Japan may be the economic canary in the coal mine, Matt Sanders ’00 believes. And at the same time, it may already be transforming itself into the economy of tomorrow.

Japan may be the economic canary in the coal mine, Matt Sanders ’00 believes. And at the same time, it may already be transforming itself into the economy of tomorrow.

Once a powerhouse, Japan’s economy has struggled for the past 30 years. Much of that sluggish growth, says Sanders—the founder and president of East Gate Advisors, a U.S.-Japan business advisory firm—can be attributed to demographics. “Japan leads the world in its aged population, and there’s also the fact that the Japanese population has actually been in decline for seven years,” he says. Add to that the tendency for Japanese women to quit the workplace after they marry, and you have a declining number of workers supporting an increasingly expensive non-working population.

What’s Next For:

Revolutions?

Syria?

Mexico?

Japan?

The United States?

Earthquake Safety?

Climate Action?

California Water?

Climate Science?

Solar Energy?

California Fruit Farming?

Technology Investing?

Nanoscience?

Digital Storage?

Artificial Intelligence?

Cyber-Threats?

Social Media?

Space Exploration?

Science Museums?

The Sagehen?

Biodiversity?

The Blind?

Big Data?

Mental Illness?

Health Care Apps?

Maternity Care?

Etiquette?

Ballroom Dance?

Thrill Seekers?

Outdoor Recreation?

Funerals?

Writers?

Movies?

Manga?

Alt Rock?

Women in Mathematics?

But with populations aging throughout the developed world and automation displacing more and more human workers, Sanders thinks other societies—including ours—may soon be in the same predicament. If so, he says, the liabilities that have hindered Japan’s progress may also be transforming it into the economy of the future.

That’s because the Japanese are integrating technology in general—and robotics in particular—into their society at a rate that Americans find mystifying. Americans remain leery about interacting with robots, but the Japanese have welcomed them enthusiastically.

Sanders points to the proliferation in Japan of such robots as Aibo, the cute little robotic dog; Asimo and Pepper, anthropomorphic robots designed to act like humans; and Paro, a cuddly robotic baby seal designed to work as a kind of therapy animal with dementia patients. These may seem like curiosities now, but in a world where fewer people are working and more people need care, such technologies may soon be necessities. “In the U.S., the lack of consumer and general public acceptance has a real tendency to hold that technology back in integrating into society, and that’s where you can see the Japanese sort of charging ahead,” Sanders says.

The resulting transformation of Japanese society, he says, will be just one more in a long line of periodic transformations. “Japan stays exactly the same for a long, long time, until some sort of event happens. And then it changes really quickly, like right before your eyes, overnight and radically. The place will stay exactly the same for 50 years, 100 years, 200 years. Then suddenly, something happens, and boom—it’s unrecognizable the next day.”

With the July 1 election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (widely known by his initials, AMLO) as president, Mexico stands at a historic turning point, one that leaves Professor of Latin American Studies Miguel Tinker Salas cautiously optimistic about the prospect for real change.

With the July 1 election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (widely known by his initials, AMLO) as president, Mexico stands at a historic turning point, one that leaves Professor of Latin American Studies Miguel Tinker Salas cautiously optimistic about the prospect for real change. Predicting the future in a conflict as multi-faceted as the Syrian Civil War is daunting, and Politics Professor Mietek Boduszynski says his thoughts on the matter have shifted several times, including last May, when the United States pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal.

Predicting the future in a conflict as multi-faceted as the Syrian Civil War is daunting, and Politics Professor Mietek Boduszynski says his thoughts on the matter have shifted several times, including last May, when the United States pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal. Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold.

Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold.

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era.

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era. As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant.

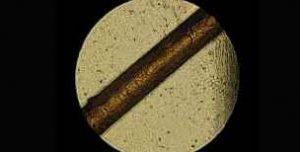

As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant. In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.

In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.

My favorite anecdote about growing up in the rural South is a childhood memory of sitting with my aunt and uncle at their red Formica kitchen table, which was strategically positioned in front of a double window looking out on the dirt road in front of their house. Each time a car or—more likely—a pickup would go by, leaving its plume of dust hanging in the air, both of them would stop whatever they were doing and crane their necks. Then one of them would offer an offhand comment like: “Looks like Ed and Georgia finally traded in that old Ford of theirs. It’s about time.” Or: “There’s that Johnson fellow who’s logging the Benton place. Wonder if he’s any kin to Dave Johnson.”

My favorite anecdote about growing up in the rural South is a childhood memory of sitting with my aunt and uncle at their red Formica kitchen table, which was strategically positioned in front of a double window looking out on the dirt road in front of their house. Each time a car or—more likely—a pickup would go by, leaving its plume of dust hanging in the air, both of them would stop whatever they were doing and crane their necks. Then one of them would offer an offhand comment like: “Looks like Ed and Georgia finally traded in that old Ford of theirs. It’s about time.” Or: “There’s that Johnson fellow who’s logging the Benton place. Wonder if he’s any kin to Dave Johnson.”