Lumberjacks, convicts, exiles, housewives, soldiers, sailors, concentration camp prisoners, Anna Karenina and the Ancient Egyptians all had bedbugs. The parasitic insects have pestered resters long enough for Americans to blame them on the British, for the Brits to blame them on the Americans, Asians and Africans, for cowboys to blame them on Indians, and vice versa. The Old World claimed bedbugs came from the New World, and the New World insisted they were brought over in boats from the old one.

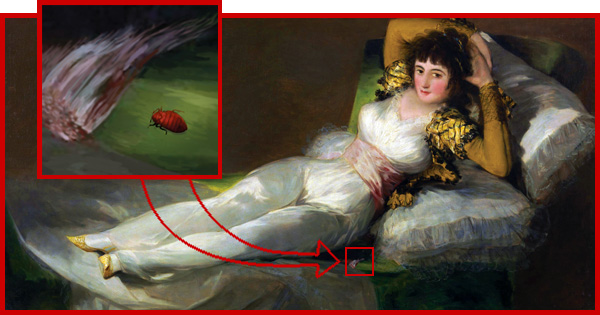

In their travels, bedbugs acquired countless nicknames: wallpaper flounder, nightrider, red rover, red coat, bed goblin and crimson rambler, to name a few, with many of the names referring to the color bedbugs turn when they have just fed and are full of blood. Hungry or newly hatched, the wee vampires are translucent, flat and colorless, deflated like a microscopic used condom. Their knack for biologically changing costumes inspired early victims to believe bedbugs had the power to magically transform themselves, the better to disappear into cracks and crevices and surprise their hosts.

People tried just about everything they could think of to get rid of bedbugs in the past. Mattress springs were “candled” with a candle or a blowtorch. Bodies were rubbed with tobacco, pepper or cedar leaves; beds were coated with sperm whale blubber, lard or whiskey. Pure mercury was poured straight into cracks in the floor, or kerosene was poured over the bed and injected into cracks and crevices around the bed (which significantly increased the number of house fires in America and England). So many dangerous poisons were used in houses and tenements infested with bedbugs that it was often impossible to tell if someone who died from overexposure to the remedies had been killed accidentally or on purpose.

![]()

The hard-to-kill bugs flourished in spite of it all, their populations increasing with the Industrial Revolution and the global shifts to cities that accompanied transoceanic travel. It wasn’t until the discovery of the insecticidal properties of DDT in the 1940s and its widespread use in the 1950s that the problem was largely (if only temporarily) eliminated in the majority of the United States. Paul Herman Muller, who made the discovery, was awarded the Nobel Prize because of DDT’s potential to control insect-spread diseases such as typhus and malaria on other parts of the planet.

In the 1960s, the publication of Rachel Carson’s landmark anti-pesticide manifesto Silent Spring catalyzed a paradigm shift in the way the world dealt with pests, beginning with the banning of DDT, continuing with exterminators slowly switching the tools of their trade to be less toxic and more local, and culminating with the green-friendly, chemical-free products many of us use to clean our homes today. This predominantly positive detoxification of the American home and environment has had one unanticipated side effect—it has created a loophole that bedbugs have been able to creep through, steadily multiply inside of and recently explode out of. Gone just long enough for us to be caught completely unawares by their comeback tour, bedbugs have proliferated enough to bring major infestations to New York and Toronto, and are rapidly spreading to other urban areas in the United States like bumps on a freshly-bitten victim.

Unfortunately, there is a personal reason for all of this research into bedbugs. Four years ago, when the parasitic insects invaded my home, fed off my flesh and infested my texts, I was working 60 hours a week in the New York office of Oxford University Press, editing online reference products that, not so long ago, were known as encyclopedias. I brought heavy boxes of manuscripts to happy hour after work in the evenings, and fell asleep in bed at night surrounded by the innards of some once-multivolume-soon-to-be-searchable-electronic-database, the corners of the tall piles of alphabetical entries forming jagged islands in my oasis of comforters and quilts.

The inkling that my private library had become a breeding ground for another species began with a series of small scarlet welts clustered around my wrists, neck and ankles. The arthropods living in my apartment were wingless and lazy, I would later learn, and thus attack areas on the body with the most pronounced veins. Once they have found one they will continue biting until their small bodies cannot hold a drop more, skulking slowly back to their hiding places amidst (in most cases) the seams of a mattress or (in my case) the pages of books, supposedly leaving rusty trails in the sheets after they arrive at their sixth and final life phase and have grown large enough to waste such precious food. “Breakfast, lunch and dinner” is the way this bite pattern is tagged in urban legend, the only legend in which my attackers were listed as I searched for confirmation of what was biting me from a more reputable source and found none.

![]()

Meanwhile, in the absence of an authoritative reference on bedbugs, I dredged the Internet hoping for clues on how to finally find one in my apartment and feel like I had earned the right to call an exterminator. The physician, dermatologist and, eventually, psychiatrist I’d consulted were convinced that my “chronic hives” were psychosomatic, and these professionals used their misinformation about bedbugs living only in old, dirty mattresses to advise me against what I later learned would have been the most reasonable, affordable and healthy thing to do. I should have contacted a reputable bedbug exterminator, if only for an inspection, which costs a mere $125. But I was convinced I had to find a bug before I called an exterminator, which is like waiting until you can actually feel a tumor before having a mammogram.

