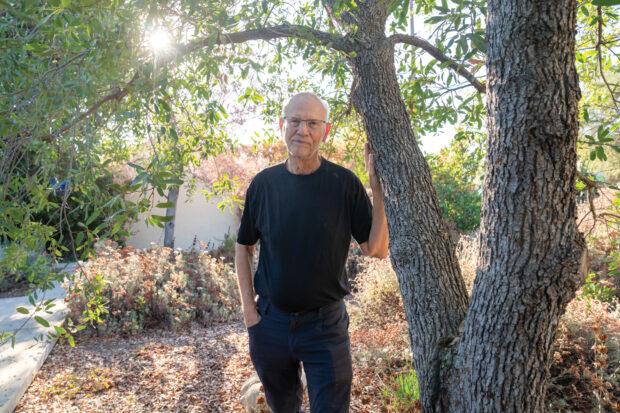

Miller in his backyard in Claremont, where he’s reintroduced Indigenous flora such as coastal sage biota, deergrass and an Engelmann oak.

Indigenous Grounds

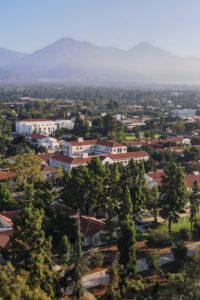

2016: If you’re tall enough, and I’m not, you could peer out of the large, north-facing, four-pane window in the Digital Humanities Studio on the third floor of Honnold/Mudd Library and gaze on a striking tableau. In the deep background are the chaparral-cloaked, rough folds of the San Gabriel foothills that rise to Mount Baldy, the range’s visual apex.

Pull your eyes down to the foreground and a different view comes into focus. You’re looking at the Harvey S. Mudd Quadrangle, although few passersby see its fading metal name. They are on their way to somewhere else. Above that, what catches your vision are the towering stone pines and eucalyptuses, then a green sweep of lawn, establishing the x-and-y axis filled with other geometric shapes. Sidewalks radiate out at right angles from the library connecting pedestrians to Dartmouth Avenue on the west. Stately Garrison Theater is to the immediate north, and to the east, McAllister Center, and Scripps and Claremont McKenna colleges. Nothing is out of place. All grows according to plan. This built environment tightly structures the spatial dimensions of how we experience it.

1901: Fast backward 115 years, a difficult act of imagination that historic photographs can stimulate. Consider a black-and-white photograph shot at the corner of what is now College Avenue and 7th Street, roughly a block south of Honnold. The mountains are vastly more prominent in this more unstructured terrain. The dirt road barely intrudes as your eye is caught first by the snow-capped high country.

The Tongva call this rough ground Torojoatngna, the Place Below Snowy Mountain. It was carpeted with an apparently untrammeled coastal sage ecosystem. In the flatlands, there was buckwheat, sages, ephemeral wildflowers and grasses. The washes and creeks sustained oaks and sycamores. Rock-littered, with not a lot of shade, the landscape was open, capacious. There were even herds of pronghorn antelope. The Tongva and other Indigenous Peoples of Southern California used fire and other tools to manage resources that they wished to extract, including material they invested in their rituals and ceremonies, and that provided food and shelter. Notes biologist Paula M. Schiffman, “By manipulating the mix and abundance of the native plant and animal species present in the ecosystem, the Tongva were able to exert control over the vertical structure of the region’s vegetation and over a diversity of natural processes.”

This Indigenous landscape was more rapidly and enduringly modified when Spanish and later Mexican settler-colonists ran vast herds of cattle, sheep and goat in California’s inland valleys. In 1817, Rancho San Rafael in the present-day San Gabriel Valley—a mere 20 miles to Claremont’s west—had nearly 2,000 cattle and hundreds of horses. Multiply those numbers across the region and it is little wonder these herbivores, in Schiffman’s words, quickly became the “dominant organisms” that allowed them to “govern the region’s ecological processes.” Converting coastal sage into grassland, as happened in what is now Pomona Valley, was a reflection of their dominance.

