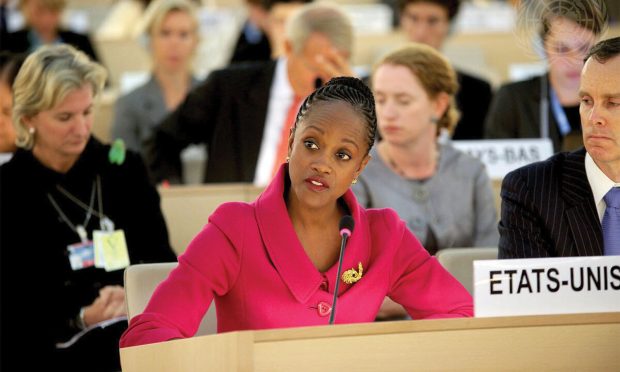

Esther Brimmer, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs, addresses the opening session of the high-level segment of the Human Rights Council. In her statement to the Council, Ms. Brimmer emphasized, among other themes, the protection of freedom of expression, the fight against negative stereotyping, and affirmed the United States’ commitment to the Council.

In the fall of 1981, her junior year at Pomona College, Esther Brimmer ’83 arrived in Switzerland for a semester of graduate-level study in international affairs at what is now the Geneva Graduate Institute.

To say the experience was transformative is an understatement.

Esther Brimmer, then assistant secretary of state for international organization affairs, at 2009 news conference. Courtesy of U.S. Mission Geneva

Brimmer couldn’t have imagined her return to Geneva in 2009—one of many in her career—for what she called “my proudest moment as a diplomat.”

As assistant secretary of state for international organization affairs under President Barack Obama, Brimmer gave the first speech on behalf of the United States as an elected member of the United Nations Human Rights Council.

“We recognize that the United States’ record on human rights is imperfect,” Brimmer said in part. “Our history includes lapses and setbacks, and there remains a great deal of work to be done.

“But our history is a story of progress. Indeed, my presence here today is a testament to that progress, as is the administration I serve. It is the president’s hope and my own that we can continue that momentum at home and around the world.”

An International Career

That semester in Geneva was a springboard to an extraordinary career. Brimmer, now the James H. Binger senior fellow in global governance at the Council on Foreign Relations, has served three appointments within the U.S. Department of State, including her tenure as assistant secretary of state from 2009 to 2013. She also has held numerous other positions in government, academia and non-governmental organization leadership. And as testament to her belief in the value of international study, from 2017 to 2022 Brimmer was executive director and CEO of NAFSA: Association of International Educators, a professional association dedicated to international education with some 10,000 members in more than 160 countries.

Acquiring a broader global view has value beyond career preparation, she says, and a college student doesn’t necessarily have to cross a border to gain it.

“There are many different ways in which students can engage in international education—studying abroad, studying international issues at home, getting to know international students,” Brimmer says.

“But one of the important things in being able to study outside of one’s home country is to be able to get insight into how other people around the world view the important aspects of life—being a human being and the important aspects of the world around us, what the issues are and how they look different from different parts of the world. That information can inform all sorts of activities in life. You do not have to just specialize in international relations as a career—much as I would advocate people doing that—in order to benefit from international education.”

A Common Language

Arriving in Geneva, Brimmer at first mixed mainly with other students from Pomona or in the same program. Then she began classes with graduate students from around the world. The French she had studied at Pomona was not only one of the four national languages of Switzerland, she discovered, it was also a lingua franca—a common language that could be spoken among people who did not speak each other’s first languages or who easily switched among multiple languages.

Geneva, the second-largest city in Switzerland, is the European headquarters of the United Nations and the international headquarters of the Red Cross.

“The professor might be replying to you in French, but you could ask your question in English or French,” she recalls. “It was impressive to see the range of languages that the students had already studied by the time they got there. Their facility with multiple languages was quite eye-opening. For some, French and English were their second or third languages.”

The agility Brimmer developed in French—once known as “the language of diplomacy” and still an official language of many international bodies despite France’s decline as a superpower—has been an asset throughout her career.

“I used to remind students that, let’s say you’re interested in security issues and you want to go work for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, you actually have to have French as well as English in order to be on the international staff at NATO,” she says. “It’s true in the United Nations system, but it’s also true about other places as well, where languages are going to help get you the job. International language ability can be quite useful, even if that’s not your specialty, because you’re able to work with colleagues from other countries.”

Brimmer has watched with dismay as some colleges and universities have eliminated foreign language requirements altogether and others have modest standards. For instance, in some University of California and Cal State University programs, students can fulfill a requirement without taking language in college—simply by completing three or four years of a foreign language in high school with a C- or better.

