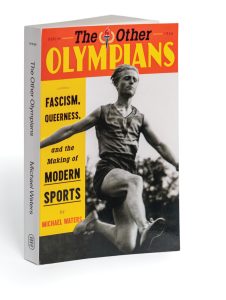

Four years after graduating, Michael Waters ’20 has published his first book, The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports. Released in June ahead of the 2024 Olympics this summer in Paris, Waters’ book tells the story of early trans athletes and the roots of sex testing of athletes in the 1930s.

In 2021, Waters’ senior history thesis at Pomona about placements of queer youth with queer foster parents in New York City in the 1970s was adapted and published in The New Yorker. Since graduating, he has contributed numerous articles to publications including The Atlantic, The New Yorker, WIRED, Vox and The New York Times.

Pomona College Magazine’s Lorraine Wu Harry ’97 talked to Waters about the book as well as his development as a historian and journalist. Answers have been edited for clarity and length.

PCM: How did Pomona train you as a student of history?

Waters: Professors in the History Department taught me the potential of discovery in the past. There are so many stories of marginalized communities out there. They are just harder to find in traditional archives. But there’s a way of doing history where you read against the grain and you look for what’s not there.

What fascinates me about queer history is finding pockets of queer community in these spaces and in these eras before we would expect them. I want to try to scramble this idea of queer history as a linear story of progress. Queer history has never been linear. There are so many surprising examples of acceptance and celebrity and community that existed before World War II, before traditional narratives of queer history, before Stonewall. My work is about finding those lost communities. Where was community, where were queer people coming together and what does that say about us today?

Often what I do is I look through newspaper archives. I like to do search terms related to gender and sexuality and filter for certain eras to see what comes up. There are often stories in those newspaper archives that haven’t bubbled to the popular consciousness today but that were a big thing at the time.

PCM: How did you conduct research for this book?

Waters: It was hard in many ways, but one really lucky thing was finding a short memoir that Zdeněk Koubek, the main Czech athlete in the book, wrote in 1936 in a Czech magazine. It was this rich, 40,000-word manuscript about his life. That solved what would have been potentially insurmountable archival problems, because a lot of his story is otherwise not well-documented.

A lot of the book pulls from different newspaper records, too. For the Olympics, I went to the International Olympic Committee archive and went through some of their 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s correspondence files. Avery Brundage, who’s a big part of the book—he’s an American IOC official—has this huge archive in Illinois, where he saved literally everything, it seems.

To make a book, especially a nonfiction book, sellable, there’s so much luck involved when it comes to sourcing. I couldn’t have done this book if it wasn’t for that source from Koubek’s life. Everything kind of came together after that.

PCM: How did you learn to write so well?

Waters: I hope that’s true. I’ve been writing magazine-type stories for a while now, which is very different from writing a book, obviously. But that muscle was helpful in this process. I started freelancing originally for Atlas Obscura, which is a website that chronicles historical oddities. I started writing for them in 2016. I emailed an editor out of the blue with an idea. That was between high school and college. I’ve been doing something along those lines in my free time ever since. It makes it easier to figure out how to tell history in a compelling way, I hope.

PCM: Were there any things that surprised you as you wrote this book?

Waters: When I first started doing this research, I was surprised how American media received the news of these athletes transitioning gender. When you read those articles from the 1930s, there’s a real sense of curiosity about them and how one could move between different categories of what we would call gender today. Certainly, there were some skeptical stories that existed, and there were others that were quite sensationalist. But even through that, there is this real sense of interest and fascination and, in many cases, acceptance. People accepted that there’s a lot we don’t understand about how gender works, how the body works. There were op-eds from doctors that would say, “This is actually quite normal.” It’s especially illuminating when, by contrast, you look at all of the transphobic coverage in newspapers today.

PCM: What impact do you hope your book will have?

Waters: When it comes to sports today, I hope that the book provides context for the anti-trans and anti-intersex policies that exist at the Olympics. The big thing for me is to show the influence of fascist ideology on these policies. Tracing that history lets us see how Nazi-aligned sports officials originally rammed these policies through. These policies were flawed from the beginning, and that tells us something about them today. We can also see alternate pathways for how sports could have included people of many different genders, if officials had just been willing to have that conversation.

I also hope that the book inspires more researchers to look into queer life in the early 20th century, because there were so many incredible stories that I came across about queer community and gender transition in this era. I hope to bring some extra attention to these stories of real people that have been lost, and then let other researchers take the mantle. I don’t want to have the final word, especially on a story as significant as Koubek’s. But that takes researchers and that takes institutions being willing to fund this research.