From left, Maryann Zhao ’18, Grant Steele ’18, Sal Daddario ’18, Aseal Birir ’18, Julia Foote ’18, Samantha Little ’20 and Michael Poeschla ’18. Photography by Joel Benjamin

They took different routes to the study of medicine, but the paths of a cluster of Sagehens—including at least a half-dozen from the Pomona College Class of 2018—have converged at Harvard Medical School. With a history dating to 1782 and 10 Nobel Prizes awarded for research conducted there, Harvard is one of the most prestigious and selective medical schools in the world, with only 3.2% of applicants accepted into its M.D. program in 2023. Maybe that’s why Maryann Zhao ’18 was literally speechless when she got the call that she was one of only 30 students in 2020 accepted into the school’s Health Sciences and Technology program, a research-focused medical track.

As New England’s leaves began their annual display of color last fall, a gathering of Sagehens who are soon to be doctors munched on pizza and drank soda in an empty classroom on the Harvard medical campus in Boston and talked about their experiences so far. They seemed relaxed and jovial despite the academic rigor of their programs.

Though they did not all start med school at the same time—gap years were common—most are near the end of the beginning, about to graduate medical school and advance into residency. Grant Steele ’18 already is a first-year urologic surgery resident at Massachusetts General Hospital and Michael Poeschla ’18 is far along in an M.D./Ph.D. program, with his research focused on understanding how human genetic variation impacts blood cell production and blood cancers, as well as aging. And he’s not the only Sagehen at Harvard studying to become a physician-scientist: Jessica Phan ’19 is also in the program.

Aseal Birir ’18 plans a different future. During medical school he discovered a compelling interest in drug development and became fascinated with the business side of medicine. This spring, he will complete Harvard’s five-year joint M.D./MBA program and is applying for positions in biotech investing.

Getting into medical school required taking courses like Intro to Cell Biology and Organic Chemistry. But for Birir, a chemistry major, an Africana studies class he took his freshman year changed his entire perspective on himself and the patients who might one day benefit from his work. During his second year at Harvard, Birir wrote an essay published in The Student Life, The Claremont Colleges’ student newspaper, encouraging fellow STEM majors to follow his lead. “No matter how you plan to use an undergrad degree in STEM, the lessons of Africana studies will impact you positively,” he wrote. “I encourage students in STEM fields to leave the safety of textbooks and problem sets for uncomfortable but meaningful lessons and discussions in Africana studies classes.”

That is but one example of how a liberal arts education has shaped these Sagehens who are aiming for the highest ranks of their profession. For some, it was memorable classes such as Genetic Analysis or a Spanish literature course on the Latin American Boom literary movement of the 1960s and 1970s. For others, it was varsity tennis, soccer or lacrosse, where they found a tight-knit family of fellow athletes without having to compromise academic pursuits. And again and again, these med students say, close and meaningful connections with faculty helped pave their way.

At Harvard, the Pomona alumni still cross paths. Steele, the first to graduate from medical school, is now finding fellow Sagehens—including some from other medical schools—among the residents he encounters in the operating room at Massachusetts General Hospital. “It really is special to look across the drapes in the OR and see a fellow Sagehen smiling back at you,” he says.

Here are the stories of some of the Harvard Med students from Pomona.

Sal Daddario ’18

Undergraduate Major: Neuroscience

Minor: Biology

Fast Facts:

- Programs like the Pomona Scholars of Science fostered his love for teaching and mentoring.

- Discovered his passion for medicine while working as a scribe at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center.

- Applying for a residency in anesthesia and wants to be a pediatric anesthesiologist.

- Finds balance in life through improv comedy and cherishes connections with fellow Pomona graduates at Harvard.

My very first exposure to the field of medicine was as a patient. When I was 11, I had an infectious disease that required multiple surgeries. I was in and out of the hospital for two months. I remember interacting with my doctors and being in awe of the way they worked: They collected information, made decisions, tried new things—and then I got better. In my 11-year-old brain, that was the coolest thing ever.

