of the American Revolution are buried. It’s part of who we are; we have that proud tradition of standing up for ourselves and not being afraid to take on some powerful forces.

So this is just one story in a long line of stories in Boston’s history where people have done that.

PCM: Was there a turning point in the campaign? There were 200 days from when the governor was inaugurated to when the bid was canceled, is that right?

Dempsey: Exactly 200 days. Which was fast, but it wasn’t sudden. Probably our most important talking point centered on the taxpayer guarantee. The International Olympic Committee requires the city that is bidding on the games to sign a contract that says that the city taxpayers are the ones who are responsible for any cost overruns.

And that fact contradicted the promises that the Boston 2024 boosters were making—that there were no taxpayer dollars needed for the games. So we kept hammering that point. It was a constant drumbeat and no single day or event. Just an educational process over many months.

PCM: You dedicate the book in part to Boston’s journalists. Why, and what was their role in this process?

Dempsey: They really are heroes in this story. This is particularly true of some young reporters who were ambitious and hardworking and willing to dig in on the details of the bid and make sure that the other side of the story was being told. Boston 2024 was spending tens of thousands of dollars a month on media and PR consultants to get their story out there. If journalists listened only to the powerful and connected, then our side never would have been able to get its message out. But because we were taken seriously, because journalists were doing independent research that uncovered some of the drawbacks and errors of the bid, the public could make an informed choice.

Here’s a specific example of the press’s impact. WBUR, which is one of the two NPR public radio stations in Boston, commissioned and published a monthly poll surveying residents about their opinions of the bid. That meant that we—and the USOC and IOC—could see support declining. We didn’t have to wait a year for a referendum or another opportunity for the public to be heard. It wasn’t cheap for WBUR to commission those polls, but it had a tangible impact on the debate—that’s great journalism.

We really feel fortunate that the media was so robust here. I think we would have had a very different outcome if it weren’t for those newsrooms.

PCM: Is there a way the Olympics can be made more egalitarian and more affordable?

Dempsey: If you think about the International Olympic Committee’s business model, it essentially started in 1896 with the first modern games in Athens. It probably made some sense in the 19th century to move the games around to different cities because that was the only way that people could experience the Olympics. It was based on the model of the World’s Fair, which was quite successful in the 19th century. But since 1896, humanity has invented the radio, television, the Internet, Pomona College Magazine, air travel. There are all these different ways to communicate and interact now that didn’t exist in 1896.

Today you beam the activities to billions of television sets. And people who want to see the Olympics in person could get on a plane and have not more than one or two airline connections to get to wherever it is, whether it would be Los Angeles or Athens or London or somewhere else. There’s a strong case to make for a permanent location or a small number of semi-permanent locations that would host the games.

Unfortunately, I’m very pessimistic about the International Olympic Committee’s willingness to change. The IOC is composed of roughly 90 people who are self-appointed. Many of their positions are hereditary, so it includes people like the princess of Lichtenstein and the prince of Monaco and the prince of Malaysia. These are fabulously wealthy people who are not used to hearing “no”—they’re used to getting their way. And as long as they still have one or two cities bidding every cycle, they’ll perpetuate this model no matter how inefficient and wasteful it is for the host cities.

I wish that I were more optimistic about the IOC changing, but as long as they stay undemocratic and unregulated, it’s hard to see them really having the right incentives to change.

PCM: Did you get a lot of push-back personally? Did anyone accuse you of poor sportsmanship for spearheading this campaign?

Dempsey: Early on, we were called cynics and naysayers—if not much worse. It was important for us to be clear that we loved Boston and that we thought Boston could host the Olympics, but that we shouldn’t because it put our city’s future at risk. And by reframing the question away from it being a kind of competition about who has the best city and instead turning it into a much more sober public-policy choice about whether this is a good proposal for us to embrace, we got people to move beyond the question of pride in your city and instead into the question of priorities. Did people want our elected leaders focused on the Olympics or on more-important challenges in transportation, education, health care, etc.?

Eventually we became seen as the scrappy underdogs—and thankfully, a lot of people root for underdogs.

