With an artist’s flair and a dedication to fairness for South Asian farmers, Sana Javeri Kadri ’16 and her Diaspora Co. are shaking up the spice industry. Photo by Gentl and Hyers. Additional photography courtesy of Diaspora Co.

Black pepper, with its biting heat and piney taste, comes to many of us in the West in grocery store grinders and is used in cuisines throughout the world. Chocolate, with flavor profiles ranging from milky or bittersweet to notes of berries, often is associated with places like Belgium and Switzerland.

Top left, cocoa being processed into chocolate (bottom left). Top right, a man holding a peppercorn, which is dried and milled into black pepper (bottom right).

But CEO and spice merchant Sana Javeri Kadri ’16 and her business Diaspora Co. are here to remind us that the bulk of our spices aren’t native to Europe or America—and their true flavors and colors aren’t what we’re buying in conventional markets. Black pepper, for instance, hails from the steamy shade of the southernmost and very tropical state of Kerala, in India, and can have a more complex, fruit-forward taste, even coming in shades of purple.

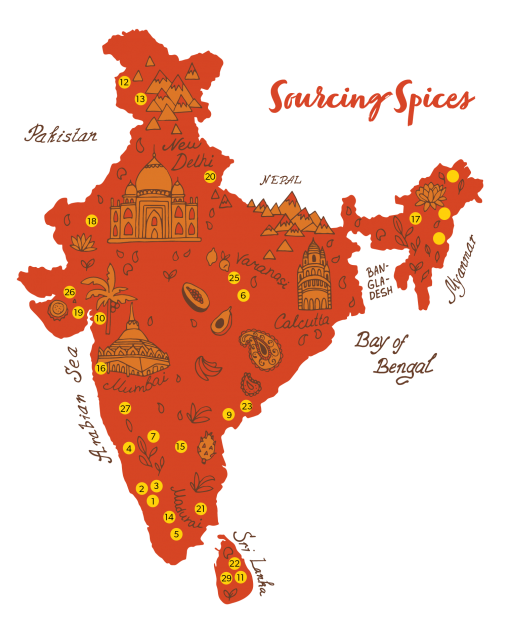

1. Cacao, 2. Mace, 3. Nutmeg, 4. Aranya Pepper, 5. Baraka Cardamom, 6. Bindu Black Mustard, 7. Byadgi Chillies, 8. Chota Tingrai Black Tea, 9. Guntur Sannam Chillies, 10. Hariyali Fennel, 11. Kandyan Cloves, 12. Kashmiri Chillies, 13. Kashmiri Saffron, 14. Kaveri Vanilla, 15. Kudligi Moringa, 16. Madhur Jaggery, 17. Makhir Ginger, 18. Jodhana Cumin, 19. Nandini Coriander, 20. Pahadi Pink Garlic, 21. Panneer Rose, 22. Peni Miris Cinnamon, 23. Pragati Turmeric, 24. Sirārakhong Hāthei Chillies, 25. Sugandhi Fenugreek, 26. Surya Salt, 27. Wild Ajwain, 28. Wild Heimang Sumac, 29. Wild Cinnamon Quills

Javeri Kadri is here for more than a lesson, however. She is set on surprising palates with the taste of fresh top-shelf spices, and she’s determined to disrupt the spice industry by paying a living wage to Indian and Sri Lankan farmers.

Diaspora Co., established by Javeri Kadri in 2017 when she was 23 years old, has made a culinary splash in the industry, the media and home kitchens. In short order, Javeri Kadri was named to the 2021 Forbes 30 Under 30 list for the food and drink industry for her successful entrepreneurship. She and her company have been featured everywhere from CBS Mornings to Condé Nast Traveler, Bon Appétit, Food & Wine magazines and many more outlets. Whole Foods Market recently selected Diaspora Co. to be among 10 startup participants in the Local and Emerging Accelerator Program (LEAP), an initiative that launched last year offering mentorship, education and potential financial support to up-and-coming food and beverage brands. Over the years, Allure and The Cut have even detailed Javeri Kadri’s skincare and haircare routines—further proof of her celebrity spice trader status.