As I moved into high school and then college, I had a vague idea that I could become a doctor. Being a first-generation college student from a small, rural town in Ohio, I didn’t know many other career paths. When I arrived at Pomona, I was embraced in a way that shaped the path of the rest of my life. I still remember the support I received from professors in the sciences early on—especially from Professors Dan O’Leary and Nicole Weekes. They became my academic parents: I was always in their offices talking about the course, the fields, or our lives. They gave me books, they taught me how to read primary literature in the sciences, and they helped me see the different paths into my future. I had never had such impactful academic relationships in my life.

I was also embraced by the Pomona Scholars of Science program (big shout-out to Travis Brown). It was my very first introduction to mentorship. After benefiting from the support of the first-generation college student community at Pomona for my first year, I was able to jump into an educating and mentoring role myself in my second year. It was the first of many, many times in my life since where I had the opportunity to work to make my communities stronger. I found that I had a deep passion for education, supporting students and building positive learning communities.

While I was at Pomona, I gained clinical experience working as a scribe in the emergency department at nearby Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center. I found that as a physician, I would get to do tons of impactful, targeted patient education while also being part of a larger academic structure where I could work closely with residents and medical students. In medicine, I could be an educator and mentor for the rest of my life!

It was a bit hard to transition from Pomona to Harvard—it’s a huge institution with lots of hierarchy and slow change. Still, it’s been amazing to be in the heart of medicine, surrounded by incredibly bright clinicians, fantastic educators and powerful researchers. I’ve found that people here are very excited about changing the face of medical education, and I have gotten to work on projects for publication in medical education journals. I’ve used the skills I learned at Pomona in every research endeavor I’ve been involved in here at Harvard. I came into college without any of those skills, and I left Pomona ready to immediately engage in clinical research as a valuable member of the team. Now I’m applying to anesthesia residency programs with the goal of being a pediatric anesthesiologist.

Life as a medical student, in general, is very ebb-and-flow. Some weeks and months are among the hardest of my life—taking care of patients all day, going home and studying for exams at night, and working on research projects on the weekends. But other months, I’m able to strike a better balance. For me, that balance is improv comedy.

While I was taking two gap years in Chicago before med school, I started to do improv at the iO Theater. Initially something I did to make more friends in the city and have a bit of fun, improv morphed into a very large, meaningful part of my life. In my third year of medical school, I joined a cast at Union Comedy in Somerville, a Boston suburb, and started to do improv again around three times a week. It has become my sanctuary here, a place where for a few hours I don’t have to think about school, medicine, exams or residency applications. I can laugh with my friends and put on shows. I want to keep one foot in improv for the rest of my life. It has brought me so much joy.

Having other Sagehens at Harvard Medical School has been fantastic. The fact that I could come into this totally new world and be with the people I knew and loved to spend time with was very reassuring. I feel truly at home. We have shared almost 10 years of our educational journeys together. Our shared histories are such an important part of my sense of belonging here.

If I were giving advice to current Pomona students, it would be this: Figure out the thing that you love to do. Then do it. A lot. For me, that is teaching and mentoring. It was the most amazing part of my time at Pomona. My application to medical school was filled with the teaching I got to do at Pomona. Now my residency applications are again filled with the teaching opportunities I’ve had here at Harvard.

Medical schools like applicants who have something they really love to do, something that they light up when they talk about. I tell everyone still in college to figure out what is the thing that they like to do for hours and hours. And then figure out ways to do it more.

Aseal Birir ’18

Undergraduate Major: Chemistry

Fast Facts:

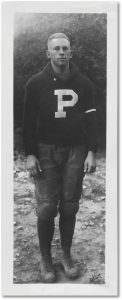

- Extracurricular activities like varsity football helped develop teamwork and leadership skills.

- Credits a liberal arts education for fostering broad thinking and research skills.

