Alison Rose Jefferson ’80 stands in the permanent public art sculpture A Resurrection In Four Stanzas by artist April Banks in Historic Belmar Park in Santa Monica. Photo by Jeff Hing

A grassy park known as Bruce’s Beach at the edge of the Pacific landed at the center of the national debate over reparations last year. Los Angeles County deeded the two oceanfront lots next to the park to descendants of Willa and Charles Bruce, the Black couple who lost their thriving resort there to a racist land grab a century ago.

Upcoming Exhibition

Black California Dreamin’

Curated by Alison Rose Jefferson

California African American Museum, Los Angeles

August 5, 2023–March 31, 2024

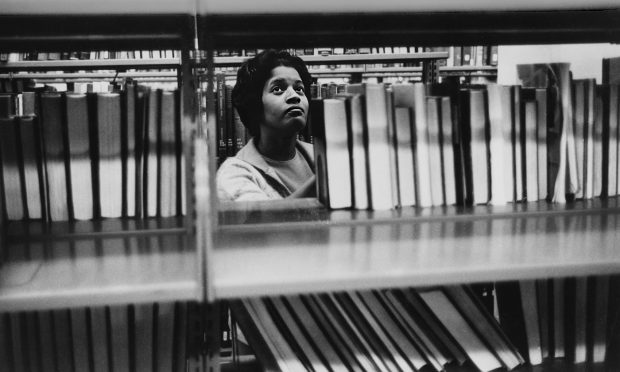

To historian and author Alison Rose Jefferson ’80, who chronicled the history of Bruce’s Beach in her 2020 book, Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era, what happened in Manhattan Beach is a significant example of how the concept of reparations in America has evolved, and of the power of reclaiming stories. But it is only one story. Many more can be found along Southern California’s famous coast, and Jefferson has played a key role in uncovering them.

A little more than 10 miles north of Bruce’s Beach is what remains of the historic Belmar neighborhood in the Ocean Park area of South Santa Monica.

The two lots that formed the Bruce family’s oceanside resort—now the site of an L.A. County lifeguard facility—lie just west of the grassy park that was renamed Bruce’s Beach in 2007.

On a windy weekday, Jefferson walks the streets of present-day Ocean Park at Fourth and Pico, where a lively Black neighborhood stood from the early 1900s to the 1950s. The Belmar Triangle was one of three neighborhoods in South Santa Monica that made up this small community—only about 300 residents in 1920—but here Black families embraced the beach life, raised children, worked, danced, worshipped nearby and called the area theirs.

Today, nothing is left of the La Bonita Café and Apartments, the Dewdrop Inn and Cafe, the Arkansas Traveler Inn or Caldwell’s Dance Hall. In the 1950s, the city of Santa Monica wanted a new civic auditorium, courthouse and a 10 Freeway extension. Claiming eminent domain, the city tore down Black and other marginalized communities’ businesses and cited residents’ houses as unsafe in order to burn them down. Most of the population dispersed, finding more welcoming neighborhoods in areas such as a Black Santa Monica enclave 20 blocks inland, the Venice area and South Los Angeles.

Bay Street Beach in Santa Monica, shown here in 1926, was a gathering place for Black friends and families from the 1920s to 1960s and was sometimes called “The Inkwell.”/L.A. Public Library