Throughout her time on campus, Javeri Kadri was heavily involved in the Pomona College Organic Farm.

Long before she was a rising star in the spice business, Javeri Kadri was a kid foodie. In nursery school she would go to the kitchen and eat all her classmates’ snacks—apparently without remorse. The running joke in her household was that if 3-year-old Javeri Kadri were kidnapped, she would be promptly returned home due to her insatiable appetite.

Her passion for food, which started as a toddler in Mumbai, inspired Javeri Kadri to study the slow food movement at an international high school in Italy. Then she arrived in Claremont. An art major, Javeri Kadri was profoundly influenced by Pomona College Art Professor Lisa Anne Auerbach and Art History Professor Phyllis Jackson, and eventually creatively combined her interests in photography and food justice.

But on Day One at Pomona, Javeri Kadri fell head over heels in love with the Organic Farm and agriculture. She spent virtually every day there, as a farmworker for the first two years and then teaching farming and cooking.

During her sophomore year, Javeri Kadri took a semester off to study regenerative agriculture and sustainable food systems. This wasn’t just a matter of interest; it was a matter of making a return on her parents’ investment in her.

“There was this feeling for me that being at an American liberal arts college was the greatest privilege of my life and the greatest expense my parents would ever incur,” she says.

Javeri Kadri knew she had to make good on her parents’ sacrifice. So while they never pressured her to pursue a particular major or vocation, they did impress upon her that it was critical she graduate with a clear plan. So during her semester leave she got a job at an urban farm, another job at a bakery, worked at a restaurant and found every single mentor she possibly could in New York. She says she returned to campus with all the tools she needed to start her long-term career journey, which she ultimately describes as telling stories around agriculture and food systems.

Sana Javeri Kadri ‘16, an art major at Pomona, keeps her camera close at hand in her travels. She is photographed here standing in a field on a Kashmiri saffron farm.

As a Pomona junior, she started the Claremont Food Justice Summit, which later turned into Food Week and brought in speakers from all over the country. This was certainly educational for The Claremont Colleges community, but it also was aspirational individually. Javeri Kadri says she networked relentlessly.

In the midst of the self-described hustling, Javeri Kadri also was working on her senior art thesis, which was about the effects of colonialism on food, specifically British colonialism on Indian cuisine. Javeri Kadri’s point of inquiry was chai. Through her thesis, she learned that spices on grocery store shelves are very old and very stale and that the industry doesn’t prioritize freshness or quality, she says. She also learned that spice farmers make almost no money. For at least four centuries, she says, the industry has been built to profit middlemen, not the farmers.

But economics wasn’t the only aspect that disturbed Javeri Kadri. Cultural whitewashing did as well. Situating spices in their indigenous contexts was critical for her.

“If a spice is coming from the hills of northern Kerala, people should know what northern Kerala pepper recipes are and how amazing they are,” she says. “It is partially about right or wrong, but it’s also delicious.”

Local farmers at a floating vegetable market on Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir, India. Photography by Sana Javeri Kadri ’16 on a sourcing trip to visit saffron and Kashmiri chilli farm partners.

“Right,” “wrong” and “delicious” may be shorthand for Javeri Kadri’s philosophy of business for Diaspora Co., which promises that its farmers get a fair living wage and aims to disrupt the industry’s unsustainable farming practices and discrediting of culture, while also supplying fresh, delectable spices.

Origin, equity and—unsurprisingly for an art major—even beauty are paramount principles for Javeri Kadri’s business. Diaspora Co.’s Instagram profile (@diasporaco) and website (diasporaco.com) reveal stunning photography, much of it by Javeri Kadri, and thoughtful narratives.

