They don’t know it, but Pomona Economics Professor Gary Smith is the big-league ballplayers’ best friend in academia. That’s especially true for the superstars, the future hall of famers, the kind of guys who make the cover of Sports Illustrated. Truth is, the Joe Mauer crowd should be hoisting Smith on their shoulders and pouring champagne over his head. The professor has done them something better than clinch a pennant. He has added years to their very lives!

In his paper, “The Baseball Hall of Fame is Not the Kiss of Death,” Smith has debunked research that purported to show getting into Cooperstown would shorten a player’s life expectancy. He also has taken apart a study that suggested major league players with names that start with “D” die younger than others. (Derek Jeter really should send Smith a fruit basket.) Ditto for another piece of research that concluded players with negative initials (think ASS) die younger than players with positive initials (think ACE).

In his paper, “The Baseball Hall of Fame is Not the Kiss of Death,” Smith has debunked research that purported to show getting into Cooperstown would shorten a player’s life expectancy. He also has taken apart a study that suggested major league players with names that start with “D” die younger than others. (Derek Jeter really should send Smith a fruit basket.) Ditto for another piece of research that concluded players with negative initials (think ASS) die younger than players with positive initials (think ACE).

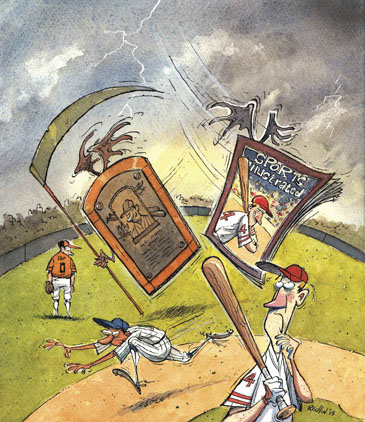

And what about the so-called Sports Illustrated cover curse? Smith offers a perfectly logical explanation for the phenomenon in which players who get on the cover see a drop-off in performance soon after—and it has nothing to do with a true deterioration in skills.

Smith, whose classes include economic statistics, draws on baseball because the sport offers such a large and well-defined body of data to work with. The problem, he says, is that tempting treasure trove of data also can be “ransacked” by researchers.

“You look at it enough, you’ll find patterns,” he says. “They just ransack the data and come up with something a little off and they come up with these ridiculous things.”

The methodological flaws Smith found in the aforementioned studies vary. In the case of the Hall of Fame research, the study drew upon a database of every known big league player, but in cases where there was no death date listed, researchers assumed the player was still alive (though, in reality, that was not always the case). The snag: For hall of famers, in contrast to lesser-known players, death dates are almost always known. That fact alone skewed the research.

Assessing the good/bad initials study, Smith found the results were invalidated by “selective inclusion of initials in a very small database.” As for the letter “D”-early demise research, Smith noted that the study was based on selective data, and that it didn’t hold up under a “valid test applied to more comprehensive data from the same source.”

If those studies were easy outs for Smith, the Sports Illustrated cover curse brings up the meatier statistical issue of regression to the mean. Simply put, you get on the cover at a time when you are doing your very best, and then “the only place to go is down,” explains Smith, the Fletcher Jones Professor of Economics.

“The fallacy is to conclude that the skills of good players and teams deteriorate,” Smith writes in his upcoming book, Duped By Data: How We Are Tricked Into Believing Things That Simply

Aren’t True. “The correct conclusion is that the best performers in any particular season generally aren’t as skillful as their lofty records suggest. Most had more good luck than bad, causing that season’s performance to be better than the season before and better than the season after—when their place at the top is taken by others.”

The misunderstood phenomenon of regression to the mean, writes Smith, is “one of the most fundamental sources of error in human judgment, producing fallacious reasoning in medicine,

education, government and, yes, even sports.”

Baseball is only one field of play for Smith’s research. The prolific professor has also taken on topics ranging from stock ticker symbols to poker players’ “hot hands” to measuring and

controlling shortfall risk in retirement. But with so much data available over so many years, the national pastime is one research realm he keeps going back to, even if he’s not big on watching the old ball game. “I’m more of a statistics fan,” Smith says.