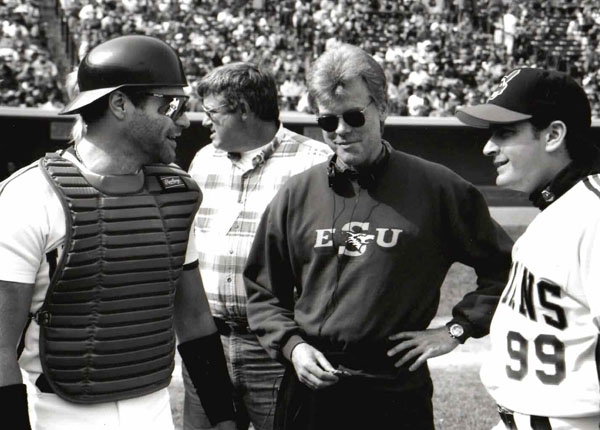

Director David S. Ward ’67, in center.

A great many things that seemed great in 1989 don’t seem especially so in 2013. Paula Abdul sent three songs to No. 1 that year, for starters, and there is also the matter of the miles upon unfortunate miles of acid-washed denim that were sold to people who had, at the time, no real reason to know better. So it is saying something about David S. Ward’s Major League that this 1989 film still feels fresh and, in some places, even oddly prescient today.

Yes, its double-knit uniforms look a little dated, and its stars are not nearly what they were 24 years ago—Charlie Sheen, the film’s comic center, is a mumbling, weirdly aggrieved advertisement for saying no to drugs; Corbin Bernsen, that era’s answer to George Clooney, now just seems a lot more like Corbin Bernsen. But Major League, somehow, is still Major League—a spectacularly quotable cult favorite still in heavy rotation on the endless bus rides of various minor league baseball teams and in the living rooms of baseball fans, and still one of the greatest and goofiest baseball movies ever made.

Both writer and director for Major League, Ward graduated from Pomona in 1967 and was a big-time Hollywood property not so very long afterward. His screenplay for 1973’s The Sting won him an Academy Award before he was 30 years old, and he has worked steadily and at his own pace since then. Steadily and very effectively—he was nominated for another Oscar for the screenplay to 1992’s Sleepless in Seattle, which he co-wrote with Nora Ephron and Jeff Arch, and has directed six films. The first of those was an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row. The second was a movie about a lousy Cleveland Indians team—built to fail by a cynical owner and comprised of misfits, flame-outs, broke-armed goofballs, ex-convicts with problems locating their pitches and Corbin Bernsens—that somehow gets itself together to make a pennant run. It’s the latter that still gets referenced on SportsCenter and among baseball fans.

“To this day,” Ward says, “I have people come up to me and quote lines from the movie that I’ve forgotten myself. There are these Major League trekkies out there, and it’s great. Every generation seems to discover it for itself.”

But the film that Major League newbies discover is not quite the same as the one that Ward made two and a half decades ago. It’s not that the movie is any less funny, or any less obviously a comedy—the slugger has a shrine to a demanding and arbitrary mini-deity named Jobu in his locker, the closer’s previous mound experience came in the California Penal League, and the jokes arrive with the regularity and pop of 95-mile-an-hour Clayton Kershaw fastballs. It’s just that, because Major League Baseball is so different, Major League seems different, too.

“When Major League came out, it was considered a broad comedy,” Ward says. “And I think it just seems less broad now.” Part of this is simply the game catching up to the movie. Ward had Sheen’s character, the control-challenged closer Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn, enter games from the bullpen to the strains of The Troggs’ “Wild Thing” as a sort of joke. “No pitcher came in to music, then,” Ward explains. “And then, after the movie, [Philadelphia Phillies reliever] Mitch Williams started coming into games to the same song.” Today, Ward’s “Wild Thing” gag barely even registers as such—in every ballpark at every level,

it seems every pitcher and hitter has his own walk-up music.

Even Major League’s central conceit—the intrinsic humor in a team built entirely around players who, for one reason or another, had no value to any other big league organization—is particularly fitting today. Teams like the Oakland Athletics and Tampa Bay Rays have built division winners by judiciously picking through and polishing players that other organizations left on the curb. “Because of the Moneyball approach, it seems more plausible that a team like this could win,” Ward said about the team of fictional misfits. “The Baltimore Orioles, to a certain extent, did it just last year.”

Ward grew up as an Indians fan in Ohio and Missouri, but moved west in his teens to Contra Costa County in the Bay Area, and later to Southern California. He brought his love of the Indians west with him, and while he downplayed his current fandom in our conversation, he quickly revealed that statement’s untruth, mourning Cleveland’s terrible luck—another aspect of Major League that hasn’t dated a bit—and assessing this year’s Indians team with a bullishness that reflected the benign chemical imbalance unique to fans.

While there are some obvious reasons why Major League has endured as it has—for starters: people like baseball and the jokes are good—Ward’s easy access to the wilder optimisms of the baseball fan brain is certainly a part of why the movie still works. The fantasy of a hopeless team finding some strange and sudden greatness is as old as the game itself, and utterly undated. “I just wanted to make an entertaining movie where the Indians actually won something,” Ward says.

He managed that, and more.