There are photos of the intricate designs on Diaspora Co.’s vibrant marigold and raspberry-colored tins; a shot of Pahadi pink garlic, with its cream-edged petals, cradled in the hands of a farmer at the harvest in the lush mountains of Uttarakhand in northern India. There are videos to stimulate salivary glands, like a recipe for corn ribs with smoky chili-saffron butter and a chai masala cocktail, which is a combination of Diaspora Co.’s house chai masala, jaggery syrup and a black-tea infused bourbon. Another video traces the production of cinnamon, from tree bark to quill, in Kandy, Sri Lanka. A slideshow depicts a pile of sand’s transformation into a gleaming bronze mortar and pestle. Javeri Kadri, of course, is an installation artist by training, and she jokes this venture started off as one big art project.

“I’m not going to get into business unless I can build it the most beautifully and idealistically as I can. … Is it possible to build the most equitable form of the spice trade and make it beautiful?”

A professional food and culture photographer earlier in her career, Javeri Kadri is the artist behind many of the photos on Diaspora Co.’s distinctive Instagram. Check out other photos @diasporaco.

Evidently, the answer is yes. The art project evolved into a company that works with 140 farmers and pays an average of three to even 10 times over the going commodity price. Javeri Kadri acknowledges that Diaspora Co. spices fall on the luxury end of the spectrum, price-wise. According to a Los Angeles Times writer’s description, the taste also is premium—Diaspora’s Aranya pepper is not just peppery, “but also extra-ripe-strawberry fruity, and with some actual heat on the tongue.”

Javeri Kadri is quick to acknowledge that Diaspora Co. is not perfect, but what she appreciates most is her team and how they keep one another honest, accountable and forever on a growing edge. Her hope for her business is that what is now a luxury for a few will become the standard for the industry at large: better sourcing, better salaries, better spices.

Sourcing is among the most critical ingredients and challenges for their business. Pragati turmeric from Vijayawada in the state of Andhra Pradesh, in southeast India, was the first spice that Javeri Kadri sourced. Diaspora Co., which now sells 30 spices, only launches a spice after rigorous testing and tasting on two continents and once they believe it’s the best of its kind on the market. It took four years to find fennel that met its criteria. The quest for the finest dried mango powder is ongoing.

The transformational effect of Diaspora Co. on its farming partners is astounding, Javeri Kadri says. As the farmers’ wages increase, naturally their lifestyle does as well and there are tangible and significant markers even in the span of six years. After Year One, the farmers may buy a smartphone. After another year, they send their children to a better school. One more, and they are willing to talk about paying their workers more. After the fourth year, they start to think about how they can get similar returns on their other spice crops, since most are growing multiple varieties. Diaspora also has a farmworker fund divided amongst their three oldest farm partners (turmeric, pepper and cardamom farmers) and each farmer receives $7,000. These funds go toward building women’s toilets, establishing medical camps, setting aside land for a kitchen garden for the farmworkers, and other projects.

Diaspora Co. is a small company but for the farmers, it is a mighty one. Since 2019, Diaspora has paid out $2.1 million to 140 regenerative farms. In 2022, the company purchased 16 metric tons of spices. Diaspora started with a modest investment of $8,000 from Javeri Kadri’s parents and the entirety of her tax refund of $3,000. Over the years, it has been supported in part by family, friends and operator angels—angel investors who also are food industry mentors, including chefs and CEOs.

Even deeper than Javeri Kadri’s love for spices is her passion for social justice. It is arguably coded in her DNA. Her paternal grandmother started a nonprofit in the 1980s called Save the Children India (no relation to Save the Children USA), which became a large organization focused on serving underprivileged children and children with disabilities. Javeri Kadri grew up visiting the rural hospital her grandmother built.

“The family business is architecture, but it was also service,” Javeri Kadri says. Her father’s ongoing reminder was that they had great privilege, so much was required of them.

“I grew up upper class in Mumbai. It’s a lot. And then was able to go to the world’s best schools on three continents,” she says. “So how am I going to use that and how am I going to pay that forward?”

By dealing spices—with equity, beauty and, of course, taste.