Winter Break Parties

20+ Years of Sagehen Spirit

Sagehens have been flocking to Winter Break Parties since at least 1994. In January, more than 700 alumni and guests braved winter weather in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle and Washington, D.C., to take part in the 2017 edition of this favorite tradition.

Frank Albinder ’80, host of this year’s party in D.C., offers Sagehen friends who could not attend a peek into a party:

Where was the reception held? “In the Billiards Room of a historic D.C. apartment building. A friend of mine lives there and arranges for us to use the space every year. I’d say there were about 50 of us this year.”

And there were snacks? “Oh yes. The reception was a Costco special—all your favorite snacks from a company founded by a Pomona alumnus. Everything from giant cheese wedges to giant cookies, giant bags of chocolate, giant chips and salsa, and other large-sized treats.”

A few favorite memories of the evening? “Hearing news from the Pomona campus was great. It was also fun to discover that a recent Pomona alumna had moved into the same building where we held the party just a couple weeks before the reception. I told her she’s in charge next year.”

To be sure you hear about Winter Break Parties and other Pomona events near you, update your contact information at pomona.edu/alumniupdate.

Countdown to Alumni Weekend 2017

Campus is buzzing with preparations to celebrate this year’s reunion classes (and welcome alumni of all classes back to Claremont) for the party of the year: Alumni Weekend, April 27-30, 2017. Online registration is open through April 15 at pomona.edu/alumniweekend and on site during Alumni Weekend. Don’t miss this chance to tour new buildings, enjoy a Coop shake on the Quad, attend lectures and performances, catch up with friends and professors and slap Cecil a high five.

Hundreds of Sagehens Rally in Support of DACA-mented and Undocumented Students

Since President Oxtoby published his “Statement in Support of the DACA Program and our Undocumented Immigrant Students” in November, hundreds of Sagehen alumni and families have reached out to the College to support Pomona’s own DACA-mented and undocumented students.

Here are two ways you can make a difference in the lives of these students right now:

- Make a contribution to the Student Emergency Grant Fund. Every dollar you donate goes directly to students who request funds, including students with emergency needs associated with immigration (immigration fees or legal resources, responding to family emergencies, etc.). To join the 296 members of the Pomona community who have supported this critical fund since November, visit pomona.edu/give and select “Student Emergency Grant Fund” from the designation menu.

- If you have legal expertise related to immigration, join the resource network of Pomona alumni who are offering pro-bono legal services to students with urgent immigration-related needs. The network, comprised of nearly three dozen alumni so far, is coordinated by Dean of Students Miriam Feldblum; Paula Gonzalez ’95, an immigration lawyer based in San Diego; and Derek Ishikawa ’01 of Hirschfeld Kraemer LLP, the College’s legal counsel, which is also providing pro-bono services related to this community effort. To join the network, email RSVPStudentAffairs@pomona.edu and include (1) your contact information and current company/organization information, (2) your legal specialty or focus and (3) your availability.

Happy 50th Birthday to Oldenborg!

Happy 50th Birthday to Oldenborg!

When Oldenborg Center was built in 1966, it was believed to be the first facility of its kind to combine a language center, international house and coeducational residence in a single building. And with air conditioning, its own dining hall, two-room singles or four-person suites and a great immersion-like environment for language majors, Borgies like Alfredo Romero ’91 remember it this way: “You never had to leave, even if you could find your way out.” Learn more about the history of Oldenborg at pomona.edu/timeline/1960s/1966 and celebrate this benchmark for the Borg by sharing favorite photos and memories at facebook/groups/Sagehens.

Travel/Study

Travel/Study

May 30-June 10, 2017

Burgundy: The Cradle of the Crusades

Join John Sutton Miner Professor of History and Professor of Classics Ken Wolf on a walking tour of Burgundy. Burgundy, the east-central region of France so well-known for its food and wine, was also an incubator for two of the most distinctive features of the European Middle Ages: monasticism and crusade. This trip provides the perfect context for exploring “holy violence” in the Middle Ages and its implications for the 21st century.

For more information, please contact the Office of Alumni and Parent Engagement at (909) 621-8110.

Are You a Fan of Sagehen Athletics? Why Not Become a Champion?

Are You a Fan of Sagehen Athletics? Why Not Become a Champion?

With scholar-athletes earning SCIAC honors, setting program records and competing in NCAA Championships—among many other achievements across teams—it’s a great year to be a fan of Sagehen Athletics! And right now, as Pomona and Pitzer colleges increase their investments in our athletics community, it’s a perfect time to become a Champion of Sagehen Athletics.

The Champions of Sagehen Athletics, formed earlier this year, is a group of supporters committed to changing the game for scholar-athletes by giving a gift that goes directly to the athletics program or any one of Pomona-Pitzer’s 21 varsity teams. Every gift has an immediate and profound effect in the lives of scholar-athletes and coaches, supporting team travel, upgraded facilities, equipment and apparel, and other tools and resources that allow Sagehens to thrive in the competitive world of NCAA Division III intercollegiate athletics. Learn more about this exciting moment in Sagehen history and become a Champion today at sagehens.com/champions.

ideas@Pomona LIVE RECAP: Climate Change & Cleantech Innovation Event

ideas@Pomona LIVE RECAP: Climate Change & Cleantech Innovation Event

On February 1, more than 30 Sagehens gathered at the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator (LACI) to think collectively and creatively about the challenges presented by climate change. A distinguished panel of alumni and faculty experts included Bowman Cutter, associate professor of economics at Pomona; Audrey Mayer ’94, associate professor at Michigan Technical University; Amanda Sabicer ’99, the evening’s host and vice president of Regional Energy Innovation Cluster at LACI; Matt Thompson ’96, president-elect of the Alumni Association Board; and Cameron Whiteman ’75, managing director at Vertum Partners. The Ideas@Pomona program curates the best content from around campus and the alumni community to ignite discussion, share ideas and highlight exciting areas of faculty research. Check out pomona.edu/lifelonglearning to find out more.

Professor Gary Smith Explains the Role of Chance in Everyday Life.

Professor Gary Smith Explains the Role of Chance in Everyday Life. Author/Professor Jonathan Lethem Discusses his Writing Process.

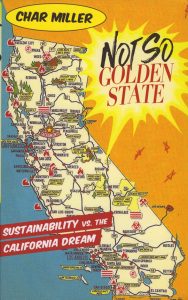

Author/Professor Jonathan Lethem Discusses his Writing Process. Professor Char Miller Looks Below the Surface of California’s Ecological History.

Professor Char Miller Looks Below the Surface of California’s Ecological History.