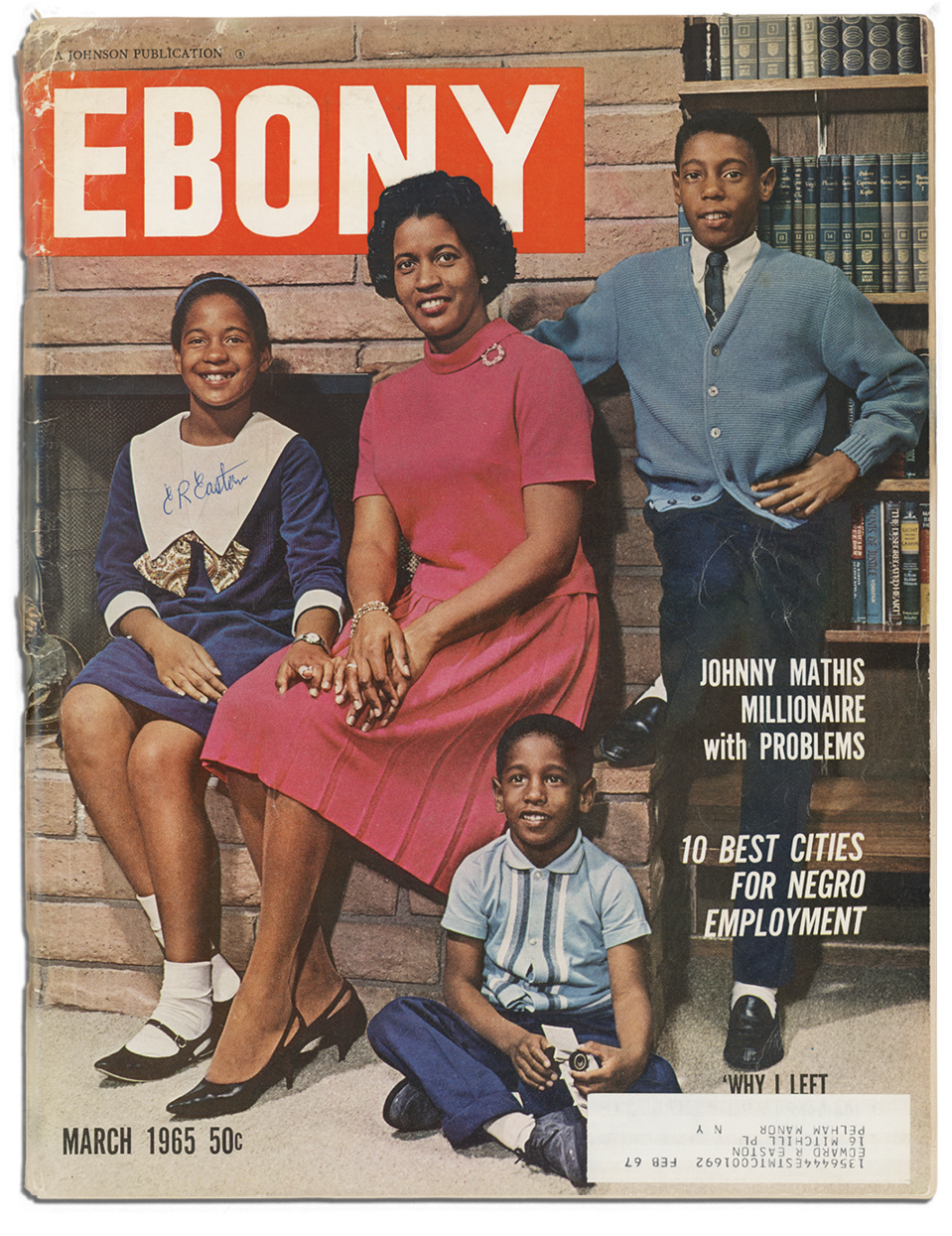

In her book and in the upcoming exhibit Black California Dreamin’ at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, Jefferson reveals the histories of Bruce’s Beach, South Santa Monica and other Black leisure communities in Southern California that have been erased. Lake Elsinore in Riverside County, a bucolic retreat from the city enjoyed by Black Angelenos, was described as the “best Negro vacation spot in the state” by Ebony magazine in 1948. The Parkridge Country Club in Corona was whites-only when it opened in 1925. But its white owner soon ran into financial trouble and controversially sold to a syndicate of Black owners in 1927, after which Parkridge was called L.A.’s first and only Black country club. In the Santa Clarita Valley north of Los Angeles, a resort community developed in the 1920s named Eureka Villa, later called Val Verde, became known as the “Black Palm Springs.”

There is so much forgotten history that the first step of reparations, Jefferson contends, is learning the stories and accepting the past, no matter how difficult that is.

“[In order to] incorporate these stories into our collective thinking, our perception, you first have to be exposed to them,” she says.

Repairing Injustices

A disastrous first attempt at reparations by the U.S. government came in 1865 as the Civil War neared its end, when freed slaves were promised what became known as “40 acres and a mule.” The government eventually reneged on the program and Southern white landowners, not Black families, received much of that “promised land.”