Both the Indigenous and Spanish/Mexican settler-colonist managed landscapes in turn were buried beginning with the post-Civil War Americanization of the region. The late 19th- century arrival of the railroad, and the land speculation and town-building schemes that followed, produced hardened roadbeds, gridded streetscapes, and a series of Victorian buildings that constituted Pomona’s early campus. Since then, The Claremont Colleges have constructed an environment that signals its distance from that earlier time and place. A plaque bolted in Pomona’s Smith Campus Center cheers the ecological conversion that began in the late 1880s: “the clearing away of underbrush, and the planting of roses and other flowers about the building, with an oval lawn in front … forced back the jackrabbits and rattlesnakes.”

2021: What would it take to reimagine the traces of that earlier biome? How might we peel back what the bulldozer flattened, shovel dug in, and the rake groomed? How might we re-see what we have rendered invisible? To make the past, present?”

Start with a trowel. It was the initial symbol of the student-led Ralph Cornell Society devoted to re-engaging with native plants. In the early 2010s, the organization collaborated with the college Grounds Department to plant sage, deer grass, baccharis, and buckwheat in place of grass, a re-indigenizing that dovetailed with campus water-reduction commitments. The department also reintroduced the endemic Engelmann oak, which had been logged out of the region a century earlier.

Often on my morning walks I’ll swing through campus to pay my respects to some of the more than 30 trees that add to the biodiverse canopy, flourishing in their native soil.”

These are small steps, to be sure, but they matter. Ethnobotanist and Tongva elder, the late Barbara Drake, made that case explicitly through her establishment of the Tongva Living History Garden, which has been an inspiration to many students and faculty.

These are small steps, to be sure, but they matter. Ethnobotanist and Tongva elder, the late Barbara Drake, made that case explicitly through her establishment of the Tongva Living History Garden, which has been an inspiration to many students and faculty.

This was among the influences that led my wife and me to transform our quarter-acre suburban lot one mile west of campus. When we purchased the home in 2009, we ripped up the St. Augustine lawn, and with the help of landscapers began to reintroduce coastal sage biota. Initially we planted bunches of deer grass as an evocative play on the now-departed sod; in the back, an Engelmann oak. While lizards loved the cover the grass provided, few other species did. So, as a second draft, we thinned out the long-stemmed grass, and planted different varieties of ceanothus, bitterbush, and buckwheat, and a Channel Island poppy and cherry. Clematis and morning glory are inching up the wooden fence that frames the backyard, and even a prickly pear refugee has taken root. Someone had tossed a pad over the weathered fence, and I troweled it into place. It has now stretched up and out, catching the sun’s rays.

On a recent afternoon, as I picked my way through the aromatic spring growth, jackrabbits and lizards scattered. An Anna’s hummingbird, like a sewing machine, darted around a blue-flowered Cleveland sage, and resting on a leaf while a pair of monarchs twirled into the air above, a mourning cloak. Chattering bushtits picked their way through oak and paperbark.

Home.

This second piece by Professor Miller spotlights Pomona’s two LEED Platinum dorms, first unveiled in 2011. The College has continued to make key strides in sustainability, with goals by 2030 to reach carbon neutrality and reduce its energy emissions 50 percent. Since 2014 Pomona has reduced its water use 45 percent, diverted waste at a rate of 52 percent.

Code Green

What do buildings mean? How do their volume, mass, and detail convey their subject and significance? How do their materials signal what we should see and think about their form and function? Should these structures stand for something?

The U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) believes so. Since its founding in 1993, the nonprofit has been a relentless promoter of the idea that a building’s design should be as sustainable as possible, and that sustainability is a key index of its value and meaning. In 2000 USGBC created the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system, an incentive-based metric that has become a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval for architects and developers.

LEED serves as a way to keep score—the more points a structure earns toward certification, the more lustrous the medal bestowed. While there’s nothing wrong with securing Silver or Gold, Platinum is the ultimate benchmark, a shining example of how the construction industry might help make the world a more habitable place.

