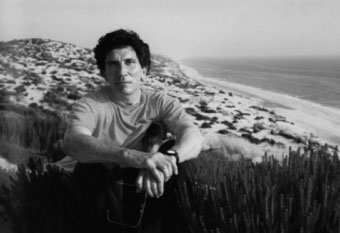

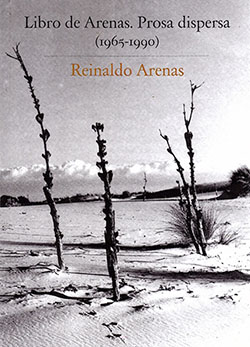

Pomona College Professor of Spanish Nivia Montenegro’s latest book, Libro De Arenas: Prosa Dispersa 1965-1990, is a compilation of the work of the late gay Cuban dissident writer Reinaldo Arenas, commemorating the importance of the literary and political figure known for his bestselling memoir Before Night Falls. For Montenegro, editing the book was an homage to the experience of fleeing one’s homeland, living as an exile and building a new life—an experience that is her own. Co-written with her husband Enrico Mario Santí, and researched with the help of Margaret Munts ’17, Libro De Arenas was recently published in Mexico and will soon be published in Spain.

Arenas—whose memoir was made into a film of the same name in 2000 starring Javier Bardem and directed by Julian Schnabel—left Cuba in 1980, where he had run into trouble for his writing, sexuality and politics and been imprisoned for his work. After coming to the U.S., Arenas became prolific, smuggling into the country past writing, rewriting from memory work that had been confiscated in Cuba, and contributing widely to newspapers and literary magazines.

Arenas—whose memoir was made into a film of the same name in 2000 starring Javier Bardem and directed by Julian Schnabel—left Cuba in 1980, where he had run into trouble for his writing, sexuality and politics and been imprisoned for his work. After coming to the U.S., Arenas became prolific, smuggling into the country past writing, rewriting from memory work that had been confiscated in Cuba, and contributing widely to newspapers and literary magazines.

“When people write about him, a lot of times they write about his gay nonconformist agenda…we wanted to bring out his other facets, like his political facets,” Montenegro says, noting his anti-Castro and anti-totalitarian critiques. “He was a whirlwind of activity and an activist before activism became a trend in the U.S.”

Montenegro became acquainted with Arenas’ work during her graduate studies, and in the book she describes reading Arenas as being “like walking along a gravel road, moving rapidly and refusing to stop because we may not be able to go any further. This urgency, the need to breathe deeply and consciously, permeates all of his prose, be it fiction, essay or journalism.” Munts, the student who transcribed Arenas’ papers for this book, calls his writing “incredibly heartfelt, incredibly profound and somewhat heartbreaking.”

Arenas’ writing cannot be understood in a vacuum. In Libro De Arenas, Montenegro writes, “To discuss the writings of Reinaldo Arenas means discussing his life.” It was a life not easily categorized, says Montenegro.

“He was a figure that for me fell through the gaps,” she says, not fitting into the Cuban exile community because of his sexuality and not fitting into the intellectual community because of his opposition to Castro. This was as the iconoclast writer preferred, Montenegro says. He refused to be classified by any one of those identities or conform to any one group, and Montenegro found his refusal to be pigeonholed brave.

Montenegro’s connection to Arenas’ writing runs deep because of her own story of leaving Cuba in 1968 as a teenager. She has sharp recollections of the fear and trauma the uncertainty and instability of the times exacted on her working-class family as they struggled for food and money, not knowing if they would be able to emigrate. She remembers the sound of planes flying low over Havana during the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, filling her with dread. When her family finally received a telegram that they were to leave in a couple of days, they were not allowed to take anything from their now-sealed home—not even a pen or photograph. By that time Montenegro, working in the countryside, felt she had aged far beyond her years.

Montenegro’s connection to Arenas’ writing runs deep because of her own story of leaving Cuba in 1968 as a teenager. She has sharp recollections of the fear and trauma the uncertainty and instability of the times exacted on her working-class family as they struggled for food and money, not knowing if they would be able to emigrate. She remembers the sound of planes flying low over Havana during the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, filling her with dread. When her family finally received a telegram that they were to leave in a couple of days, they were not allowed to take anything from their now-sealed home—not even a pen or photograph. By that time Montenegro, working in the countryside, felt she had aged far beyond her years.

“Everything inside [the house] was now out of reach, as if I had already traveled the 90 miles away from the island. I was 17 then but felt 30, if not older,” she says.

In her book, Montenegro writes, “Arenas’ sense of wonderment on leaving the island resonates loudly with me.”

Montenegro’s admiration for Arenas’ free-thinking and free-speaking ways and her sense of kinship with his work grew as she and Santí (professor of Hispanic studies at the University of Kentucky) met him and got to know him on a personal level. In 1990, stricken with AIDS, Arenas committed suicide. Culling through his papers at Princeton University was a way to honor his life.

“For me and for Professor Santí it was a labor of love not only professional. It was someone we knew whose life was incredibly difficult and very courageous,” she says.