For much of the last 70 years, Jefferson says, one focus of reparations was on educating Americans young and old about the wide-ranging stories of Black Americans, though even that has come under fire recently, particularly in Florida.

“African American historians and people who have been African American allies had been pushing for a much broader narrative to be presented to the public through American history classes in college, high school and grade school and through public venues like museums,” Jefferson says, noting that the 2016 opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., “helped make people much more aware of stories that they didn’t know about.”

Reparation Terms

The big umbrella of reparations covers five main arrangements: compensation, restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition.

Compensation is cash payments given to recipients, whereas restitution is reversing a historic wrong such as returning land or housing.

Rehabilitative reparations include covering costs for mental health, medical, legal or social services.

Satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition are about policy reform, such as removing legal slavery language from state constitutions, public apologies from officials, memorials and other public acknowledgments of specific historic wrongs.

Now there is a broader cry for reparations. Jefferson cites many factors: the 2020 social justice movement (driven by the murder of George Floyd, the killings in Ferguson, Missouri, and other racially motivated incidents), a pandemic that presented people with time to research their own history, and young Black Americans sharing personal stories via social media. “Don’t forget that Barack Obama was elected president,” she adds.

Across the country, government leaders are beginning, once again, to more seriously grapple with how to address the generations of injustices experienced by Black Americans. Reparations are complex, can take many forms (see box at right) and may be politically volatile. There is no “one size fits all,” experts agree.

In 2020, California became the first state to create a reparations task force, and the cities of San Francisco and Los Angeles soon followed by naming reparations advisory committees. Although California entered the Union as a free state in 1850, some people were brought to the state as slaves, and local and state governments continued to perpetuate systemic racism against Black Californians for generations through employment discrimination, displacement of communities and discriminatory educational funding, inhibiting their ability to develop wealth and social mobility.

Some economists initially estimated the potential cost to California for reparations at a staggering $800 billion, and one proposal in San Francisco called for $5 million payments to every eligible Black adult in the city. Ahead of a July 1 deadline to deliver recommendations to the legislature, the state reparations task force instead proposed cash “down payments” of varying amounts to eligible Black residents, which would have to be approved by the legislature and signed by the governor. Elsewhere, the city of Palm Springs, facing a claim for $2.3 billion in damages for the actions of city officials in the 1950s that uprooted Black and Latino families in an area known as Section 14, also is debating a reparations program.

Outside of California, other efforts to acknowledge the past and offer financial restitution are appearing. A program in Evanston, Illinois, is distributing payments to a number of Black residents who faced housing discrimination before 1969. In Asheville, North Carolina, where many Black people lost property during the urban renewal efforts of the mid-20th century, the city has designated more than $2 million toward “community reparations,” such as programs to increase homeownership and business opportunities for Black residents.

These are a handful of examples, Jefferson says. “But it’s a start. We are closer to the possibility of national reparations than in any time in history.”

Recovering History

Woman and small child at Bay Street Beach in 1931./L.A. Public Library

In Southern California, the return of the deed to the two lots that had formed the Bruce’s Beach resort to family descendants was a harbinger of other efforts, and it started with activists who heard the story and wanted justice for Willa and Charles Bruce. The Bruces migrated to Southern California from New Mexico in the early 20th century, and in 1912 Willa Bruce purchased the first of the family’s two lots in Manhattan Beach. Over the years they created a seaside resort for Black Americans complete with a restaurant, bathhouse and space for dancing. But the city council, influenced by the Ku Klux Klan and racist white community members, condemned the Bruce property and that of other African American property owners in the small enclave that had grown up around their business, citing eminent domain to build a community park. The Bruces’ and other Black property owners’ buildings were destroyed in 1927 for a park that did not appear for decades, and owners were paid a fraction of what the beachside property was worth.

Still, less than a year after widespread coverage of the July 2022 ceremony marking the return of the deed to the Bruce descendants, the family sold the property back to L.A. County in January 2023 for $20 million. The move was controversial, but the beachfront land—now used as a lifeguard training facility west of the grassy hill—is not zoned for private development and the descendants had been leasing it back to the county for $413,000 a year. What the family will do with the money is unknown, but Jefferson hopes some of that restitution will be used for community programs in Southern California to encourage young people to head to the beach and learn its history.

