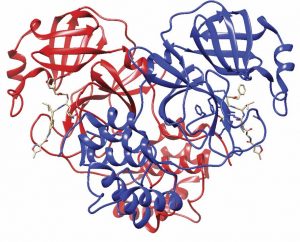

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX.

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX.

In an article published in the Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, Pomona College Professor of Chemistry Roberto Garza-López, DePaul University Professor of Chemical Physics John Kozak and Caltech Professor of Chemistry Harry B. Gray have shared their findings in order to contribute to the worldwide effort to end the pandemic. Titled “Structural stability of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease: Can metal ions affect function?” the article was picked by the journal’s editor to be part of a special issue to celebrate the publication’s 50th anniversary.

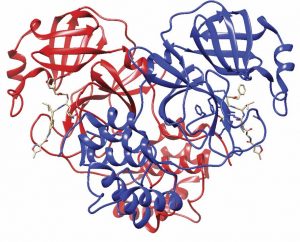

Using computational techniques employed in Garza-López’s lab and experimental results obtained in Gray’s lab, the team began working in February on the properties of these two pieces of the novel coronavirus. The virus uses its spike protein, 6VXX, to attach itself to human cells. Then, like a pair of molecular scissors, the protease, 6LU7, activates the virus by cutting its large polyproteins into smaller segments that can attack human cells. Both proteins are key to the virus’s ability to replicate.

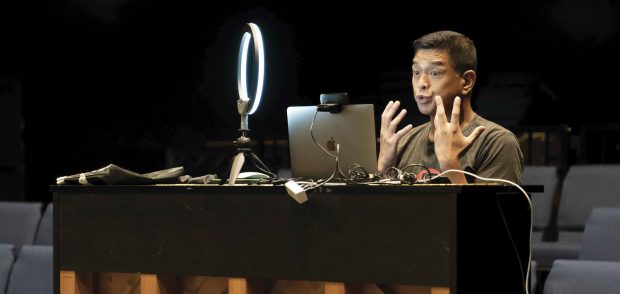

Through almost daily research via Zoom discussions, computational modeling and experiments, the researchers have discovered that several metals—including certain ions of zinc, copper and cobalt—could inhibit the normal functioning of those two vital pieces of the virus’s protein. Inhibiting either the attachment of the virus or the catalytic action that activates it could prevent the virus from wreaking havoc on individual cells and, ultimately, the immune system.

“The purpose of knowing the mechanism to inhibit the SARS-CoVid-2 virus is to guide the design of COVID-19-specific therapeutics and vaccines suitable for mass immunization,” says Garza-López. “Drug design will focus on the ability to stop the novel coronavirus before it attaches to human cells or reproduces itself. That’s why we believe the contribution of our last two papers and this one that was just accepted will be able to say something about this mechanism.”

The research team had already been studying the family of coronaviruses for a while before the global pandemic caused by the new coronavirus began. Then, in early February, a team of Chinese scientists shared the crystal structure of protein 6LU7 in the Protein Data Bank, an open-access digital data resource available to scientists around the world, with the aim of promoting scientific discovery. One day after 6LU7 was deposited by the Chinese team, Garza-López pulled the data to begin his work.

“I visualize the protein, and we go piece by piece and identify different pockets in which we can stop either the attachment of the virus or the catalyzation that is responsible for the polyprotein that will inject the machinery into the cell to replicate and destroy the immune system,” he explains. “Many simulations are performed daily to get the right inhibiting mechanism.”

As COVID-19 swept the world and turned into a global pandemic, Garza-López and Gray took to Zoom to conduct daily research meetings. Garza-López also oversaw 13 student researchers during the summer, including both students at Pomona College and high school students in Pomona’s summer enrichment program, known as PAYS. “Computational research has not slowed down, in spite of spending considerable time at improving my teaching online and having five PAYS students and eight Pomona College undergraduates this summer,” he says, adding that the students have had all the means necessary to continue their work uninterrupted without having to meet in person or put each other at risk.

“The new coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 illness is very unique. It’s very easy to transmit, which makes it more dangerous than the other coronaviruses, especially when it mutates and improves its efficiency,” says Garza-López. “We are interested in how its protein structure behaves and its points of weakness as well as the recent D614G mutation that has increased its efficiency of transmission 10 times.”

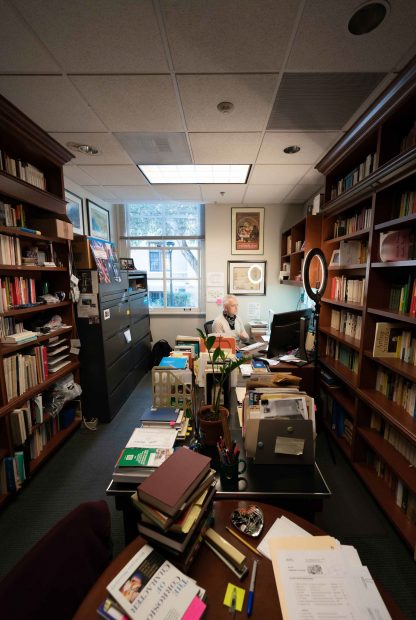

Garza-López, Gray and Kozak have a long history of studying proteins, how they interact, how they fold and unfold, how they react with certain metallic elements. Prior to their interest in coronaviruses, the team was working on the folding and unfolding of the proteins azurin and cytochrome C’ and energy transfer in special molecules called dendrimers. The improper unfolding of proteins has been linked to cancers and other diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Winning a Watson Fellowship is both a creative passport and a generous provision to wander the world and do independent research for a full year after graduation. However, just as it did to best-laid plans around the world, COVID-19 interrupted those of this year’s Watson winners.

Winning a Watson Fellowship is both a creative passport and a generous provision to wander the world and do independent research for a full year after graduation. However, just as it did to best-laid plans around the world, COVID-19 interrupted those of this year’s Watson winners. Plenty of folks consider campus radio station KSPC 88.7 FM an essential part of their daily routines.

Plenty of folks consider campus radio station KSPC 88.7 FM an essential part of their daily routines.

The Arrest

The Arrest Separate but Faithful:

Separate but Faithful: The Phantom Pattern Problem:

The Phantom Pattern Problem: Ripples of Air:

Ripples of Air: Hunting Nature:

Hunting Nature: Signature

Signature Reading Minds:

Reading Minds: Modern Family:

Modern Family: The Power of the Impossible:

The Power of the Impossible:

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX.

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX.