Of the many divisive cases in U.S. legal history, few are as haunting as Korematsu v. United States (1944). In the ruling, the Supreme Court and Chief Justice Hugo Black argued that national security took precedence over individual liberties. And they maintained the legality of the infamous Executive Order 9066—which ordered the incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Of the many divisive cases in U.S. legal history, few are as haunting as Korematsu v. United States (1944). In the ruling, the Supreme Court and Chief Justice Hugo Black argued that national security took precedence over individual liberties. And they maintained the legality of the infamous Executive Order 9066—which ordered the incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans during World War II.

This decision has remained a stain on civil liberties ever since, and the June 26, 2018, Supreme Court’s reversal of Korematsu represents the first major victory since 1988 related to rectifying Japanese-American incarceration. However, by overruling Korematsu while approving President Donald Trump’s travel ban, the court has simply appropriated one tragedy to justify another. While Chief Justice John Roberts argued that President Donald Trump’s travel ban is legally different—and constitutional—in comparison to the Korematsu case, they both have the purpose of unjustly singling out individuals based on race. And although the subject of Japanese- American incarceration focuses on racial injustice towards U.S. citizens, it is also a story of immigration and how the U.S. government has employed racialized immigration policies under the vague guise of “national security.”

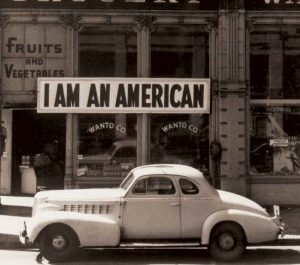

Even before camps like Manzanar existed for holding U.S. citizens of Japanese descent against their will, the FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service—the forerunner to ICE—had built their own camps to house Japanese citizens, often separating families in the process. Although Japanese immigrants had arrived in this country en masse since the 1870s, they were barred from naturalization. Long before U.S. involvement in World War II, the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover drafted extensive lists of so-called “disloyal enemy aliens” because of vague associations with Japan. While Germans and Italians were on this list as well, they numbered far less and always had the option to become U.S. citizens; Japanese immigrants would not share that opportunity until 1952.

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI conducted mass arrests of Japanese-American community leaders—sometimes in the middle of the night—and detained them in internment camps across the U.S. from Montana to Louisiana. Families often heard very little from their relatives in these camps, where their detainment lasted anywhere from a few months to several years. By 1943, the U.S. began a policy of deporting Japanese-Americans back to Japan as part of an exchange program with U.S. prisoners of war. On July 14, 1945, less than two months before the war’s end, President Harry Truman signed into effect a proclamation that permitted immigration officials to remove internees from the United States if they were deemed “a danger to the public peace.”

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI conducted mass arrests of Japanese-American community leaders—sometimes in the middle of the night—and detained them in internment camps across the U.S. from Montana to Louisiana. Families often heard very little from their relatives in these camps, where their detainment lasted anywhere from a few months to several years. By 1943, the U.S. began a policy of deporting Japanese-Americans back to Japan as part of an exchange program with U.S. prisoners of war. On July 14, 1945, less than two months before the war’s end, President Harry Truman signed into effect a proclamation that permitted immigration officials to remove internees from the United States if they were deemed “a danger to the public peace.”

One man who faced such a scenario was Katsuma Mukaeda.

In 1908, he immigrated from Japan to the United States. According to his 1995 obituary in the Los Angeles Times, he distinguished himself as a law student at USC and established himself as a successful lettuce grower in Southern California and a prominent figure in L.A.

Despite being unable to practice law because he was Japanese, he worked as a paralegal supporting the Japanese community. He was a champion for improving race relations within the greater Los Angeles community, and in 1935 helped establish the Society of Oriental Studies at The Claremont Colleges. According to scholar Malcolm Douglass, the society was founded with the intention of making the “Claremont Colleges the center of Oriental Culture on the Pacific Coast.” With help from a Rockefeller Grant, scholars at Pomona and Scripps worked alongside Mukaeda to established a strong emphasis on Asian Studies, and provided the foundation to the Asian Studies Library at Honnold-Mudd Library. To many, Mukaeda was an ideal U.S. citizen who advocated greater civic engagement and mending the issues of society.

