GRAB A STOOL at the old-fashioned lunch counter. Slip on a pair of earphones and press your palms to the hand outlines on the countertop. Close your eyes if you dare. A soothing Southern voice murmurs in your ear, “This your first time, right? So far, so good. You’ll be all right.” But then you hear the mob coming, surrounding you, jeering at you. “Git up!” A vicious jolt as if a ghost has kicked your stool. “If you don’t git up, boy, I’m gonna kill you.” The voice moves around you, so close you can almost feel the breath on your ear. Dishes shatter. Silverware jangles off walls. Sirens rise in the distance. Your stool is jostled again and again as the shouting engulfs you. “Kill him!” “Stomp his face!”

After 90 seconds, the chaos subsides, replaced by a woman’s voice: “What you’ve just experienced was created to honor the brave men and women who participated in the American civil rights sit-in movement.”

Heart racing, you lift your sweaty palms from the countertop and take away an indelible memory.

Which is exactly the way Tony Award-winning director, playwright and producer George C. Wolfe ’76 planned it.

George C. Wolfe ’76

IN 2006, THE CENTER for Civil and Human Rights consisted of three things: a collection of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s papers, on loan from Morehouse College; a parcel of land in downtown Atlanta, donated by Coca-Cola; and a dream—the dream of telling the story of the American civil rights movement to audiences too young to remember. The person responsible for making that dream a reality—the Center’s president, Doug Shipman—was looking for ideas, so he met with a lot of people, including Tom Bernstein, now chair of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

“Tom said, ‘You need a storyteller to be a central part of this. I think you need a non-traditional storyteller,’” Shipman recalls. “I said, ‘Who do you have in mind, Tom?’ He said, ‘George Wolfe.’”

At the time, Wolfe’s only apparent connection with museum design was a play he’d written two decades earlier, called The Colored Museum, in which 11 museum exhibits come to life on stage in scathing vignettes of the Black experience in America. But Shipman didn’t find Bernstein’s suggestion strange in the least. Today, museums like the Holocaust Museum aren’t just about collecting historical artifacts—they’re also about telling stories, recreating experiences, touching emotions—in other words, they’re a cross between a history class and interactive theatre.

For his part, Wolfe—who says if he hadn’t fallen in love with the theatre he probably would have been a history teacher—found the idea of playing a lead role in the conceptualization and design of the Center intriguing. He delayed saying yes, but within a few months, he was already starting to do what he always does when he takes on a new project—bury himself in research. After comparing notes, Shipman sent him a selection of books about Atlanta’s civil rights history. A couple of months later, when they met again, in addition to the books on Atlanta, Wolfe had gone through an additional 22. Shipman was startled both by the depth of detail that Wolfe had absorbed and by the completeness of his ideas.

“He drew this sketch,” Shipman recalls. “It was in a gallery format, how he wanted to tell the civil rights story. It had things like a shape that was a crescent moon—that was the March on Washington space. It had what he called then a game of ‘I’m sitting at a lunch counter.’ Almost all of the elements that you see here were in this drawing, and what was interesting to me was that he didn’t do it like an outline or a script. He did it in a space—he did it in rooms. That became the basis of what you see here. We pulled it out at the opening and we looked at it and we said, ‘I can’t believe it—look at that. That’s there. And look at that.’ It was incredible. His original vision was very, very clear.”

HAVING GROWN UP in the ’50s and ’60s in the partially segregated city of Frankfort, Kentucky, Wolfe describes his own memories of the civil rights movement as “visceral.”

“In 1964, Martin Luther King came to town for a march on Frankfort and my grandmother took me out of school so that I could march with her,” he recalls. “I also remember, very specifically the chair I was sitting in, watching TV as Robert Kennedy, standing atop a car, announced to a crowd in Indianapolis that King had been killed. These images and many others are vividly alive inside of me to this very day.”

For today’s young people, who don’t share that deep emotional connection to what was at stake, what was lost and what was won during the civil rights movement, Wolfe wanted to create a kind of immersion experience.

“I wanted to make sure that every single story we explored was not only grounded in a very specific intellectual rigor,” he says, “but I also wanted to find the entry point into each story, so that people with no overt connection to the American civil rights story, who are not walking around with a visceral minefield based on memories, and who didn’t march with their grandmother, could still make an emotional connection, could feel a similar kind of charge. That was the ambition that I set up for myself.”

The scale, he decided, shouldn’t feel grand and sweeping, but close and intimate—not like a film, but like a play.

“When you’re watching a film,” he explains, “you tend to lean back in your seat because the scale of what we are witnessing is so much larger than us. But when you’re watching a play and it’sreally working, you lean forward in the seat, because you’re recognizing that the bodies in peril on stage are the same as yours. That level of identification causes you to surrender.”