Alfred Barnard, the exterminator I later followed on his route around New York, would not be the first or the last person I spoke with to liken a bedbug infestation to cancer. Sanga, the exterminator who finally took care of my problem, and Lou Sorkin, the bedbug specialist at The American Museum of Natural History, agree that once the bugs have become big and dark enough to match the photos of them available online and pictured in newspapers as reputable as The New York Times, they have reached their final adult phase and are laying eggs all over the place, like a tumor left to metastasize.

Sanga was a delicate Trinidadian man with an accent that sounded British to my ears, aquiline features, two long French braids and a prison record he openly listed as one of the reasons he chose extermination as his profession. It didn’t matter to me however, after he came to my apartment and effectively gave me my nights and life back. After three months of constant searching for information, Sanga was the only person I’d talked to who had anything to say about bedbugs that made any sense or had any practical use.

As a thank-you gift, I offered to send Sanga any reference book he would like. He thought for a moment and then requested a famous book in his profession called Rodent Killer. He said it was a classic. He also said he wished there was such a tome about bedbugs, so that he could recommend it to his clients who bombarded him with more questions than he could answer as soon as he showed up at their door with his spray can.

It was then, and in the months that followed, that the idea and need for a print reference on bedbugs started to form in my mind. I wrote an essay about the epidemic in New York for Guernica Magazine, and, in the year since it was published, I’ve talked about five friends of friends per week, counseling them on what to do when they have bedbugs or other pests, how to insist their landlords operate within their legal obligations to exterminate, what to do when they refuse, and the answers to a million other questions fresh victims have when bitten by the foot soldiers of a global pandemic that keeps them up at night.

In 2010, The New York Daily News reported that one in 10 New Yorkers had dealt with bedbugs in their residence, and the number of bedbug complaints made by 311 callers in the Big Apple has increased from 537 in 2004 to more than 31,719 in 2010, according to the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. This year in Atlanta, the main pest control company, Orkin, reported a 300 percent increase in bedbug complaints in Florida and Georgia. The National Pest Management Association reports that Americans spent $258 million of their own money in 2010 to exterminate bedbugs, three times as much as in 2008.

However, contrary to what much of the sensationalist coverage of the epidemic would have you believe, the nationwide spread of bedbugs is not inevitable and bedbug victims are not doomed to an uncertain, unending future of sleepless, itchy nights. Most modern-day exterminators who specialize in bedbugs use a cocktail of three relatively safe chemicals that when correctly applied to a properly prepped home is effective in ending an infestation. The first two are pyrethrins and pyrethroids. Before the discovery of DDT as an insecticide, the most successful treatment for bedbugs was the use of a powdered form of pyrethrin and fumigation. Since the banning of DDT and other harsh chemical pesticides, pyrethrins, which are natural poisons made from the extracts of chrysanthemum flowers, and pyrethroids, which are synthetic replicas of those extracts, have come back into use.

![]()

The third ingredient in most bedbug specialists’ spray can is a brand name chemical called Gentrol, which exterminators often refer to as “the growth regulator.” Because bedbugs only eat warm human blood, it is very difficult to get them to consume enough pyrethrins and pyrethroids to kill them, which is a major characteristic that separates them from other pests like cockroaches that are comparatively easy to kill with baits and traps. Gentrol is crucial in controlling a bedbug population because it keeps them from reproducing. The founder of Zoëcon, the company that makes Gentrol and other hormonal insecticides that battle hard-to-poison insects by sterilizing them, is a scientist named Dr. Carl Djerassi. He is also one of the chemists credited with synthesizing the modern birth control pill.

Pesticide can be contraception as well as poison. In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson argued for a reactionary approach to pests as opposed to a preventative one, writing with extreme conviction that it was immoral to spray chemicals where we live. While quite reasonably and necessarily fighting for the protection of outdoor spaces (which at the time were being indiscriminately sprayed with DDT from airplanes without the consent of the people who lived in or near them so wantonly that public swimming pools had to be closed because of contamination), Carson neglected to discuss the use of relatively safe pesticides such as pyrethrins in urban environments such as New York City, where they are most needed and least likely to affect the harmony she prized so highly in the outdoors. To be clear, this is not in any way an attack on Carson, who is a heroine in my book, both literally and figuratively. Nor is it an argument for the return of DDT and other harsh chemicals in the United States. (Carson never argued against their use anywhere else, and her critics who say she is responsible for the spread of malaria in other parts of the world are overreaching.)

But my weekly conversations consulting friends of friends and other victims of bedbugs have turned me into something of an unlikely activist. Though cities such as New York have recently passed laws requiring landlords and building management companies to pay for the extermination of bedbugs, these laws are not enforced and so not followed. Landlords and building management companies must be forced to pay for safe and effective chemical extermination by trained professionals before bedbugs (and all pest problems, for that matter) reach a point at which a home or apartment becomes unlivable and the infestation begins spreading to neighbors.

We should know better by now. Insects that live primarily indoors, have very few natural predators, feed exclusively on humans, infest our belongings, spread rapidly and indiscriminately, are able to live for 18 months without food and can lay up to 500 eggs in a matter of weeks should be exterminated as swiftly and safely as possible. It is an investment that makes sense for anyone who is at all future-minded, not just the unfortunate souls whose sweet dreams bedbugs happen to be stealing in the present.