PCM: What are a few things in your blueprint for citizens who want to challenge Olympic bids in their own cities? What is the advice you’d give to the powerless who are seeking to advocate for their greater, best interest?

Dempsey: First, when it comes to Olympic opposition, the facts are on your side. The boosters of an Olympics do not have a very good track record to run on, and they don’t have a lot of good data and information on their side. So you’re starting from a good place there, even though you’ll never have the power and resources that Olympic proponents will have. Second, the International Olympic Committee is truly out of touch with what regular people w want and need, and the more that you can expose the IOC as a selfish, short-sighted, opaque institution, the more you’ll help your cause, and you’ll expose that what’s best for the IOC is often the opposite of what’s best for host cities, and vice versa.

The cost and complexity of organizing citizens has come down. Underdogs and outsiders can really still make an impact on the debate—and that impact can be amplified on Twitter and Facebook. We often bemoan the negative impacts of those platforms, but they can also be powerful tools.

PCM: What is the broader significance of the story you tell for citizens who will never have an Olympics bid in their cities?

Dempsey: Olympic bids raise a lot of questions around how public resources are used to advance common goals. We should always be challenging and questioning public expenditures to make sure we’re getting the impacts and results we need as a society. Many cities decide to give public subsidies to stadiums, arenas or convention centers when those public dollars would be much better spent on education, transportation or health care.

PCM: Do you have any thoughts on the LA bid decision that’s coming down in September?

Dempsey: People in Southern California have very warm memories from the 1984 Olympics, and that is driving a lot of the support for LA’s bid for the 2024 Games. which replaced Boston’s bid in 2015. I think Angelenos and Southern Californians are forgetting that 1984 was a unique situation. For the 1984 games, there were only two cities that bid. The first was Los Angeles, and the second was Tehran, Iran. And Tehran actually had to drop out of the running on the eve of the Iranian Revolution. So that left Los Angeles as the only bidder in the IOC’s auction.

As anyone knows, when you show up to an auction and you’re the only bidder, you get a really good price. And so Los Angeles in 1984 was able to say to the IOC, “We’re not going to build new venues. We’re not going to sign the taxpayer guarantee. We’re going to negotiate the television contracts, and we’re going to get the profits from those.” Los Angeles today is not in the same position, because Paris is also bidding. In fact, Mayor Garcetti had said that he will be signing the contract that puts Los Angeles taxpayers on the hook. That’s a fundamental difference from 1984.

That’s something that Garcetti doesn’t want to talk about and the boosters behind LA 2024 don’t want to talk about, but it is a reality of what they have agreed to with the IOC.

I give LA 2024 credit because they are creating a plan that uses a lot of existing and temporary facilities, but they are still fundamentally proposing a risky deal. Imagine a corporation that wanted to locate in Southern California and said, “We want to move here and we promise to add some jobs, but if we’re not profitable as a company, we want LA taxpayers to make up the difference.”

That would be an outrageous demand for a private business to make. But that’s essentially what LA 2024 is doing, and the mayor is going along with it. I think the LA region deserves more of a discussion around what the pros and cons are here and whether this is truly a good deal for the city or whether they’re sort of coasting off of the warm feelings and warm memories that people have from 1984.

PCM: So some city somewhere needs to host the Olympics, right? Is there a place you think would be a great fit?

Dempsey: For me it’s more about the model. If you were going to choose a permanent location, I think you could make a case that Los Angeles would be a good one. LA is good at putting on TV shows, which is what the Olympics is more than anything else. Obviously Athens, because of the history with Greece, would be another interesting location to consider. Or maybe London. I don’t know what the answer is there, but I think the most important thing is that we try to make cities aware that, around the world, there are a lot of drawbacks.

Since Boston dropped out, Hamburg, Germany; Rome, Italy; and Budapest, Hungary, have all dropped their bids for the 2024 Olympics. And they’ve all pointed to Boston and said, “Boston made a smart decision here, and we’re going to make the same decision to drop out. We have other things that we want to spend our time and limited taxpayer dollars on.”

So you are seeing fewer cities bid. LA and Paris are going ahead for 2024, and we’ll see kind of what the bidding landscape looks like in years ahead.