To keep the story on that level, he first had to decide how to weave in the colossal figure who towered over that civil rights landscape—Martin Luther King Jr. himself. Clearly, King was central to the story, and his unmistakably eloquent voice was its driving force, but Wolfe didn’t want him to dominate the narrative.

“There are people who come along and history makes them better than us,” he explains. “They start out like us, but history takes over and makes them better than us; our memories make them better than us; the circumstances of how they lived and died make them better than us. I didn’t want to create an homage to that. I wanted to create this—for lack of better words—celebratory journey of ordinary people, and how their sense of commitment and sacrifice and bravery changed the world.”

In his research, the stories that captivated him were some of the least known—like the story of Claudette Colvin, the teenager in Montgomery, Alabama, who refused to give up her seat nine months before Rosa Parks. But because of her youth and the fact that she was pregnant, it was decided by local civil rights leaders that she was not the right face for the moment, so the boycott didn’t begin until nine months later, when Parks became an icon of the movement. Or like the story of Ruby Bridges, the little girl who integrated New Orleans public schools and whose courage was immortalized by the Norman Rockwell painting that appeared on the cover of Look Magazine.

“Everybody can’t necessarily turn into Martin Luther King, but you can be a Claudette Colvin, or you can be a Ruby Bridges, or you can be a Viola Liuzzo. So the driving theme of the civil rights story became everybody can take a stand, should become invested in making their world a better place.”

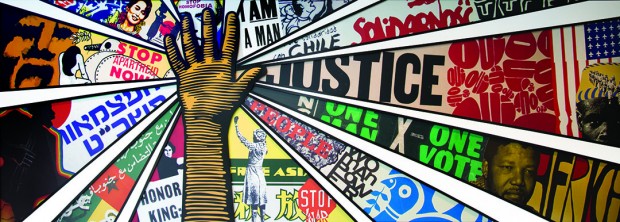

TODAY, THE CENTER is a shining, glass-fronted spaceship of a building occupying the northeast corner of Pemberton Place, a park that is also home to The World of Coca-Cola and the Atlanta Aquarium. In the lobby, your eyes are drawn to the giant mural that Wolfe commissioned from artist Paula Scher, depicting a range of human rights movements radiating out from an upraised, open hand.

To the left of the mural is a square portal with the words “Rolls Down Like Water: The American Civil Rights Movement” above the doorway. This is where most of Wolfe’s efforts were focused. The title comes from a King quote, printed to the right of the portal: “No, we are not satisfied and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Inside, Wolfe’s admittedly obsessive attention to storytelling detail is everywhere.

It’s in the burnt-out half-shell of a bus, papered over on the outside with mugshots of hundreds of Freedom Riders. Inside, you can sit on real bus seats and watch a documentary about their story.

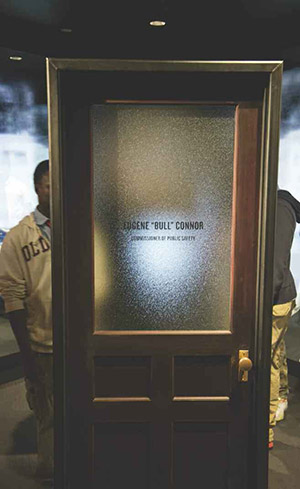

It’s in a free-standing office door in the middle of a room, with a frosted glass window bearing the name “Erotesters while Connor calmly defends the practice. (“I mean his title’s the commissioner of public safety,” Wolfe muses. “Can you get more ironic than that? ‘Hi, I’m the commissioner of public safety. Break out the hose and the dogs?’”)

It’s in four light-saturated, stained-glass windows hanging over a pile of rubble, honoring the four little girls killed in the Birmingham church bombing of ’63.

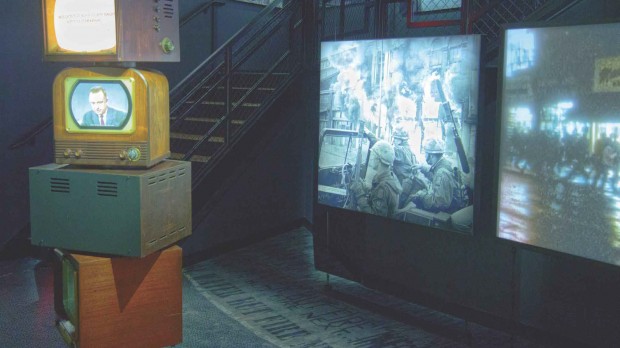

It’s in a stack of vintage television sets showing the breaking news of King’s assassination or the racist vitriol from Southern segregationists. (“I said, ‘Let’s find those ’50s and early ’60s TVs because to young kids they will look like pre-historic gadgetry, and they’ll initially enjoy the difference of it, and in turn be shocked by the horror of what they are seeing and hearing, so that hopefully they can begin to understand the journey we’ve gone on in this country.”)