Today, the legacy of Bruce’s Beach clings more tightly to its past. “We have to keep telling the story,” Jefferson says. “This story is not over. There are still things we don’t know [about] what happened in Manhattan Beach. There are 35,000 people who live in Manhattan Beach and less than half a percent are of African American descent. So that tells you a legacy. But we also had the legacy of these Black pioneers, the Bruces and the other property owners and the visitors who were going down there who were striking out to enjoy what California had to offer, and to potentially develop their own dreams of property ownership or other things because they were inspired by going to this particular beach.”

Anthony Bruce holds up a certificate of the deed as the family property taken by eminent domain in the 1920s is returned to descendants in 2022.

As she walks the breezy streets, Jefferson explains how the city of Santa Monica reached out to her in 2019 after the California Coastal Commission required an educational program to address the erased Black histories of South Santa Monica as a new park was being developed. She helped create interpretive signage there as part of what became the Belmar History + Art project in the new Historic Belmar Park, located where Black and other marginalized communities once resided. In 2020, the permanent outdoor exhibition was unveiled—colorful signs with historical narratives, along with a bright red sculpture in four pieces resembling the frame of a house. A Resurrection in Four Stanzas was created by Los Angeles artist April Banks, inspired by the people whose homes were destroyed due to urban redevelopment and by a photo of white city officials burning down a shotgun-style house in 1953.

Surrounding the new sports field, the walking path features 16 panels that tell the history of notable individuals—business leaders, doctors, pastors and other Black community members—accompanied by black-and-white photos. A map notes important nearby sites and buildings that still stand, such as the 1905 Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church and the Murrell Building, built by Santa Monica’s first Black mail carrier and also, for a time, the office of the first Black doctors in the area.

Jefferson knows all their stories by heart, many of them told to her through firsthand reflections. From the beach, she stops and points east to the big hill on Bay Street. “Look up at the top,” she instructs. Then she swings around for a straight view of the shimmering ocean before her. “Who could resist this?”

Alison Rose Jefferson ’80 points out local historic sites as shown on one of the panels she designed for the Belmar History + Art project.

Walking down to the beachfront, Jefferson explains that the beach at the end of Bay Street—marked “COLORED USE” on one 1947 map of the era—was another hub for Black Angelenos in the early 20th century to enjoy the sun and sand. It was not without conflict. Casa del Mar, the nearby white-owned beach club, claimed only their members could use the beach in front of the club and built a fence in the sand.

“So [Black beachgoers] found a place where they were less likely to be harassed,” says Jefferson as she walks over to a bronze plaque that recognizes the beach in front of Crescent Bay Park as “The Inkwell,” a controversial name given to it by whites. For years, this destination offered Black residents access to the joys of living in Southern California.

As she looks to the ocean, Jefferson considers her role, doing what she can to “push forward the storytelling.” Among her many endeavors, she has been working with the Santa Monica Conservancy, Heal the Bay and other groups for the last 15 years, facilitating programs on the beach and introducing kids to the history of this area; sometimes they get a surfing lesson and learn about an early Black and Mexican American surfing legend named Nick Gabaldón.

“Education is so important,” says Jefferson. “I want young people to know that they have the opportunity to tell the stories themselves as well. You first need to have that education to build your knowledge base.”

Sometimes, that means heading down to the beach on a sunny Southern California day—Bruce’s Beach in Manhattan Beach, Bay Street in Santa Monica and others—to learn what history has been washed away with the sand.