- Shifted focus from patient care to drug development due to unmet needs in certain diseases and personal interest in innovation.

- Combined medical and business education with an M.D./MBA program.

I was always passionate about science and was attracted to a career in medicine as a way to apply my passion for science to heal others. However, my definition of healing has taken on additional meaning during my 4 ½ years at Harvard Medical School.

During my time at Pomona, I was involved in a research project developing a breath test for pneumonia infections and working with a startup biotech company at the Keck Graduate Institute. Attempting to build and commercialize innovations in medicine showed me that this was an exciting way to impact health care and motivated me to pursue an MBA at Harvard Business School during my medical training. I’ll graduate with both an M.D. and an MBA this May.

Once I started medical school, my interests began to shift. I enjoyed treating patients with cutting-edge medicines, but I was exposed to numerous diseases with no treatments and high unmet need. This made me really interested in how drugs are discovered and developed. At Harvard Business School, I got exposure to the broader health-care landscape. I realized that working in drug development would allow me to have a scaled-up impact on patient care and that it was at the intersection of my interests in medicine, science and business. Thus I have decided not to apply to residency programs and to pursue a career in biotech after graduation.

My liberal arts education at Pomona gave me the foundation to think broadly in medical school about my interests, and that led me to expand my medical education to include business school. Additionally, a liberal arts education taught me how to learn, and that has enabled me to succeed in two very different academic environments: medicine and business.

I played on the varsity football team at Pomona all four years. Pomona-Pitzer football was critical to my development. My teammates, and now lifelong friends, taught me hard work, commitment and teamwork. I also learned how to work with a variety of personalities, how to lead and motivate others, how to fail (we lost quite a few games in my first two years but turned it around the last two seasons) and how to sacrifice for others around you.

If I were giving advice to incoming Pomona students, I’d tell them to take advantage of faculty office hours. You can build great relationships with professors and really grow as a student. I’d say, “Be a chemistry major!” (because it’s the best department at Pomona, in my unbiased opinion). I’d like to give a special shout-out to Professor Chuck Taylor.

Take more humanities classes than you think you should. Despite being a pre-med chemistry major, I found the Africana studies courses I took at Pomona to be the most influential.

Finally, use your first few years at Pomona to explore and remain curious about all career paths before you choose the one that’s right for you. And have fun—it’s college!

Maryann Zhao ’18

Maryann Zhao ’18

Undergraduate Major: Molecular Biology

Fast Facts:

- Pomona mentors fostered her love for research and independent learning.

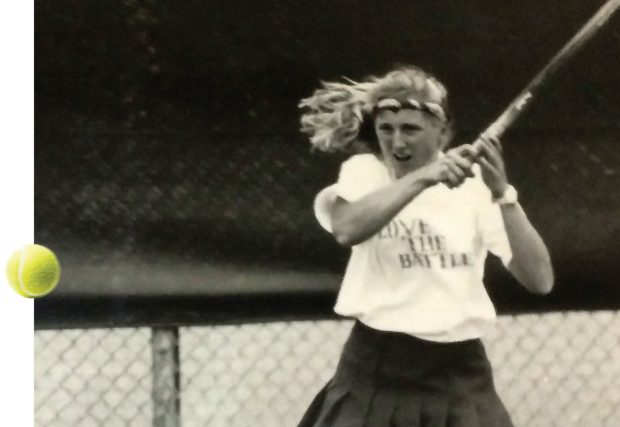

- Values the support and community found in extracurricular activities like the tennis team.

- Plans to focus on the ear, nose and throat field and is doing research on head and neck cancer at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

When I started medical school, I was considering some type of surgery as my specialty. But it wasn’t until surgery rotation in my clinical year that I discovered the field of ear, nose and throat (ENT) and fell in love with it. It’s an ideal mix of intricate anatomy, a diverse range of procedures and surgeries you can do and a patient population that is very meaningful to work with. Above all, I loved the people I worked with. I thoroughly enjoyed my time on the ENT service, working with the residents and attendings on the team, and I didn’t mind the long days. That was a big deciding factor for me.