PCM: So the romance is fading, right?

Dempsey: I think that’s true. The IOC has been greedy in a sense. They’ve extracted all of these concessions out of prior hosts, and potential host cities are realizing that the contract that they are being asked to sign is just not a reasonable one for most democracies. You’re seeing a narrowing to a couple of cities that have hosted before and feel like they have the venues in place, and then you’re seeing dictatorships—places like Russia and China that don’t care about popular opinion and are doing it for the spectacle or to glorify their autocratic leaders.

PCM: Do you have a favorite Olympics event?

Dempsey: I was about 10 years old when the Dream Team played in Barcelona, so I’d go with that. It’s also fun to watch the quirky and obscure events that you see only every four years. At No Boston Olympics, we always said the three weeks of the Olympics would be fun. But you have to look at the long-term costs, not just the party.

In high school, follow your mother’s example and get involved in community service, volunteering at a food bank and local homeless shelter. Fall in love with the work partially because you find it fulfilling and have a deep interest in understanding the problems of the people you’re helping.

In high school, follow your mother’s example and get involved in community service, volunteering at a food bank and local homeless shelter. Fall in love with the work partially because you find it fulfilling and have a deep interest in understanding the problems of the people you’re helping. Know that you don’t want to follow in your brother Nick’s footsteps at Pomona College, but end up deciding it’s the best place for you anyway. And though you’ve always thought philosophy was abstract and boring, take a first-year seminar with Professor Julie Tannenbaum in medical ethics and discover that the field deals with intriguing real-world challenges.

Know that you don’t want to follow in your brother Nick’s footsteps at Pomona College, but end up deciding it’s the best place for you anyway. And though you’ve always thought philosophy was abstract and boring, take a first-year seminar with Professor Julie Tannenbaum in medical ethics and discover that the field deals with intriguing real-world challenges. Love your class in forensic psychology with Claremont McKenna College Professor Daniel Krauss so much that you end up as his research assistant. Major in both philosophy and cognitive science because you see them as two ways of understanding human behavior; then spend a summer with Harvard’s Mind/ Brain/Behavior program in Trento, Italy.

Love your class in forensic psychology with Claremont McKenna College Professor Daniel Krauss so much that you end up as his research assistant. Major in both philosophy and cognitive science because you see them as two ways of understanding human behavior; then spend a summer with Harvard’s Mind/ Brain/Behavior program in Trento, Italy. Inspired by a lecture by author/activist Bryan Stevenson on mass incarceration, follow his advice about getting “proximate” to the problem. Spend a summer working behind barbed wire at Patton State Hospital, a psychiatric facility in the California correctional system. While there, take an interest in psychopathy, which you come to believe is misunderstood.

Inspired by a lecture by author/activist Bryan Stevenson on mass incarceration, follow his advice about getting “proximate” to the problem. Spend a summer working behind barbed wire at Patton State Hospital, a psychiatric facility in the California correctional system. While there, take an interest in psychopathy, which you come to believe is misunderstood. As a senior, write two theses on the subject of psychopathy—an examination of the ethical theory of the blameworthiness of psychopaths for your philosophy major, and a study of inhibition deficits in high-functioning psychopaths for your “cog-sci” major.

As a senior, write two theses on the subject of psychopathy—an examination of the ethical theory of the blameworthiness of psychopaths for your philosophy major, and a study of inhibition deficits in high-functioning psychopaths for your “cog-sci” major. Conclude that psychopathic traits should be treated as a mitigating factor in both moral and legal domains, and decide you want to study the subject further to be able to influence public policy. Gain admission to a top Ph.D. psychology program at UC Davis with a professor whose research offers opportunities to pursue your chosen work into the future.

Conclude that psychopathic traits should be treated as a mitigating factor in both moral and legal domains, and decide you want to study the subject further to be able to influence public policy. Gain admission to a top Ph.D. psychology program at UC Davis with a professor whose research offers opportunities to pursue your chosen work into the future.

Thank You, Jordan!

Thank You, Jordan! Introducing Regional Book Club Discussions

Introducing Regional Book Club Discussions

The Handmaid’s Tale

The Handmaid’s Tale