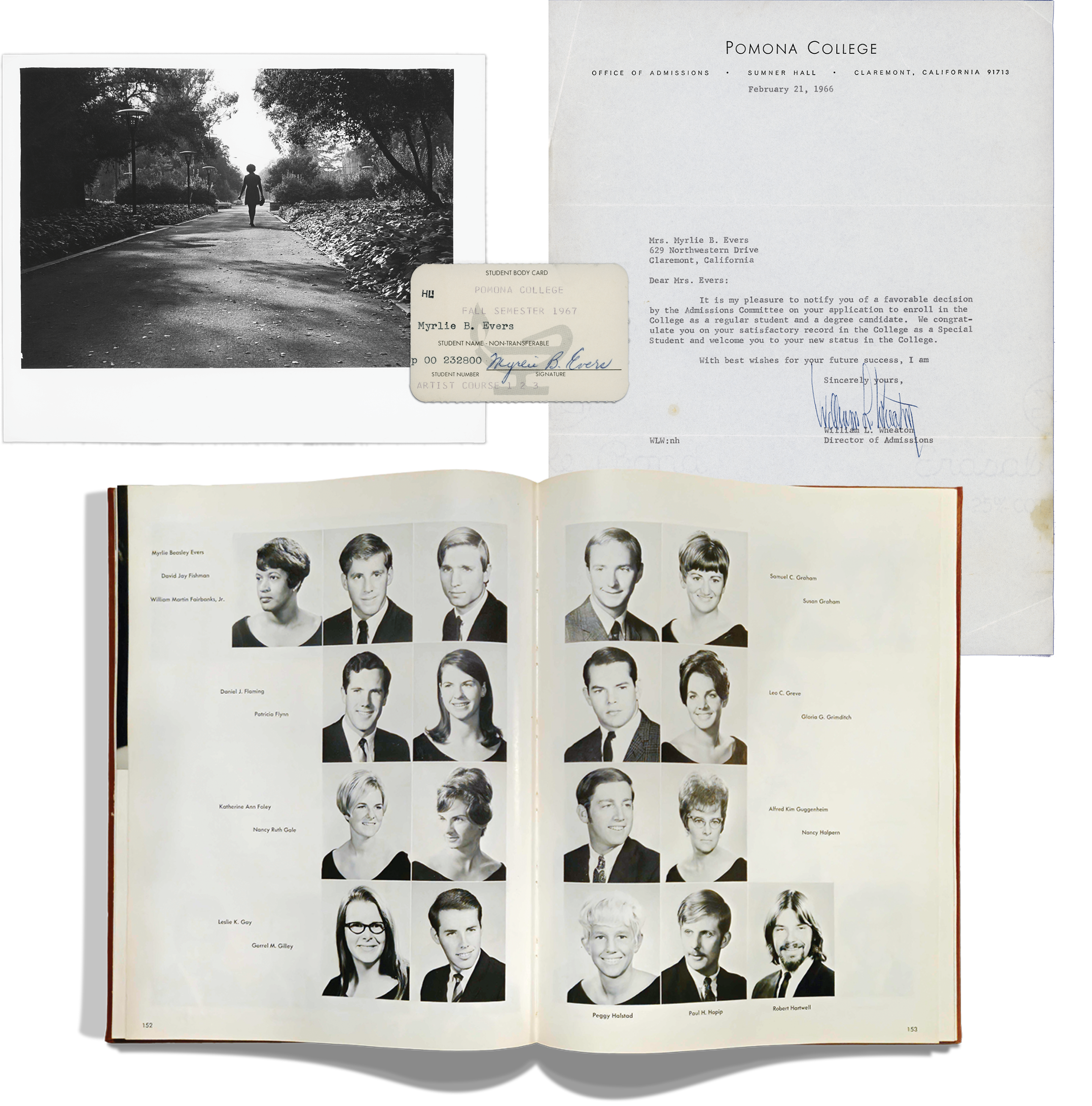

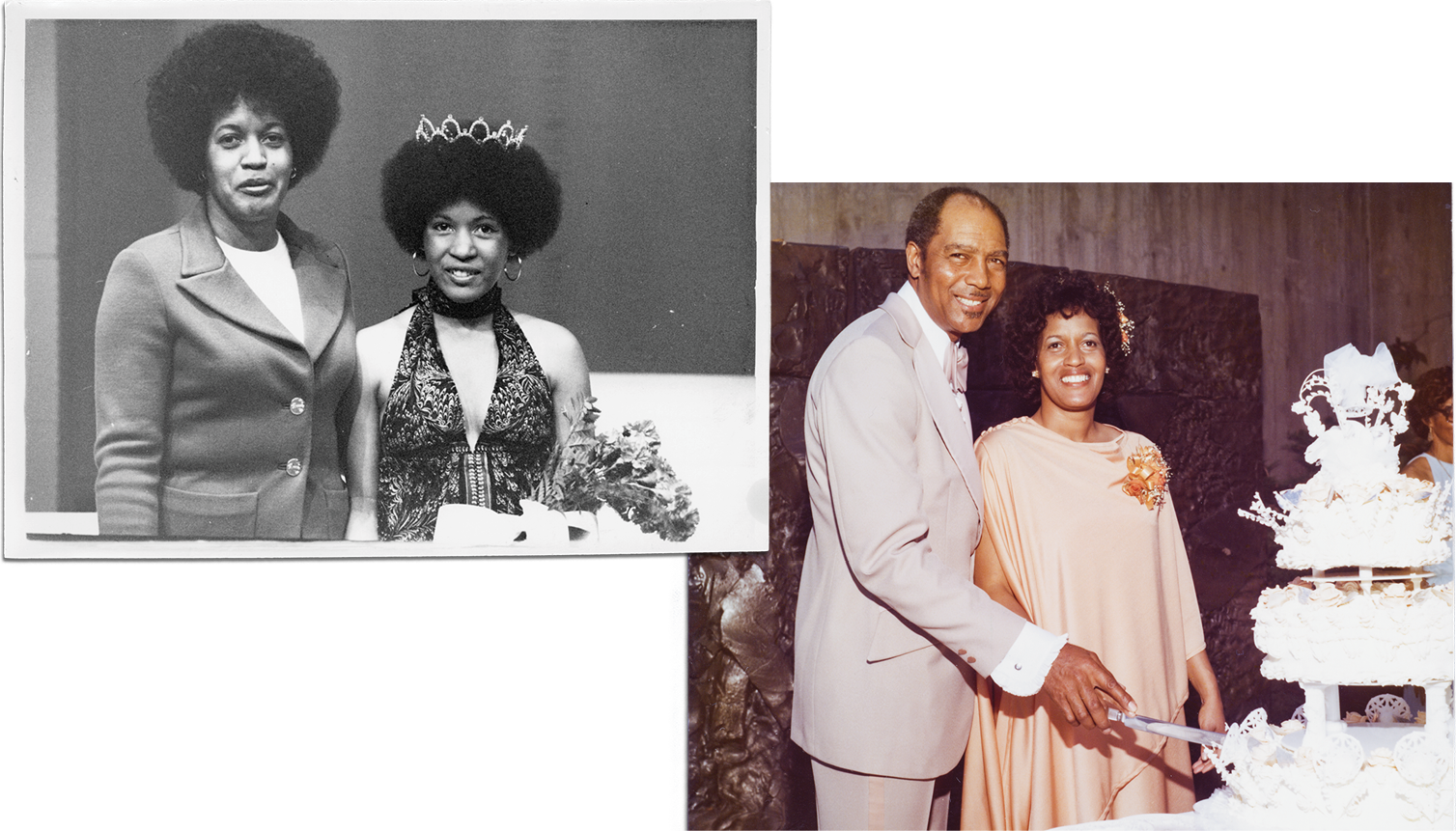

Others at Pomona apparently agreed. Brooks won the Ted Gleason Award, given annually to the student who made a warm-hearted contribution to the community life of the College through traits such as sympathy, friendliness, good cheer, generosity and, particularly, perseverance and courage.

Others at Pomona apparently agreed. Brooks won the Ted Gleason Award, given annually to the student who made a warm-hearted contribution to the community life of the College through traits such as sympathy, friendliness, good cheer, generosity and, particularly, perseverance and courage. “Rhizomes are root systems that grow horizontally in unpredictable directions without beginning or end. Rhizomes are always in-process, always growing, always adapting to form symbiotic relationships with existing forms of life. We are a self-organizing system; deeper than grassroots.”

“Rhizomes are root systems that grow horizontally in unpredictable directions without beginning or end. Rhizomes are always in-process, always growing, always adapting to form symbiotic relationships with existing forms of life. We are a self-organizing system; deeper than grassroots.”