I’m currently doing a research year at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, working in the lab of Dr. Ravindra Uppaluri, who is director of head and neck surgical oncology at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Dana-Farber. Our lab is focused on head and neck cancer models and is studying the immunology of the disease. One of the challenges of this field is the difficulty of creating models in the lab of head and neck tumors that closely resemble what is found in patients. I am currently tackling this problem by creating 3D models to study immune interactions in these cancers. I’m lucky to have such an excellent mentor who has forged a path as a surgeon-scientist.

Since the beginning of college, I’ve always really loved science and doing scientific research. My mentors at Pomona, specifically Professors Jane Liu and Daniel O’Leary, played a huge role in fostering my passion for research and providing a nurturing yet challenging environment for me to learn how to master the scientific process. What gets me most excited is how research can potentially impact someone’s life and improve care they receive. That’s what motivated me to go into medicine.

Research can be incredibly challenging. What’s really rewarding, though, especially for people who do end up being physician-scientists, is that while you are spending time with patients in the clinic, you may see how research you’re involved in is improving their outcomes—patients living longer and having a better quality of life. Simultaneously, you can take inspiration that comes from the clinic and apply it in your research. The expertise and perspectives of physicians and scientists can be quite different, so it’s nice to provide a bridge between the two to benefit patients.

While I was at Pomona, I was on the tennis team. I was incredibly close to my teammates and to my coaches, Ann Lebedeff and Mike Morgan, and they were family to me. Many of my formative experiences in college were with my team. Tennis uses a different type of mental energy, and that allowed me to take a break from studying.

I think a lot of students at Pomona find themselves involved in clubs or community organizations, such as Health Bridges. I’d encourage them to take advantage of these opportunities and find their own little family away from home while they’re at Pomona. After graduation, life becomes more fragmented, and these opportunities are harder to come by. College is a time for students to grow and find the directions they want to go in life.

Julia Foote and I met during our first days at Pomona and continued to live together during our two gap years in Boston. When applying to medical school, I was particularly excited about Harvard Medical School’s Health Sciences and Technology program, which is designed for students who are interested in research and innovation in medicine. The day I got the call from the program director that I had been accepted into HST, I was at work. I was in shock and at a loss for words; I was just so happy and relieved. After hanging up, I immediately called Julia, admittedly even before I even told my family. Fortunately, Julia got her HMS acceptance later that same day. We have been friends for going on 10 years. Now we’re about to graduate from medical school and are excited to continue our careers as doctors together.

Honestly, when I came to Pomona, I didn’t fully know what to expect from a liberal arts college experience. Now that we’re a few years out from graduation, I have a better perspective on the skills and experiences that Pomona gave me—from the tennis team to research to small classes—and how it has prepared me for my career. Pomona helped me learn to be incredibly independent, confident in my own abilities and prepared to tackle challenges in the real world. Nothing feels too big to overcome because of what I’ve already experienced.

Grant Steele ’18

Grant Steele ’18

Undergraduate Major: Biology

Minor: Spanish

Fast Facts:

- Currently a resident in urologic surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital.

- At Pomona, learned to engage at a high level with both science and the humanities.

- Memorable classes at Pomona included Genetic Analysis and a Spanish literature course on the Latin American Boom.

Growing up, I was always enthralled by my mother’s stories of her work as a primary care physician. Whether she was diagnosing and treating complex conditions or helping patients and their families move on to the next stage of life, she seemed to have endless skills she could deploy. I greatly admired her expertise and as I moved through my education, I also began to appreciate the science driving her decisions. Medicine truly seemed to offer the best combination of science and humanism.

