Susan McWilliams doesn’t mince words when it comes to predicting the future of the American Experiment.

Susan McWilliams doesn’t mince words when it comes to predicting the future of the American Experiment.

What’s Next For:

Revolutions?

Syria?

Mexico?

Japan?

The United States?

Earthquake Safety?

Climate Action?

California Water?

Climate Science?

Solar Energy?

California Fruit Farming?

Technology Investing?

Nanoscience?

Digital Storage?

Artificial Intelligence?

Cyber-Threats?

Social Media?

Space Exploration?

Science Museums?

The Sagehen?

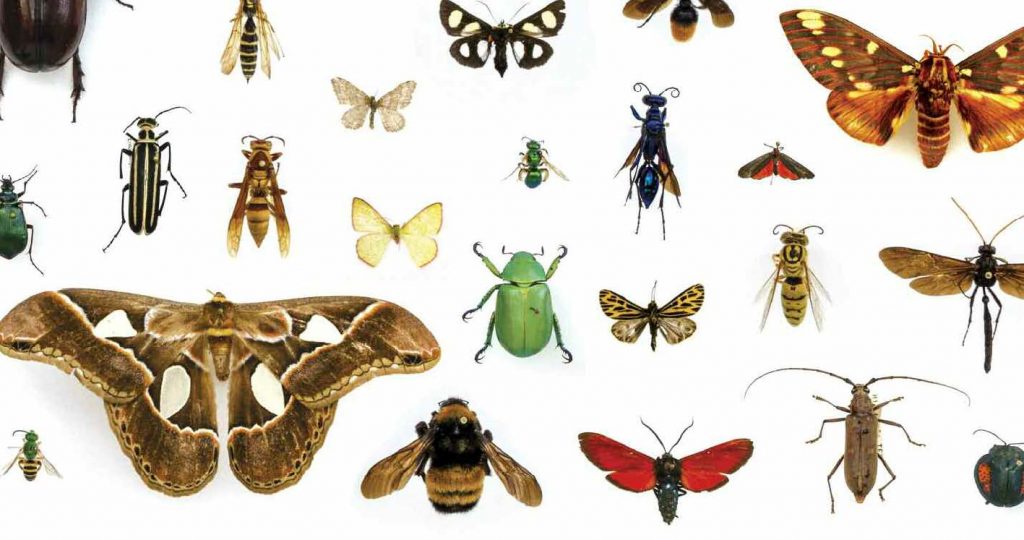

Biodiversity?

The Blind?

Big Data?

Mental Illness?

Health Care Apps?

Maternity Care?

Etiquette?

Ballroom Dance?

Thrill Seekers?

Outdoor Recreation?

Funerals?

Writers?

Movies?

Manga?

Alt Rock?

Women in Mathematics?

“Republics don’t last,” says Professor of Politics McWilliams. “I don’t think we should shy away from the assumption that this republic, like all other republics has an expiration date. If we acknowledge that, then we realize that it is our job to think about how to prolong republican government as much as possible. We should be asking ourselves: What are the specific dangers to republican collapse that we’re seeing now, and how can we mitigate those?”

Those dangers, says Professor of Politics David Menefee-Libey, include the current attacks on liberal democracy and the rule of law by the president and some of the most powerful people in government. “We should also be worried about the cynical ways so many people in the business and nonprofit worlds have responded—taking advantage of the system even as they work to erode it,” says Menefee-Libey. “They spend enormous amounts of money and work so hard to gain influence at the same time they talk trash about politics and governments in public. They seem to want the U.S. system to become more of an oligarchy, run by and for the rich and powerful, than a democratic republic.”

That sounds familiar to McWilliams, who studies the history of political thought. About 2,400 years ago, she says, Plato wrote about oligarchs and their contempt for democracy and linked the uncertainty in people’s lives to democracies that devolve into tyrannies. “Think about America now,” says McWilliams. “We have a low unemployment rate, but most Americans have lives that are very uncertain, where they’re living paycheck to paycheck, where they’re not sure what their children’s lives are going to look like. Plato says if you’re feeling that kind of overwhelming uncertainty, you’re going to be inclined to follow people who tell you, ‘I am certain about this.’”

An antidote to oligarchy and tyranny, suggests McWilliams, is liberal arts education. “The liberal arts are meant to educate in the arts of liberty; that’s where the phrase ‘liberal arts’ comes from,” says McWilliams. “(W.E.B.) Du Bois would say what we’re doing in American today is moving away from a mode of education that aims at civic and political empowerment, and we at places like Pomona need to do all we can to support liberal education everywhere.”

When you educate people, adds Menefee-Libey, it challenges parochialism and the ability to think that other people are somehow less human and less worthy of respect and inclusion in public life.

“I think the next 10, 20 years are going to be extraordinarily difficult, but I also think that there are ideas and leaders, policies and strategies that can get us out of this,” says Menefee-Libey. “I am not an optimistic person, but I am a hopeful person, and I think there’s a tremendous amount of hope.”

Japan may be the economic canary in the coal mine, Matt Sanders ’00 believes. And at the same time, it may already be transforming itself into the economy of tomorrow.

Japan may be the economic canary in the coal mine, Matt Sanders ’00 believes. And at the same time, it may already be transforming itself into the economy of tomorrow. With the July 1 election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (widely known by his initials, AMLO) as president, Mexico stands at a historic turning point, one that leaves Professor of Latin American Studies Miguel Tinker Salas cautiously optimistic about the prospect for real change.

With the July 1 election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (widely known by his initials, AMLO) as president, Mexico stands at a historic turning point, one that leaves Professor of Latin American Studies Miguel Tinker Salas cautiously optimistic about the prospect for real change. Predicting the future in a conflict as multi-faceted as the Syrian Civil War is daunting, and Politics Professor Mietek Boduszynski says his thoughts on the matter have shifted several times, including last May, when the United States pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal.

Predicting the future in a conflict as multi-faceted as the Syrian Civil War is daunting, and Politics Professor Mietek Boduszynski says his thoughts on the matter have shifted several times, including last May, when the United States pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal. Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold.

Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold.

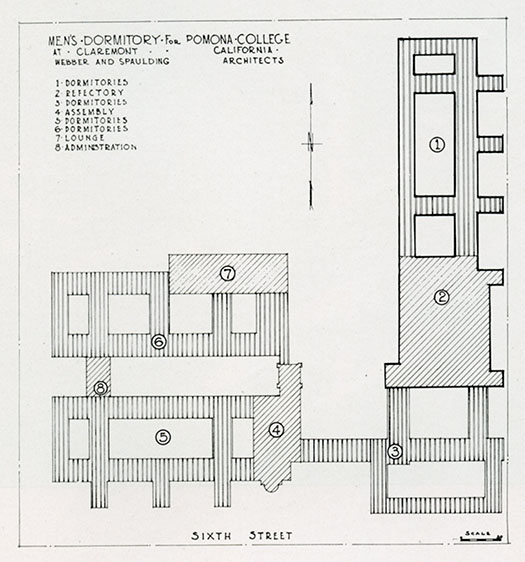

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era.

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era. As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant.

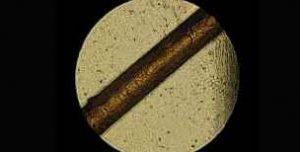

As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant. In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.

In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.