Or not. LEED’s many critics are wary of the system’s low bar for certification, arguing that it asks too little of its applicants, offering instead a grade-inflated set of outcomes that undercuts their value. Critics are also skeptical about LEED’s failure to require postconstruction assessment of how certified buildings function: are they as good as advertised? As efficient? As low impact? An even greater lack in the rating is an analysis of how people interact with these certified buildings in real-time. All that glitters is not gold. Or platinum.

Yet the debate is healthy, especially if it compels producers and consumers to ask sharper questions about the built landscape we inhabit, about why it looks, feels and operates as it does. I contributed a small bit to this larger discussion when I spoke at the dedication of Pomona’s two new dormitories in 2011, shortly after they achieved the highest level of LEED certification. They earned it, too; they’re not fool’s gold.

The college takes a lot of pride in these buildings and has posted online an extensive list of their more remarkable attributes. I want to point out one that speaks to my inner wonk—stormwater control. Hardly as sexy as the array of solar panels, lacking the cachet of the green roof and garden, and not nearly as cool as the energy efficiencies that are built into the halls’ every design element, the stormwater system is arguably more revolutionary.

To understand why, imagine a single raindrop hurtling down during one of Southern California’s furious late-winter storms. The moment it hits the ground, according to those who have engineered the Los Angeles basin since the late19th-century, it should be captured as quickly as possible behind a dam or in a ditch or culvert, then swiftly channeled into the concrete-lined Santa Ana, San Gabriel or Los Angeles rivers before being flushed ignominiously into the sea.

The construction of Pomona’s LEED Platinum dorms kicked off a decade of sustainability-minded initiatives.

Some key numbers: The Sontag & Dialynas Halls

- 36% less water use due to native, drought-tolerant landscaping and low-flow water fixtures

- 50% less energy use thanks to high-efficiency energy systems and solar panels

- 14% of the buildings’ energy comes from rooftop solar PV panels

- 2,000 gallons of water heated by a solar-powered system for showers and handwashing

- 100% of on-site rainfall captured to recharge the underground aquifer, at a rate of 7+ feet per hour

This complex system, designed to prevent flooding, has wreaked havoc with riparian ecosystems, destroying the once-robust regional runs of steelhead trout. It also has severely limited the capacity of nature to replenish local groundwater supplies—and we have compensated for this loss by expropriating snowmelt from as far away as the northern Rockies.

Pomona’s new dorms embody a smarter, locally framed approach. Any precipitation that falls within, or flows through, their catchment area will be retained onsite, and filtered down to a large underground detention basin in the alluvial wash that runs along the campus’ eastern edge. There it will slowly percolate into the aquifer, recharging the Pomona Valley’s groundwater. In so doing, these dorms benefit and befit their environment.

Yet will they be as integrative as human habitats? How will generations of students occupy them and make them their own? How will they respond to these buildings that teach sustainability every time they flick a light switch, open a window, or flush a toilet, but that also require their active participation to ensure its realization?

Pomona has asserted that sustainability is integral to its modern mission. One mark of its commitment has been the establishment of a Sustainability Integration Office—the middle word is of prime importance—that inculcates sustainable concepts into new construction and the rehabilitation of older facilities and infuses them into the college’s curricular goals and extracurricular activities.

The community must measure the steps it has taken to fulfill its convictions. That includes using intellectual tools and analytical methodologies to evaluate the very buildings in which so many abide and work. However limited, this rigorous self-examination is not just an academic exercise. Whatever the results, the evaluations will help us calibrate the human capacity to sustain ourselves on this planet of swelling population and finite resources.

Such calibrations may be especially impactful at the local level. How apt, then, that my students’ probing analyses of sustainability as fact and fancy—like the munificence of the donor families that made these two dormitories possible—is fully consistent with Pomona’s century-old charge to graduates: “They only are loyal to this college who, departing, bear their added riches in trust for mankind.”

With these dorms and other campus sustainability efforts the College has reframed that sense of individual social obligation, acknowledging that as an institution it too has a responsibility to redeem its pledge.