At Pomona, I learned to engage with these high-level questions on a deep level. In Jon Moore’s Genetic Analysis class, for example, we focused on one topic each week, such as the underpinnings of Huntington’s disease. We analyzed foundational papers that helped lead to the current understanding of the topic and compared their strengths and weaknesses. I gained an appreciation for the nuances of science that has translated well to the practice of medicine.

In addition to engaging with scientific inquiries, Pomona encouraged this same level of engagement with the humanities. One of my most memorable courses was a Spanish literature course on the Latin American Boom, with Nivia Montenegro. This course gave me a profound appreciation not only for the beauty of well-written literature, but also for the lessons it can teach us on the nature of individuals, society and more.

“I can’t really say why I got into Harvard Medical School. However, I suspect it had something to do with the well-rounded education that Pomona provides and the critical thinkers it produces. “Eager. Thoughtful. Reverent.” In addition to being inscribed on the gates of Pomona, I think those traits describe people who will succeed at HMS.

Looking back—I graduated from HMS in 2023—I greatly enjoyed my time in medical school. I loved being surrounded by curious and hardworking people, just like at Pomona, whether they were classmates, professors or doctors. There were endless opportunities to explore interests and passions without pressure to stretch myself thin.

At HMS, I interacted with fellow Sagehens all the time. We had a built-in community. Now that I’m a busy resident, I particularly find comfort in seeing my fellow Sagehens, both at the medical school and among the other residents at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Near the end of my fourth year at HMS, I did an intensive care unit rotation. It’s known for being intense, both intellectually and emotionally. In a way, it’s the pinnacle of the med school clinical experience. During that month I cared for a gentleman in his 80s that I’ll call Mr. A. He came in with heart failure that progressed to kidney and respiratory failure. From an academic perspective, it was a thrill to finally feel like I could understand the medical complexities and contribute to his care. The more memorable aspect, though, was helping care for his wife, daughters and extended family.

Sadly, it became evident that Mr. A was not going to recover. Our team helped the family through the difficult decision to focus on maximizing his comfort. I emphasized with the family that sometimes the bravest decision is not to continue with aggressive treatments but to know when to stop. He passed away comfortably the next day. I’m proud of our team’s work to help the family embrace Mr. A’s final moments. I’m also thankful for the mentorship, starting with my mother and continuing at Pomona and HMS, that helped me develop these skills that I continue to hone as a urology resident.

Julia Foote ’18

Undergraduate Major: Neuroscience

Undergraduate Major: Neuroscience

Fast Facts:

- Came to Pomona from Jamaica never having visited the campus. Plans to take a medicine residency. Would like to be involved in both patient care and health policy research.

- Enjoys translating scientific evidence into everyday language for patients.

I was born in the United States but grew up in Kingston, Jamaica. At a young age, I saw the difference that a plane ride could make in one’s health outcomes when my mom developed degenerative disk disease. As dual citizens, we were privileged enough to seek a diagnosis and treatment for my mom in the U.S. But seeing the need for broader health-care access in Jamaica inspired me to pursue a career in medicine.

I started medical school on Zoom in 2020, early in the pandemic. But at least I knew Sal [Daddario] and Mary [Zhao] and Michael [Poeschla] and other Sagehens in my class at Harvard Medical School.

After graduating from Pomona, I took two gap years before starting med school. I worked at Massachusetts General Hospital in a group that uses simulation models to evaluate the clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness of various HIV treatments. It was different from the basic science and bench work that I had done at Pomona, but I was able to translate the skills I learned as an undergraduate into a different framework and research modality. Shout-out to Professor Karen Parfitt in the neuroscience department. I was in her lab for three years, and she taught me how to actually conduct research and gave me the confidence to do it.

That has now informed what I want to do in my future career. I’m applying for a medicine residency with a possible subspecialty in cardiology. Thinking more broadly, I’m very interested in health-care utilization and the cost-effectiveness of various treatments and screenings for disease. Right now at HMS, I’m continuing to do health policy research. I’m working to develop a simulation model of heart failure to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of implementation strategies for guideline-directed medical therapies. My overarching career goal is to have a hand in both clinical care and health policy research.