But there’s more to Wolfe’s creation than just a series of self-contained exhibits. For Wolfe, it’s something more classical and more unified—a drama in three acts.

“The first act takes us up to just before the March on Washington,” he explains. “Then from the March on Washington and the four little girls and Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney, to LBJ and the political transformation—that’s the second act. And then, the last act begins with the assassination of King.”

The emotional power of it all is visible in a well-used box of tissues tucked into the corner of a couch in the upstairs room where footage of King’s funeral plays nonstop. “There were no tissue holders here,” Shipman says. “But literally we just put them there because we saw that people needed them.”

In addition to the emotional impact of the journey, however, Wolfe hopes visitors will come away with an appreciation for a couple of little-understood facts about the civil rights story.

One is that it was largely a youth movement.

“Delving into the research, and because I was a child when most of this was happening, it was startling to see how truly young everybody was,” he says. “To me this is part of why people are responding so emotionally; you’re constantly witnessing young faces risking their lives, sacrificing their youth if you will, to make a better world.”

The other is that these weren’t simply people caught up in the flow of history—each one of them chose individually to stand up and say no to injustice. He offers as an example the young people who took part in the lunch counter sit-ins, whose bravery was matched by their intentionality and thoughtfulness.

“I wanted people to begin to understand the deep level of mental, emotional and spiritual training these young people had to go through before participating in a sit-in,” he says. “The astonishing level of commitment that was required. I was also struck by how incredibly media-savvy the architects of the civil rights movement were. They knew that if you had these young black and white students, flawlessly dressed with their pressed shirts and ties, the women in gloves to match their outfits, sitting at a lunch counter, surrounded by these packs of uncouth hooligans, the cameras rolling, who’s going to come across as the normal human being whose cause is worthy, and who’s coming across as crazy?”

“PEOPLE SAY, ‘WELL, George C. Wolfe was involved, but was he really involved?” Shipman says after leading an early-morning tour of the exhibits. “I probably talked to George for seven years, two to three times a week, unless it was like, ‘Okay, for the next month I’m off the grid.’ But if we were working, we were talking about photo choices, script choices, positioning, everything. George had said early on, ‘I’m going to build this thing from the details up. Everything has to matter, and you’ve got to do it from the ground up.’”

As opening day approached, Wolfe’s focus became more and more intense. He reworked the sound for the lunch counter to maximize its emotional punch—right down to the volume of a breaking plate or the direction of sound for a thrown fork. He went through the exhibit with technicians, fine-tuning the sound at every station, obsessing over every detail.

“In theatre, I’m used to a preview period where daily you get to fix things based on the audiences’ response the night before, but we didn’t have that,” he says. “And so the lack of previews was making me crazy because I know from doing 9,000 shows that it’s easy to make a show go from okay to really good, but to make a play go from really good to brilliant, it’s a series of incremental improvements which ultimately elevate the material. So like I said, my obsession with detail got elevated to a crazed level, changing and fixing as much as I could for as long as I could.

Since the Center opened its doors in June, Shipman says the response has been overwhelming. “We get 15-year-olds who obviously weren’t there who say this is incredible. We get 80-year-olds. Yesterday the minister of culture for Ireland was here. She said, ‘This is just remarkable, the way you’re telling the story. It’s so relevant.’ I think that’s all a testament to George’s vision.”

For his part, Wolfe says he feels honored to play a role in the telling of such an important story. “I wanted to honor the people who stood up and said, ‘This is wrong!’ Who took a stance, changed the country, and in turn the world, and invented a vocabulary, a language of dissent that people the world over are still using to this very day. The Muslim women in Saudi Arabia, protesting the ban on woman drivers, dubbed themselves, ‘Freedom Riders.’”

But for a man who has devoted his life to the ephemeral art of the theatre, the most amazing part may be that the fruits of his labor haven’t already vanished. This is one set that will, for the foreseeable future, never be torn down. “I’ve been very fortunate to have worked on some really remarkable theatre projects, and I’m very proud of the work that I’ve done. But then the production ends and the work evaporates, because that’s theatre. People frequently stop me on the street and say, ‘Oh my God, when I saw Angels In America, or Bring In Da Noise, Bring In Da Funk—’ But that’s all that remains of those productions—memories. But when I go through ‘Rolls Down Like Water,’ and I watch people experiencing the exhibits, inside I’m screaming, ‘My God, I can’t believe it’s still here!’ The permanence of it all is very startling, and I’ve got to say there’s something about that I find wonderfully, naïvely reassuring.”