“It is absolutely crucial to understanding other societies,” Brimmer says. “We as human beings express our ideas, thoughts and feelings through language. And then in order to understand these ideas, we need to understand them in their own languages. I’ve been deeply disappointed to see institutions—recognizing they may have their own challenges—but institutions making a short-term economic calculation and missing the long-term implications of what they’re doing. I would want to see language study expand in the United States.”

Strolling the streets of Geneva, Brimmer began to see the news of the world through a new prism.

“One of the things was reading newspapers and numerous news magazines from a different perspective: Remember, the Cold War was still in existence,” she says. “And I remember walking down the street and we saw a television in a window and I thought, oh, something’s going on. Seeing international events from other perspectives was important.”

Basking in Geneva’s café culture, Brimmer discussed issues of the day with older, more worldly graduate students. “They were probably in their mid-20s. And that also helped give me a better sense of the perspectives of students in different places, but also just the perspective on debates. I wasn’t a big coffee drinker, but the opportunity to discuss things from another point of view was interesting. As an American, people always want to give you their view of American foreign policy. Irrespective of whether you say, ‘I’m not personally responsible for it,’ everyone’s giving you an earful. But it’s important that you get that earful and that you begin to explain your views and where you agree and disagree.”

Our Interconnected World

Being exposed to the tutorial system in Geneva—teaching based not on lectures but on deep conversations among very small groups of students and an expert on the subject—also contributed to Brimmer’s decision to go to Oxford University in England after graduating from Pomona. She earned a master’s degree and a doctorate in international relations at Oxford, completing her work in 1989.

Geneva—home to more international organizations than any city in the world and the headquarters of many agencies of the U.N.—has remained special to Brimmer throughout her career.

In 2000, she returned for several weeks as a member of the U.S. delegation helping to negotiate a U.N. resolution on democracy as a fundamental human right. Instead of arriving as a college student, she arrived with her husband and 3-year-old son.

Later, as assistant secretary of state for international organization affairs, the U.S. mission to U.N. organizations in Geneva was her bureau’s largest post.

In addition to government roles, Brimmer has had an extensive academic career as a professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and as the first deputy director and director of research at the Center for Transatlantic Relations at the Johns Hopkins University’s Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies.

In her role at the Council on Foreign Relations, which she has been a member of since 1991, she is writing a book about the necessity of better governance mechanisms to manage expanding human activities in outer space. She also coordinates the work of the Council of Councils, which brings together international affairs research organizations from 24 countries for policy analysis and discussion.

At the State Department, in addition to her role as assistant secretary of state for international organization affairs, Brimmer served on the policy planning staff from 1999 to 2001 and on the staff of the undersecretary for political affairs from 1993 to 1995.

The world she studied as a college student is much different than the one we live and work in now, she says. So many more industries and professions than ever before are interlocked with global concerns.

“It has been striking to realize how much more our lives intersect and interact compared to 40 or 50 years ago—or even 30 years ago,” she says. “Whatever products we use, there’s a good chance that they come from somewhere else in the world. The food we eat, some comes from our own countries and some from the rest of the world. On a daily basis, we depend on not only the trade of goods but also the trade in services, and we benefit from worldwide supply chains. The rapid movement of communications and technology are part of the impact of technology on our daily life. And that means that we are aware of what’s going on in the rest of the world, and the rest of the world actually affects us.

“Students will find that they may have jobs—even if they’re working in the United States—where the companies they work for are part of global companies or receive crucial components for what they’re producing from elsewhere, and that has all intensified over the past 30 years. To understand our daily lives, we do have to have that deep understanding of the world beyond our shores.”

Studying abroad has inspired many a student to pursue an international career, sometimes as a foreign service officer.

Here are just two examples among Pomona’s increasing number of prominent career diplomats.

David Holmes ’97, then posted in Ukraine, arrives for questioning as part of the 2019 impeachment inquiry into President Donald Trump. REUTERS/Yara Nardi

I had never been abroad at all; it was my first time traveling outside the United States, ever. And it got me interested in foreign affairs for the first time.

David Holmes ’97

Deputy Chief of Mission

U.S. Embassy in Budapest, Hungary

Studied Abroad at University College in Oxford, England

I first learned about the Foreign Service during that semester and became very intrigued by the idea of a career that would allow me to serve my country and see the world. I don’t think there is any way I would have become a diplomat without that experience.

Eric Kneedler ’95

U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of Rwanda

U.S. Embassy in Kigali, Rwanda

Studied abroad in Strasbourg, France