I have found so much meaning working on the medicine floor with patients to form a shared understanding of their care. This past spring I cared for an elderly man who had recently been diagnosed with heart failure and prescribed a number of new medications. He was unsure of what the diagnosis meant for his future but interested in researching his new medications.

I offered him this: “I’m a third-year medical student, so we can learn this together, if you’d like.” He smiled, accepted the offer, and we sat down together and reviewed the results of various heart failure trials. I left the hospital that day feeling both excited and grateful: excited to meaningfully engage with my future patients, and grateful for the opportunity to translate scientific evidence into everyday language.

My very first day at Pomona, in 2014, I met Mary Zhao. Our rooms were side by side in the dorm. We roomed together when we both took gap years in Boston, and we applied to med school at the same time. Harvard has two medical school tracks. Mary applied for the Health Sciences and Technology (HST) track, which emphasizes interdisciplinary research. I chose the larger Pathways track focusing on clinical experience. Only about 30 students a year are accepted into the HST program, so unlike with the Pathways acceptances, the admissions officer can call each accepted student personally. As soon as Mary got the call, she was on the phone to me with the good news.

That’s how I knew that Harvard’s acceptances were coming out. After hearing Mary’s news, I just sat at my desk for an hour, frozen in anticipation. Then suddenly an email appeared on my screen: “Welcome to Harvard Medical School.” I didn’t even open the email. I bolted into a conference room and called Mary. Then I texted my family. My dad FaceTimed me back, sobbing. Harvard wasn’t the first medical school I had gotten into. To my family, though, it was the biggest deal because I’m from Jamaica. Everyone in the world knows Harvard, whereas no one cared about any other medical school that I got into.

I’m extremely grateful to have gone to Pomona. I was a bit apprehensive at first because, being from Jamaica, I didn’t do any college tours. I based my decision entirely on seeing the college’s website. But I sing Pomona’s praises to every high school student that I know who’s applying to college. It was a great experience.

Michael Poeschla ’18

Michael Poeschla ’18

Undergraduate Major: Molecular Biology

Fast Facts:

- Is currently an M.D./Ph.D. student at Harvard, researching bioinformatics and genetics.

- Credits exceptional biology professors at Pomona.

- Studied abroad and worked in a lab at University College London as a Pomona student.

I got interested in the field of biomedical research early on—I liked the idea of a career where you get to continuously learn new things and be part of creating new knowledge that might help people.

Currently, I am an M.D./Ph.D. student at Harvard Medical School. After two years of preclinical medical school classes, I started my Ph.D. in bioinformatics and genetics in 2022. My Ph.D. work is focused on understanding how human genetic variation impacts blood cell production and blood cancers, as well as aging.

I am really grateful for the education I received at Pomona, which was great preparation for doing a Ph.D. At Pomona I was fortunate to learn from exceptional biology professors like Jon Moore, Sara Olson and André Cavalcanti. Their classes, such as Genetic Analysis and Advanced Cell Biology, instilled a deep appreciation for the wonders of biology and inspired me to get involved in doing research to advance human health.

At every step, I’ve had serendipitous connections that ended up having a great impact on me. After I became really interested in research after studying abroad and working in a lab at University College London, a classmate at Pomona told me about research opportunities in Germany. That led me to apply to the Max Planck Institute after I graduated. I had the good fortune to find an unbelievably generous mentor, Dario Valenzano, who agreed to take me on in his lab after just one Skype call. Spending two years in Cologne studying rapidly aging African turquoise killifish was an exhilarating experience that really shaped who I am today.

I’ve really enjoyed living in Boston, and life as an M.D./Ph.D. student is pretty good. I have lots of time to do research, take interesting classes at Harvard and MIT and constantly learn new things. I get paid to take classes and do research—can’t really complain!