Yet because of his activism, the FBI decided he was the perfect target. On Dec. 1, 1941, Hoover recommended Mukaeda’s internment “in the event of a national emergency.” Within a week after Pearl Harbor, FBI agents detained him with hundreds of other Japanese merchants, Buddhist priests and community leaders in the Los Angeles County Jail. Although no evidence of treason or sabotage was ever produced, Mukaeda was nonetheless interned for being “a suspect.” For years, he was shipped to various internment camps such as Camp Livingston, Louisiana, and Fort Missoula, Montana. By 1945, he found himself at Santa Fe Internment Camp, New Mexico, where a large number of internees were subjected to abuse by guards and sometimes received poorer treatment than enemy POWs in stateside camps. Following Truman’s proclamation, Mukaeda also found himself facing deportation back to Japan.

All the while, his family was separated from him. While Mukaeda was sent to one internment camp after another, his wife, Minoli, and son, Richard, were incarcerated at Poston Incarceration Camp in Arizona. When Minoli received word of the July 1945 deportation list that included her husband, she pleaded to the U.S. government and others for help, arguing that their only son “needs a father’s care now more than anything.” While researching Mukaeda’s FBI file at the National Archives as a part of my graduate studies in June, I found dozens of letters of recommendation and support written to FBI officials, all testifying to his loyalty and future importance of mending relations between Japan and the U.S. The letter writers—mostly long-term residents of the Los Angeles area—ranged from close friends to L.A. Times publisher Harry Chandler and former Pomona College President James Blaisdell.

For President Emeritus Blaisdell, the story of incarceration was clear throughout Southern California. Shortly after the arrest of Mukaeda and the passage of Executive Order 9066, thousands of Japanese-Americans were herded into so-called “assembly centers” at the nearby Los Angeles County Fairgrounds and Santa Anita Racetrack. Three students from Pomona were also forced to leave campus due to the executive order, and were famously given tearful goodbyes by their fellow classmates. While the College itself did what many other universities did at the time—provide students with transfer options to East Coast schools—Blaisdell went further to help out his friend.

Throughout the years of Mukaeda’s internment, Blaisdell wrote multiple letters to the FBI reaffirming both the activist’s loyalty to the U.S. and his importance to the Los Angeles community based on his previous work with Pomona and Scripps, the only Claremont Colleges at that time. Blaisdell’s first letter of May 17, 1944, was sent to help secure Mukaeda a second hearing by the FBI. When the hearing did not clear his name, Mukaeda went back to Blaisdell for help. In a letter to the FBI in November 1945, Blaisdell praised Mukaeda as “a man, I believe, who can be of great usefulness in healing the relations between the two countries and establishing just and honorable relations between the Japanese and Americans in this country.” After a reappraisal of his case, Mukaeda was deemed loyal and freed from the Santa Fe camp in February 1946, after four years in detention separated from his family.

Following the passage of the McCarran-Walter Act in 1952, Japanese nationals were finally able to become United States citizens. A final attestation of their friendship was a letter from Blaisdell to Mukaeda dated June 3, 1953, congratulating him on becoming a citizen and proclaiming,“I only hope that we who have been native born will be worthy of you.” Mukaeda continued to be a champion for the Japanese-American community until his death on November 8, 1995 at the age of 104.

There are two important lessons from Mukaeda’s story. One is that foreign policy dictated by racism and the violent separation of families are both, sadly, a recent chapter in U.S. history. Immigrants of all backgrounds have participated in the building of our nation’s history, and a system focused on exclusion only harms ourselves.

When Mukaeda was being held captive by immigration officials and on the brink of being deported, there were Americans who stood up for him. Pomona’s mission as a college—while constantly evolving—has always focused, in part, on the importance of social justice and activism. Often we think of these stories as being driven by powerful figures that leave everyday people as mere spectators; in reality we all can play a role. Mukaeda’s story, and Blaisdell’s tireless support, remind us of our constant duty to support those victimized by unjust laws or systems such as our current immigration system—and of the ability we have to effect change.

Jonathan van Harmelen ’17 is a graduate student at Georgetown University studying the comparative history of incarceration.