I’ve made some good friends here, and I was lucky to start medical school in Harvard’s Health Sciences and Technology program alongside Mary Zhao. She was a classmate at Pomona, and we both played varsity tennis. We were roommates for the first three years of medical school before ending up on opposite sides of the Charles River this year. We still meet up for Chinese or Korean food every few weeks.

My advice to current Pomona students is to enjoy every moment of the experience. I miss Pomona a lot! It is such a great place to explore widely. Take the opportunity to try new things, learn about whatever you might be interested in, and see as much as you can of what’s out there in the world as you figure out what you want to do with your life. I also wish I’d learned to surf and had eaten more tacos while I was living in Southern California. Boston is a great town, but in those areas, it can’t compete with L.A.!

Samantha Little ’20

Samantha Little ’20

Undergraduate Major: Neuroscience

Fast Facts:

- Being part of the Pomona-Pitzer lacrosse team helped prepare her for teamwork in her medical career.

- Finds time even in med school for work-life balance.

- But had to replace Instagram with flashcards!

I’ve always been drawn to science in the classroom, but I am passionate about connecting with and treating people, and practicing medicine is one of the most human types of work a person can do.

One of the most formative parts of my time at Pomona was being a member of the Pomona-Pitzer lacrosse team. Medicine is truly a team-based career, so the experience of playing a sport in college has made it much easier to integrate myself into the different surgical teams in the operating room and medical teams on the wards.

I really enjoyed—and I think I needed—two gap years between college and medical school. It gave me time to define my priorities in life before starting school again. I had a list in my head of my “non-negotiables,” things in my life that I was not willing to give up during medical school.

The idea of med school taking over my life was scary to me before I started. But once I got to Boston and got settled in, I learned how to balance work and life and am happy with the quality of life I have today. I have time to do hobbies like regular exercise that bring me joy, socialize with classmates outside of school and maintain a happy and healthy relationship with my significant other—though I did have to replace Instagram with flashcards!

I ended up coming to Harvard Medical School because I really connected with the people I met while visiting campus, including another fellow Sagehen. I think any school will give you a stellar education. My best advice is to find one where you can picture yourself being the happiest.

I truly love the people I have met at HMS. Everyone is kind, supportive and incredibly passionate about a particular aspect of medicine, and that makes for inspiring energy. And I love seeing other Sagehens! Grant Steele helped teach anatomy to my first-year med school class. Sal Daddario was my near-peer mentor in my pediatric rotation. Both of them were in the Pomona Class of 2018.

Learning to practice medicine can have unexpected twists and surprises. I did a patient interview and physical exam on a woman who, the day before, had received an above-the-knee amputation. I was a bit nervous to talk to her, since I assumed that she would be mourning the loss of her lower leg and foot. When I walked into the room, though, she was one of the happiest patients I have ever talked to. I asked her how she was feeling about her amputation and she said, “Ugh. Good riddance!” She was so excited about this new chapter of her life since her foot had caused her terrible chronic pain.

That experience taught me to challenge my assumptions when I meet a patient. I may have no idea where they are in their medical journey. They may be having every surgery possible to try to save a limb, or, like that patient, they may be happy to get rid of it. I try to bring a blank slate into each patient room I walk into, so I can really listen to their experience.

We try to show them that a holistic approach to education based on rigorous principles is what we think is the key aspect of an education like this one.”

We try to show them that a holistic approach to education based on rigorous principles is what we think is the key aspect of an education like this one.”

What is it about that liberal arts degree that you really value? … that’s exactly what employers want.”

What is it about that liberal arts degree that you really value? … that’s exactly what employers want.”

Maryann Zhao ’18

Maryann Zhao ’18 Grant Steele ’18

Grant Steele ’18

Michael Poeschla ’18

Michael Poeschla ’18 Samantha Little ’20

Samantha Little ’20